For Ajay Kumar Singh, a farmer from Emiliya village in Chandauli district of eastern Uttar Pradesh, the showers in September have been “amrit sanjeevani”, a potion giving new lease of life to his paddy plants that had nearly dried up.

It’s been the same for Raju Borkhatariya, a groundnut grower from Matiana village in Gujarat’s Junagadh district, who calls the southwest monsoon’s revival this month “kachu sona” or raw gold from heaven.

Both weathered an extended dry spell in August, through which they kept their crop alive by pumping out groundwater. The majority of Indian farmers though, with no tubewell or canal water irrigation access, would have simply seen their crop wilt.

Irregular rain

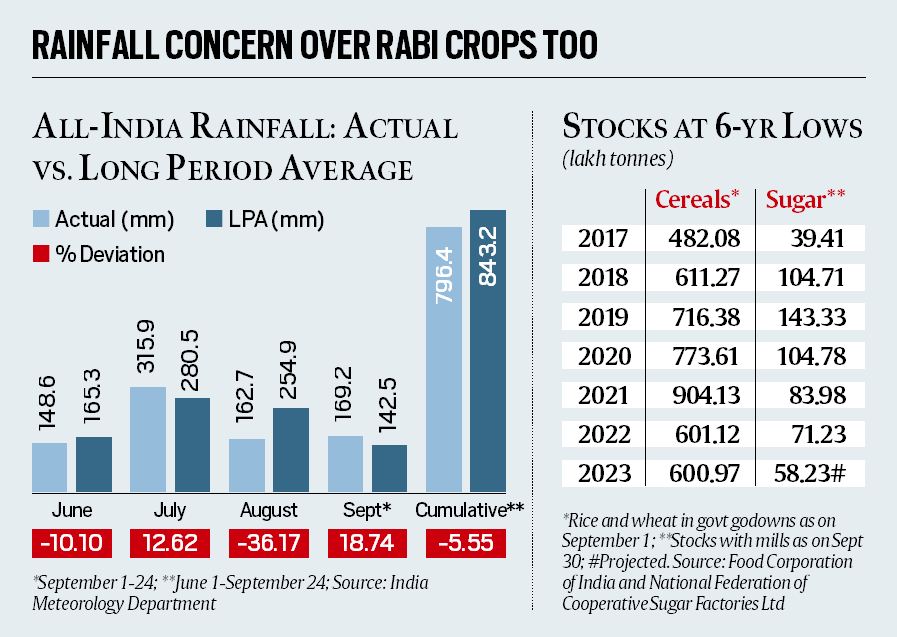

The monsoon has been erratic, arriving a week late in June that recorded overall 10.1% rainfall deficiency. But the 12.6% above-normal rain in July helped spur plantings of most kharif crops.

What followed, however, was the driest ever August since 1901. With an all-India 36.2% deficit, vis-à-vis the historical average precipitation for the month, the crops that were already sown experienced severe moisture stress.

July-August are usually the peak monsoon rainfall months, not only meeting the kharif crop’s requirements, but also filling up ponds and reservoirs and recharging groundwater tables. This time, it was the other way round: Farmers had to rely on releases from dams by irrigation departments and draw down underground water reserves to salvage their crops.

The Central Water Commission’s data shows water levels in 150 major reservoirs to have dipped to 111.737 billion cubic meters (BCM) as on September 6, 25.9% down from a year ago and 13.8% below the last 10 years’ average for this date.

Story continues below this ad

The 18.7% surplus rainfall in September so far (chart) has, apart from being a life-saver for the parched crops, raised the total reservoir water levels to 126.463 BCM. Although 19.5% below last year’s and 7.7% lower than the 10 years’ average for this time, it’s an improvement from the worst.

Benign effects

The September showers have been most beneficial for oilseeds, especially soyabean and groundnut, due for harvesting from this month-end.

The Indore-based Soyabean Processors Association of India had, on August 29, warned that the crop “will be adversely affected, causing lower yields” without “immediate rains”. The just-in-time monsoon turnaround has seemingly precluded that possibility.

