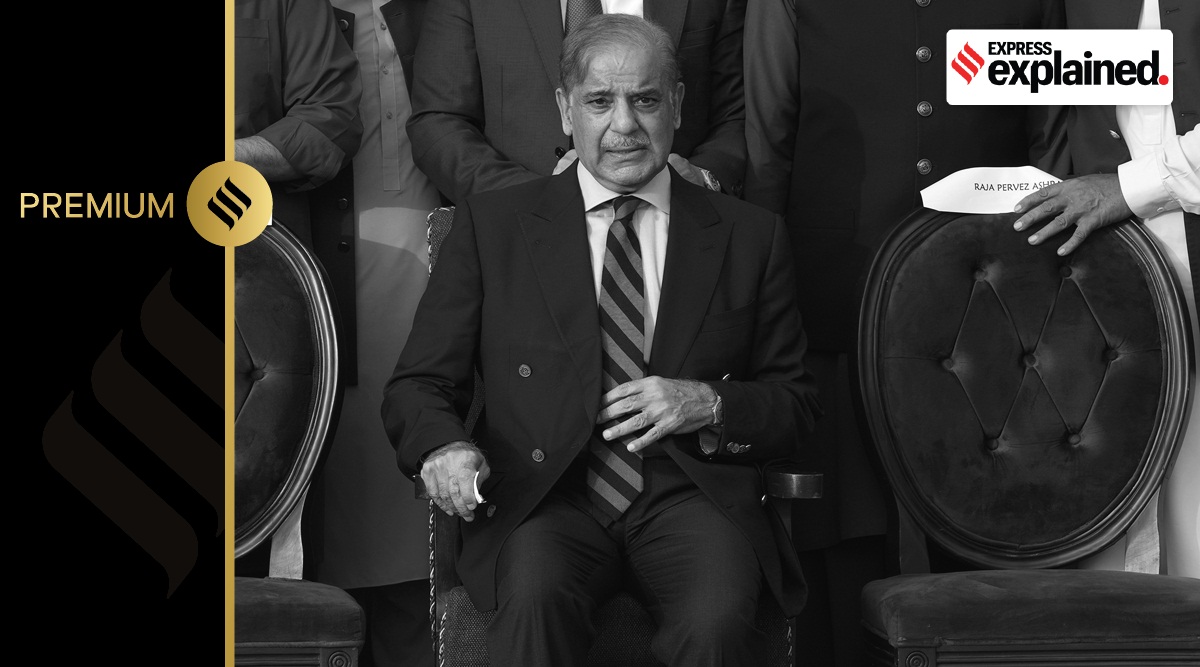

Pakistan Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif’s 16-month tenure came to an end on Wednesday (August 9), after he advised the “dissolution” of Pakistan’s lower house of parliament. President Arif Alvi dissolved the National Assembly three days before the completion of its five-year tenure.

Sharif will continue to discharge the PM’s duties till a caretaker Prime Minister is decided upon. In Pakistan’s system, a caretaker government takes charge in the interim period so that free and fair elections can take place. Officially, elections should be conducted within 90 days of the dissolution of parliament.

The fate of the elections, however, is at stake, because of the turn of events surrounding Imran Khan. And, the powerful Pakistan Army — the saying goes that most countries have an army, but Pakistan’s army has a country — holds the cards and is the kingmaker.

After then-PM Imran was removed from office by a no-confidence motion in April last year, he was convicted and sentenced by a trial court on August 5 in what is called the Toshakhana case. The case revolves around what is seen as “dishonest behaviour”, as he failed to disclose the specifics of the Toshakhana presents (gifts received by him as Prime Minister) in his annual declaration of assets to the Election Commission of Pakistan.

But his fall from grace began in May this year, when he was convicted of corruption and his protesting supporters ransacked some military installations, including a senior Pakistan Army officer’s home. The Pakistan Army did not take kindly to the damage to their perception of invincibility, and termed May 9 as “Black Day”.

After that, the Army went after Imran Khan’s party, PTI. PTI leaders and supporters were arrested, and within days, the party was crippled. Many leaders overnight changed their stance, deserting their party and their affiliation — in Pakistan’s local parlance, they underwent “software updates”. Pakistan’s establishment managed to wean away top leaders of the party and formed what is called a “king’s party”, Istehkam-e-Pakistan.

PTI is now being led by former Pakistan Foreign minister Shah Mahmood Qureshi, who is the vice-chairman of the party. Many PTI leaders who didn’t change their affiliation are either in jail, have fled, or have gone underground.

