When, in May 2016, India adopted inflation targeting as a policy goal enshrined in law, it also embraced the idea of central bank “independence with accountability”. Under the new statutory framework, the central government would, in consultation with the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), set an inflation target based on the consumer price index (CPI) once every five years. The RBI was entrusted with the responsibility of meeting this target (“accountability”), for which it would be given “independence” in the conduct of monetary policy.

But in the situation that the economy today is in, the RBI is struggling to be accountable and, at the same time, having to increasingly depend on the government for fulfilling its mandate.

Failure of accountability

Take accountability, to begin with.

The Centre, under section 45ZA of the RBI Act, 1934, has fixed the CPI inflation target at 4% with an “upper tolerance limit” of 6%. However, actual year-on-year inflation in 2022 has ruled above 6% every single month from January to August. If it does so in September as well, the RBI, under section 45ZN of the same law, will have to submit a report to the Centre on “the reasons for failure to achieve the inflation target” and “remedial actions proposed to be taken by the Bank”. In this case, “failure” is defined as inflation being more than the upper tolerance level of the target “for any three consecutive quarters”.

Accountability has been a relatively new problem though.

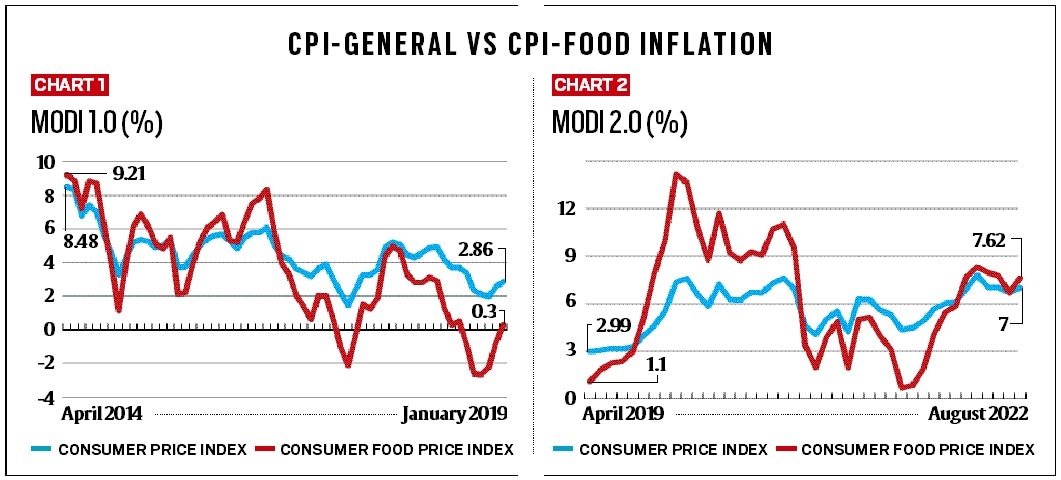

During the Narendra Modi government’s first term, roughly from April 2014 to March 2019 (Modi 1.0), CPI inflation was above 6% only in 6 out of 60 months. Moreover, 5 of those 6 months were in 2014, well before the RBI Act was amended to provide a statutory basis for inflation targeting.

Overshooting of the inflation target has been more during the Modi government’s second term (Modi 2.0). In the 41 months from April 2019, inflation has exceeded 6% in as many as 21. In other words, a failure rate of over 50%, as against 10% during Modi 1.0. Also, average CPI inflation was 4.5% during Modi 1.0, whereas it has been 5.7% so far in Modi 2.0.

But in the situation that the economy today is in, the RBI is struggling to be accountable and, at the same time, having to increasingly depend on the government for fulfilling its mandate.

But in the situation that the economy today is in, the RBI is struggling to be accountable and, at the same time, having to increasingly depend on the government for fulfilling its mandate.

