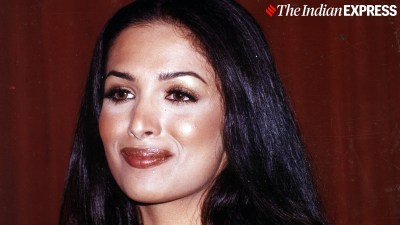

Nobel Peace Prize 2025 winner: Maria Corina Machado, ‘Iron Lady’ of Venezuela

Maria Corina Machado, Nobel Peace Prize 2025: Machado has long been one of the strongest advocates for democracy in the country that has long been under a repressive dictatorship.

Opposition leader Maria Corina Machado greets supporters in Guanare, Venezuela, on July 17, 2024. Barred from running for president herself, Machado helped galvanise support behind the candidate challenging President Nicolas Maduro in elections. (Adriana Loureiro Fernandez/The New York Times)

Opposition leader Maria Corina Machado greets supporters in Guanare, Venezuela, on July 17, 2024. Barred from running for president herself, Machado helped galvanise support behind the candidate challenging President Nicolas Maduro in elections. (Adriana Loureiro Fernandez/The New York Times)Nobel Peace Prize 2025: The Nobel Peace Prize was awarded on Friday (October 10) to Maria Corina Machado, a Venezuelan politician who has for decades fought for democracy and civil liberties in the Latin American country.

“As the leader of the democracy movement in Venezuela, Maria Corina Machado is one of the most extraordinary examples of civilian courage in Latin America in recent times,” the Norwegian Nobel Committee’s announcement stated.

Dictatorship in Venezuela

To understand why the Nobel Committee felicitated Machado one must first look at the decline of Venezuela’s democratic institutions over the past three decades.

Until the 1990s, Venezuela had one of the longest-running democracies in Latin America; today it is one of the region’s most entrenched authoritarian regimes. Political scientist Laura Gamboa in her paper ‘Plebiscitary Override in Venezuela: Erosion of Democracy and Deepening Authoritarianism’ (2025), chronicled how this happened under the regimes of Hugo Chávez, and now Nicolás Maduro.

The erosion began in 1999, when Chávez, then newly elected as President with massive popular support, convened a constitutional assembly to draft a new constitution for Venezuela without the approval of the legislature.

What made things worse was that the anti-Chavista coalition, despite a significant presence within democratic institutions including the National Congress and the media, chose to support a (failed) coup in 2002 (backed by the US) and then an oil strike, in order to get Chávez to resign. This gave Chávez, still enjoying popular support in the streets, justification to go on a Stalinist purge across all institutions.

“Using tactics like coups, boycotts or strikes can be effective ways to protest a government, but they can backfire when you leverage them against a popular and democratically elected president,” Gamboa wrote.

By 2006, the anti-Chavista coalition had lost most of the institutional resources. Over the next two decades, Chávez, and then Maduro, since 2013, have strengthened their grip over Venezuela, despite mounting international pressure.

The 2024 elections, which Maduro claims to have won, is widely recognised by international players to have been heavily rigged: it occurred amid heavy repression of Maduro’s opponents, including Machado, who was disqualified from contesting, and the results were allegedly manipulated to undermine the popular mandate against the incumbent Maduro.

Years of dictatorship, economic mismanagement, and international sanctions have not only eroded Venezuela’s democracy but also the popularity of the socialists, who came to power with the promise of making things better for the average citizen. Venezuela has the largest oil reserves in the world, but the fruits of this mineral wealth has been disproportionately concentrated at the top, among Maduro and his die-hard loyalists.

‘Ballots over bullets’

Over the past two decades, Machado has emerged as one the staunchest opponents of Maduro, at the helm of the fight for “a just and peaceful transition from dictatorship to democracy”, the Nobel Committee said.

Born in Caracas in 1967, Machado comes from privilege: her father was a steel magnate with ties to some of South America’s most famous historical figures, including Simón Bolívar, who led what are now the countries of Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador, Peru, Panama, and Bolivia to independence from the Spanish Empire.

Machado has a bachelor’s degree in industrial engineering and a master’s degree in finance. In 1992, she established the Atenea Foundation, which works to benefit street children in Caracas. A decade later, she found Súmate, a volunteer organisation whose primary task is to monitor elections.

In a 2004 profile published in The Washington Post, Machado described how she decided to establish Súmate.

“Something clicked. I had this unsettling feeling that I could not stay at home and watch the country get polarized and collapse… We had to keep the electoral process but change the course, to give Venezuelans the chance to count ourselves, to dissipate tensions before they built up. It was a choice of ballots over bullets.”

