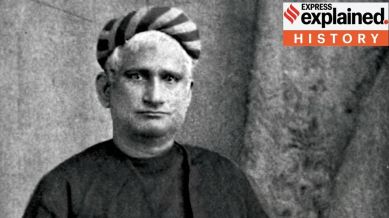

Vande Mataram 150 years: How Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay imagined nation as motherland in Ananda Math

Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay’s ‘Ananda Math’ was the first work of literature to frame the Indian nation as the motherland.

Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay’s Ananda Math (1882) is considered a foundational text for understanding Indian nationalism. His most influential idea was to imagine the nation as the motherland. “…The mother and the land of birth are higher than heaven. We think the land of birth to be no other than our mother herself…,” he wrote.

On Monday, speaking in Parliament on the 150th anniversary of Vande Mataram, a hymn published in Ananda Math, Prime Minister Narendra Modi repeatedly brought up this idea. “The freedom struggle was a struggle to free our motherland,” he said.

Imagining nation into existence

In his seminal book Imagined Communities (1983), Benedict Anderson demonstrated that nations were not the determinate products of given sociological conditions such as language or race or religion; rather, they had been imagined into existence. Partha Chatterjee, in The Nation and its Fragments (1993), refined this idea, specifically in the context of anticolonial nationalism, which, he said, divides “the world of social institutions and practices” into “the material and the spiritual”.

“The material is the domain of the ‘outside,’ of the economy and of state… [where] Western superiority had to be acknowledged and its accomplishments carefully studied and replicated,” he wrote. “The spiritual, on the other hand, is an ‘inner’ domain bearing the ‘essential’ marks of cultural identity. The greater one’s success in imitating Western skills in the material domain, therefore, the greater the need to preserve the distinctness of one’s spiritual culture.”

Ananda Math, written at a time when the British were consolidating their rule over the subcontinent and modern education was spurring nationalist ideas, does exactly that. Concerned about the loss of historical consciousness, Bankim mythologises specific events as a part of a larger project to reimagine the nation. As Sahitya Akademi Award-winning littérateur Meenakshi Mukerjee wrote in the paper ‘Anandamath: A Political Myth’ (1982): “The novel consolidated certain nebulous ideals and aspirations of a people who needed a new myth.”

Taking inspiration from history

Ananda Math is set in the backdrop of the 1769-73 Bengal famine, which killed 10 million people, and the late-18th century Sanyasi Rebellion, a series of armed uprisings against the rule of Mir Jafar and his East India Company overlords. Bankim reimagines the rebellion in nationalistic terms as a response to the injustices of Muslim rule and Company policy.

“Cowardly Mir Jafar, the heinous traitor, was unable to protect himself, how would he protect the lives and property of the people of Bengal? Mir Jafar drugged himself and dozed. The British extorted the revenue and wrote dispatches. The Bengalis merely wept and resigned themselves to their ruin,” Bankim wrote. In this context, a band of rebel sanyasis rose up to bring back the glory of the “motherland”, first through guerilla warfare and then in battle against Muslim and British forces.

Ananda Math thus marked a “constitutive moment in the gendering of national identity”, scholar Chandrima Chakraborty wrote in the paper ‘Reading Anandamath, Understanding Hindutva: Postcolonial Literatures and the Politics of Canonization’ (2006). “… [Bankim] constructs the trope of the ascetic nationalist, [and] lays down new criteria of social responsibility as filial duty to the nation.”

Bharat becomes Mata

Such a framing, Chatterjee wrote, emerged from the material-spiritual dichotomy in anticolonial nationalism. “The ‘world’ is a treacherous terrain of the pursuit of material interests, where practical considerations reign supreme. It is also typically the domain of the male. The ‘home’ in its essence must remain unaffected by the profane activities of the material world and woman is its representation. And so one gets an identification of social roles by gender to correspond with the separation of the social space into ghar and bahir.”

The filial duty Bankim put forth was of sons to their nurturing mother, long ravaged and shackled by foreign rule. Bankim forwarded an imagination of “disciplined, warlike, chauvinistic nation builders reared on a pedagogical apparatus of martial, scriptural and nationalistic values”. (Tanika Sarkar, Hindu Wife, Hindu Nation, 2013).

Bankim’s imagination was highly influential and Vande Mataram became a rallying cry for nationalists, especially during the Swadeshi Movement of 1905. Revolutionary Aurobindo Ghose would write in 1907: “…in a sudden moment of awakening from long delusions the people of Bengal looked round for the truth and in a fated moment somebody sang Bande Mataram. The mantra had been given…”