Story continues below this ad

Imran now has about 200 cases against him from treason to corruption, and has only been able to speak to some foreign media. Pakistan’s media has been banned by the Pakistan Electronic Media Regulatory Authority from broadcasting his speeches and press conferences, on the grounds that he is promoting hate speech and attacking state institutions. Top Pakistan journalists have said they can report on the charges and cases against Imran, but can’t mention his name or show his pictures.

Imran’s conviction in May and now in August disqualifies him from holding any public office or contesting elections for the next five years. While he can appeal in the higher courts and the supreme court, the process is the punishment.

Imran’s reversal in fortunes is almost a replay of how his predecessor and Pakistan’s veteran politician Nawaz Sharif was disqualified in a corruption case in 2017. What is common in their cases is that they both fell out of favour of Pakistan’s establishment — the Pakistan Army and its security apparatus.

When Imran came to power after the 2018 elections, it was alleged that the Army had rigged the polls in his favour, and the Opposition always said the PTI leader was “selected” and not elected.

Story continues below this ad

Now, the wheels have turned, as last year, Sharif’s younger brother Shehbaz Sharif was tapped by the Army as the consensus candidate to replace Imran and lead the country.

Pakistan’s analysts have called both Imran’s and Sharif’s governments “hybrid” regimes — essentially a mix of civilian and military power structure, where the remote-control lies with the generals in GHQ in Rawalpindi.

This is where the caretaker government and the fate of elections become important.

The caretaker government, which was introduced by former Pakistan President and dictator General Zia ul Haq in 1985, is mandated to carry out day-to-day affairs of governance. According to Pakistan’s laws, the caretaker government is expected to restrict itself to activities that are “routine, non-controversial and urgent”. Its decisions must be in “public interest” and “reversible” by the future government elected.

Story continues below this ad

But, in the run-up to the dissolution of parliament this time, two significant developments have taken place.

First, a digital census of 2023 was approved in haste by a constitutional body called the “Council of Interests”, consisting of the Pakistan PM, four Chief ministers of Pakistan’s provinces, and three members nominated by the PM (usually cabinet ministers). This puts Pakistan’s population to be 24 crore, up from 21 crore in the 2017 census. Now, the law mandates that there should be delimitation before the next elections, and that process would officially take 120 days.

The second development was the empowering of the caretaker government, which now has powers to take far-reaching decisions beyond day-to-day affairs. This is a result of a series of legislations — more than 100 since July 1.

The legislative changes allow Pakistan’s caretaker government to handle everything from foreign investments to military takeover of natural resources to infrastructure (water, power), give sweeping powers to security agencies, and reduce civil liberties and freedom of expression.

Story continues below this ad

The Sharif-Bhutto Zardari regime is believed to have acted in sync with what the Pakistan’s establishment wants, under the rationale that the caretaker government needs to take decisions amid the economic situation in the country — it just got its 24th IMF intervention of USD 3 billion.

The caretaker government has traditionally been filled in by Pakistan Army’s choices — although on paper, they are chosen by the Prime Minister and the Leader of Opposition (the political leadership), and, if there is no consensus, the Election Commission.

This time, the names doing the rounds include that of Jalal Abbas Jilani, who was Pakistan’s foreign secretary in 2012-2013. A relative of former Pakistan PM Yousaf Raza Gilani from PPP (Bhutto Zardari’s party), Jilani also worked with Nawaz Sharif. He went on to become Pakistan’s ambassador to the US, a job reserved for the Pakistan establishment’s candidate.

The empowering of the caretaker government and the census that would entail delimitation signal that the election can be deferred — Pakistan’s analysts estimate it could be around February-March 2024 or even later.

Story continues below this ad

The civil society in Pakistan is concerned at this turn of events, and views this as a possible takeover by the Army — ruling by proxy through civilians.

For New Delhi, the delay in the holding of polls could mean that both the countries have similar election cycles in 2024. And, by the end of 2024-early 2025, the US too will go to polls. With leaders in Delhi, Islamabad and Washington DC being elected within a year’s time frame, a window of opportunity opens up for concrete and meaningful engagement between India and Pakistan — without a major political cost.

But realistically speaking, the establishment in both Delhi and Islamabad — read Rawalpindi and Army chief Asim Munir, — has to see if there is any value in engaging with each other. For now, Pakistan has to first put its house in order. The irony of a former PM in Pakistan being arrested and jailed on August 5 — the day Article 370 was abrogated — is not lost on anyone.