US researchers report promising development for male contraceptive pill: ‘Stopping sperm in its tracks’

Dr Jochen Buck and Dr Lonny Levin, professors of pharmacology at Weill Cornell Medicine, said the discovery could be a "game-changer" for contraception.

Researchers from Weill Cornell Medicine, US, have created an experimental contraceptive drug candidate that “temporarily stops sperm in their tracks and prevents pregnancies in preclinical models.” This means that a new kind of contraceptive for men, currently available through physical barriers (condoms) and surgical options (vasectomy), could be developed, similar to how a pill exists for women.

Dr Jochen Buck and Dr Lonny Levin, professors of pharmacology at Weill Cornell Medicine, said the discovery could be a “game-changer” for contraception. In the abstract for their study (‘On-demand male contraception via acute inhibition of soluble adenylyl cyclase’), published in Nature Communications on February 14, they wrote, “Nearly half of all pregnancies are unintended; thus, existing family planning options are inadequate.”

What does the study say?

According to the Weill Cornell Medicine Newsroom, the study came thanks to working on a single protein. “Dr Levin challenged Dr Buck to isolate an important cellular signalling protein called soluble adenylyl cyclase (sAC) that had long eluded biochemists,” it says. Later, the two began working together as part of a team.

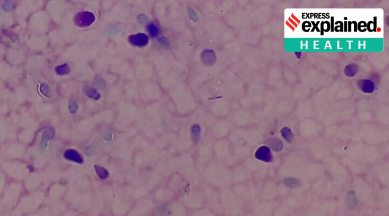

They discovered that mice genetically engineered to lack sAC are infertile. In 2018, Dr Melanie Balbach, a postdoctoral associate in their lab, discovered mice that were given a drug that inactivates sAC leads to sperms that cannot propel themselves forward. Therefore, sAC inhibition was seen as a possible safe contraceptive option as another team’s report stated men who lacked the gene encoding sAC were infertile but otherwise healthy.

How was the study done?

A single dose of an sAC inhibitor, called TDI-11861, was found to immobilise mice sperm for up to two and half hours, and effects persist in the female reproductive tract after mating. After three hours, some sperm begin regaining motility; by 24 hours, nearly all sperm have recovered normal movement.

“Our inhibitor works within 30 minutes to an hour,” Dr Balbach said. “Every other experimental hormonal or nonhormonal male contraceptive takes weeks to bring sperm count down or render them unable to fertilize eggs.”

The team now plans on conducting these experiments in a different preclinical model, eventually hoping to progress to human clinical trials.

Why has the male contraceptive pill been difficult to develop?

Contraception, in general, has been focused on women. In 1960, the oral contraceptive pill was approved for release. Although the pill has also not been completely uncontroversial, often resulting in side-effects such as the risk of blood clots developing and even a risk of cancer according to some studies, there was also a great benefit. It allowed women to have more agency in child-bearing.

How the pill worked was through regulation of the hormones progestin and estrogen, preventing fertilization of the egg by the sperm. Christina Wang, a contraceptives researcher in the US, told The Washington Post that biology may be at play for why the same has not happened for men. Women produce one egg per month while men produce sperm in much larger numbers. Hence, developing a method is more challenging.

At times, studies have been abandoned after finding even slightly mild side effects, such as acne or mood swings in a 2016 study, even as women have dealt with these over the years. But that also has to do with changing norms on what is now acceptable in such trials, as compared to when women’s contraception was being developed in Western countries in the middle of the 20th century.