Reason for this situation

There’s a simple reason for the RBI’s “failure” to adhere to its inflation-targeting mandate. It has to do with food and beverage items, which have a combined 45.86% weight in the overall CPI. The accompanying charts show year-on-year increases in the general CPI as well as the consumer food price index (CFPI), both during Modi 1.0 and Modi 2.0.

Story continues below this ad

During Modi 1.0, food inflation was lower than general inflation in 38 out of the 60 months, with the former averaging just 3.5%. Thus, while inflation overall was benign (average of 4.5%), food inflation was even more so. It has been quite the other way round during Modi 2.0, with average CFPI inflation, at 6.3%, more than the 5.7% for general inflation. Also, food inflation has been lower than CPI inflation in only 21 out of 41 months. While CPI inflation has risen and overshot the 6% target, especially in recent months, the acceleration has been all the more for food inflation since late-2021. The latter has also tended to exhibit greater volatility during Modi 2.0, which is clear from the charts.

Simply put, both the “success” of inflation targeting in Modi 1.0 and “failure” in Modi 2.0 has been largely courtesy of food prices.

Monetary dependence

That links up to the second issue of monetary policy independence — which basically refers to the central bank being insulated from government interference or electoral pressure in setting its interest rates with a view to achieving low and stable inflation.

But therein lies the irony: The preponderant weight of food tems in the Indian consumption basket and hence its CPI — in contrast to developed countries where their shares are hardly 10-25% — makes inflation that much less amenable to control through repo interest rate or cash reserve ratio hikes. The RBI, then, is forced to rely more on government action to meet inflation targets. Far from acting independently — using monetary policy tools that seek to curb demand by raising borrowing costs for firms and consumers — it has to depend on “supply-side” measures by the government. That translates into monetary dependence, not independence.

Story continues below this ad

To get an idea of the government’s supply-side actions that have made the RBI’s job easier, consider the following:

In the last one year, the effective import duty on crude and refined palm oil has come down from 30.25% and 41.25% to 5.5% and 13.75%, respectively. It’s been even sharper — from 30.25% to nil — for crude soyabean and sunflower oil.

On May 13, this year, the Modi government banned exports of wheat. This was extended to wheat flour — including atta, maida and rava/ sooji (semolina) — on August 27.

On September 8, exports of broken rice were prohibited. Besides, a 20% duty was imposed on shipments of all other non-parboiled non-basmati rice.

Story continues below this ad

On May 24, sugar exports were moved from the “free” to “restricted” category. Further, total exports for the 2021-22 sugar year (October-September) were capped at 10 million tonnes, which was raised to 11.2 million tonnes on August 1. The export quota for the next sugar year is yet to be announced.

On August 12, the Centre directed states and union territories to force pulses traders/millers to declare their stocks of tur (pigeon-pea) and upload this information on a weekly basis.

Implications of this

The framework of inflation targeting and central bank “independence with accountability” worked well during Modi 1.0. That period was characterised by benign food (and fuel) prices, both domestic and globally. The RBI could, therefore, act in almost splendid isolation and pursue its goal of price stability without being constrained by government intervention or even fiscal policy.

Things have been different in Modi 2.0. The last two years or less have seen a resurgence of inflation, driven mainly by supply-side factors — from the pandemic and the war in Ukraine to extreme weather events. The last includes excess rain during September-January 2021-22, the heat wave in March-April and the deficient monsoon in the Gangetic plain states this time.

Story continues below this ad

Newsletter | Click to get the day’s best explainers in your inbox

These — along with skyrocketing prices of fuel, which have a 6.84% weight in the CPI, over and above the 45.86% of food — have rendered the RBI’s demand-side toolkit to fight inflation ineffective.

Wanting to be left alone is one thing. But this is a battle the central bank cannot win without the government.

But in the situation that the economy today is in, the RBI is struggling to be accountable and, at the same time, having to increasingly depend on the government for fulfilling its mandate.

But in the situation that the economy today is in, the RBI is struggling to be accountable and, at the same time, having to increasingly depend on the government for fulfilling its mandate.