In 2003, Súmate organised a campaign to force a recall referendum. Article 72 of Venezuela’s constitution allows for a referendum to “revoke” the mandate of the president provided he has already served half of the term and “at least 20% of voters registered” extend a petition calling for a recall referendum.

The referendum was held in 2004; Chávez held on to power although there were allegations of massive voter fraud, including by Súmate. Chávez branded the leaders of Súmate as “conspirators” and “lackeys of the US government”, and slapped a number of criminal charges. Machado was charged with treason and conspiracy, under Article 132 of the Venezuelan Penal Code.

This triggered an outpouring of support for her from around the world, even as Venezuelans themselves were deeply divided over her actions. A 2005 profile by The New York Times said: “In a highly polarized country, María Corina Machado has emerged as perhaps the most divisive figure after Mr. Chávez…”.

From election watchdog to popular politician

Machado’s overt ties with Washington, which she herself has never denied, are one reason for her divisive stature in Venezuela. In 2005, after being accused of treason in her home country, she received an invite to the White House from then President George Bush Jr.

Súmate has also received generous funding from American donors, most notably, the Washington-based National Endowment for Democracy, which, according to its website, “makes more than 2,000 grants to support the projects of nongovernmental groups abroad who are working for democratic goals in more than 100 countries”.

But Machado had always maintained that her opposition to Chávez was not due to their ideology but their efforts to undermine democracy, casting her role as an “electoral watchdog”, more than anything else.

Maria Corina Machado, March 24, 2024. The New York Times

Maria Corina Machado, March 24, 2024. The New York Times

“The idea was not, how do we get rid of this government,” Machado told The NYT in 2005. “The idea was how do we resolve the profound social differences… Our organization seeks to preserve citizens’ rights, and the way to do that is by exercising those rights.”

But as the regime in Caracas became increasingly more autocratic, Machado too has become more active politically. By the late 2000s, Machado emerged as the leader of the opposition’s Coalition for Democratic Unity (MUD). By 2010, she declared her candidacy for the 2012 Venezuelan presidential election. Chávez, notably, welcomed her candidacy. “Ah, how I would like to face that little bourgeois lady in 2012… It would be the ideal battle,” Chávez said in a press conference after the MUD gave his Unified Socialist Party of Venezuela (PSUV) a run for its money in the 2010 legislative elections.

The battle, however, never took place: Machado lost to fellow anti-Chavista Henrique Capriles in the primary. Capriles would later lose to Chávez in 2012, and a year later, to Maduro after Chávez’s sudden death.

‘Iron Lady’ against Maduro

Since 2013, Machado has been at the forefront of many anti-government protests against Maduro. And she has paid a price for her opposition, from facing criminal charges to intimidation and even the threat of physical violence by Maduro’s allies.

As many of her anti-Maduro politicians, including Juan Guaidó, have fled from the country, Machado has remained with her people, vocally fighting for her rights. (Guaidó was a key figure in the 2019-23 Venezuelan presidential crisis; Trump, in his previous term, had declared the young legislator as the president after alleging electoral fraud by Maduro.)

And as someone who has remained, in keeping with her popular refrain of “hasta el final” (“till the very end”), Machado has successfully corralled much of the previously divided opposition behind her.

“María Corina’s movement revolves around the people’s weariness with Madurismo,” Andrés Izarra, a political analyst, told The NYT in 2024.

Under Maduro, Venezuela has witnessed an extraordinary economic contraction — the largest outside of war in at least 50 years, economists say, according to The NYT. Millions of people are still struggling to meet daily ends, and are frustrated with the rampant corruption and misgovernance.

In this backdrop, Machado in 2024 mounted what she herself claimed was the strongest opposition campaign in the past 25 years. “Never in 25 years have we gone into an election in such a strong position,” she had said.

While she was barred from contesting herself, it was her, and not the little known former diplomat Edmundo González, that the people were voting for.

While her campaign failed to oust Maduro, its resonance among the people, some argue, are ushering in winds of change. As the Nobel Committee put it: “Despite the risk of harassment, arrest and torture, citizens across the country held watch over the polling stations. They made sure the final tallies were documented before the regime could destroy ballots and lie about the outcome.

The efforts of the collective opposition, both before and during the election, were innovative and brave, peaceful and democratic. The opposition received international support when its leaders publicised the vote counts that had been collected from the country’s election districts, showing that the opposition had won by a clear margin.”

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05