A reasonably good kharif harvest, along with record imports, should allay any inflation fears in vegetable oils. India’s edible oil imports are set to top 16.5 million tonnes (mt) in the year ended October 2023, surpassing the previous all-time-high of 15.1 mt in 2016-17. Landed prices of imported crude palm oil have fallen to about $860 per tonne (from a July average of $945), and similarly to $990 (from $1,085) for soyabean and $885 ($1,000) for sunflower.

Story continues below this ad

Inflationary pressures have also eased in vegetables, whose consumer price index had jumped 37.4% year-on-year in July and 26.1% in August. That should come down sharply this month.

The all-India modal (most-quoted) retail price of tomato, as per the department of consumer affairs, is currently at Rs 20/kg, as against Rs 120 two months ago, and flat at Rs 20 for potato. Only onion has shown increase, from Rs 25 to Rs 30/kg. While there are concerns over the kharif onion crop – plantings have been lower and harvesting also likely to be delayed by a month from November – the Centre’s imposition of a 40% export duty has put a lid on prices for now.

Another commodity where the situation has turned comfortable is milk. In February-March, Maharashtra dairies were paying up to Rs 38 for a litre of cow milk with 3.5% fat and 8.5% solids-not-fat content, even as ex-factory prices of butter and skimmed milk powder hit Rs 430-435 and Rs 315-320 per kg respectively. Those prices have since crashed to Rs 34, Rs 350-360 and Rs 250-260 levels.

With the “flush” season for milk production starting from October, peaking through the winter and remaining high till next March-April, a further supply boost can be expected in the coming months. September rain has only helped, by augmenting the availability of fodder and also of feed ingredients from groundnut, soyabean and cottonseed oilcakes.

Supply worries

Story continues below this ad

These are mainly in three commodities: Cereals, sugar and pulses.

The accompanying table shows stocks of both cereals (rice and wheat in government godowns) and sugar (with mills) at six-year-lows.

Given that over a third of India’s paddy area is un-irrigated, and rainfall has been deficient in the whole of eastern UP, Bihar, Jharkhand and Gangetic West Bengal, a drop in kharif rice output cannot be ruled out this year. Moreover, the crop in large areas of Punjab and Haryana suffered inundation due to excess rain and water released from dams. Farmers there had to then re-transplant short-duration paddy varieties, including of basmati, yielding less than those planted earlier in June.

In sugar, the projected 5.8 mt stocks on September 30, ahead of the new crushing year from October, should suffice for 2.5 months of domestic consumption. That will cover the peak Dussehra-Diwali festival season, by which time mills would also start crushing. But it still makes for supply that is finely balanced – which explains why the Centre has banned export of sugar and much of rice.

Story continues below this ad

As regards pulses, there’s a clear shortfall – reflected in arhar (pigeon-pea), moong (green gram) and chana (chickpea) wholesaling at Rs 12,000, Rs 9,000 and Rs 6,000 per quintal respectively, above their corresponding minimum support prices of Rs 7,000, Rs 8,558 and Rs 5,335.

The rise in chana prices is significant, considering that government agencies held some 3.8 mt stocks at the end of its procurement season on June 30. It points to prices pressures on other pulses rubbing off on it as well. The situation isn’t helped by landed prices of masur (red lentil), the largest imported pulse, soaring more than $100 to $760-770 per tonne since late-July. Canada and Australia harvesting smaller crops – and the ongoing diplomatic tensions with the former – can potentially make matters worse.

Road ahead

The September amrit sanjeevani has provided some relief as far as the kharif crop goes.

The real challenge may be in the upcoming rabi (winter-spring) season, where the water for crops – from wheat, mustard and chana to potato, onion, garlic and jeera (cumin) – comes from underground aquifers and dams. The monsoon rain hasn’t been enough to fill up reservoirs or replenish groundwater tables.

Story continues below this ad

On top of that is El Niño. The US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration has predicted a 73% chance of average sea surface temperatures in the east-central equatorial Pacific Ocean ruling more than 1.5 degrees Celsius above normal during October-December and 78% probability of exceeding 1 degree in January-March 2024. That’s well above the 0.5 degrees El Niño threshold.

El Niño persisting through March 2024 could translate into subpar rain during the northeast monsoon (October-December) and winter (January-February) seasons. For farmers with already depleted ponds and groundwater reserves, it might make cultivation of rabi crops that much more difficult. That can also keep food inflation elevated till the national elections.