Wheat, in recent times, has been a victim of terminal heat stress – the tendency for mercury spikes in March, just when the crop is in the final grain formation and filling stage.

The current crop season has seen little of that: Maximum temperatures are near normal now in much of northwest and eastern India, while expected to gradually rise over the next 4-5 days.

With more than half of the grain-filling period – the 30-40 days of the kernels accumulating starch, proteins and other nutrient matter – completed in these major wheat-growing regions, and the crop already or near-harvested in central India, the chances of yield loss from an “Ides of March” heatwave strike seems low this time.

“The crop expression has been overall excellent in Punjab, Haryana, Uttar Pradesh (UP) and Bihar. We can expect high yields and quite good production in these states,” said Rajbir Yadav, principal scientist at the New Delhi-based Indian Agricultural Research Institute’s Division of Genetics.

A less-than-cold start

Yadav was, however, less sanguine about wheat production in central India – Madhya Pradesh (MP), Maharashtra, Gujarat and parts of Rajasthan – the reason being the late onset of winter.

The monthly average minimum temperature over central India was 1.67 degrees Celsius above normal in November, while 2.12 degrees higher in December 2023. The relatively warmer temperatures during these two months resulted in the premature initiation of flowering. The crop, whose earheads bearing the flowers (and eventually grain) should have taken 75-80 days to fully emerge from the wheat tillers, came to heading in 60-70 days.

While northwest and eastern India also registered above-normal temperatures in November-December, the deviations weren’t as high. Moreover, wheat sowing happens earlier in central India – from the last week of October to mid-November, as against the first half of November in northwest India and mid-November to mid-December in eastern UP and Bihar.

Story continues below this ad

The winter’s delayed arrival would have affected the crop sown earlier, cutting short its vegetative growth (of roots, stems and leaves) phase. The impact of it would have been more in central India, where the crop’s total growth duration is also only 125-130 days, as compared to 140-145 days in Punjab and Haryana.

While the winter did set in fully by late-December, the crop in central India suffered a further setback from foggy conditions and the lack of sunlight in January. The same wheat that flowered early, now also recorded poor pollination and seed setting. Thus, if early heading (induced by above-normal November-December temperatures) compromised the crop’s tillering and vegetative growth, seed formation (through pollen transfer from the male anther to the female stigma of the flower) was compromised by foggy weather in January.

“There has been a reduction in the number of tillers (shoots) per plant as well as seeds formed per spike (ear-head), which may both translate into lower grain yields in central India,” noted Yadav.

Production effect

Yadav’s analysis was seconded by Laxmi Narayan Dubliya, a wheat seed grower from Polayjagir village in Sonkatch tehsil of MP’s Dewas district: “Pehle do mahinon mein vipreet mausam raha. Fasal ko thand nahi mil payi (The weather was adverse in the first two months and not cold enough for the crop)”.

Story continues below this ad

Dubliya, also a director of the Dewas Kisan Producer Company Ltd, estimated the average yield in his area for the wheat sown during November-15 this time at 20 quintals per acre, down from last year’s 25 quintals. “Those who sowed earlier, during October 20-31, harvested hardly 14 quintals. Unke aur kam shakhayen bane (their crop developed fewer tillers),” he summed up.

Out of the total 34.2 million hectares (mh) area planted under wheat in the 2023-24 rabi season, MP alone accounted for 8.7 mh, with Gujarat and Maharashtra together adding another 2.3 mh. If the lower yields from central India are offset by bumper harvests in the northwest and east, the country can still end up producing more wheat than in 2022-23 and 2021-22.

The need for a better-than-average crop is all the more this year, given that wheat stocks in government godowns are at a seven-year-low (chart 1).

Wheat Stocks in Central Pool on March 1 (in lakh tonnes).

Wheat Stocks in Central Pool on March 1 (in lakh tonnes).

Tuber trouble

Wheat isn’t the only crop to be hit by an unusually warm November-December, followed by a cold but sunless January. Potato, too, has met a similar, if not worse, fate.

Story continues below this ad

According to Doongar Singh, a farmer-cum-cold store owner from Khandauli in Etmadpur tehsil of UP’s Agra district, potato requires sufficiently low temperatures during its planting time from mid-October to mid-November to enable vegetative growth.

“Is baar jab thand hui toh sooraj ka darshan nahi hua (even when temperatures fell in January, there was no sunlight)”, he pointed out. Thus, not only did fewer underground tubers get formed, their further development through photosynthesis was impeded due to inadequate sunlight. “Last year, yields were 250-300 packets (each of 50 kg) per acre. This year, we got 25-35 packets less,” he added.

Not surprising, then, that the Department of Consumer Affairs’ data shows potato retailing at Rs 20 per kg, compared to its year-ago all-India average modal (most-quoted) price of Rs 10. Retail prices of onion and tomato have posted similar increases – from Rs 20 to Rs 30 per kg each. In their case, dry weather and depleted water levels in reservoirs and aquifers – especially in Maharashtra and Karnataka – have led to a reduction in rabi-planted acreages as well.

Simply put, El Niño’s impact has extended beyond suppression of rainfall to also causing a warmer than usual winter.

Sweet story

Story continues below this ad

Amid this uncertainty over rabi crop prospects, there’s good news on one front: Sugar.

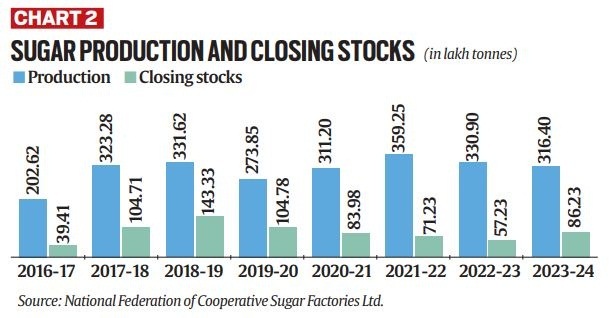

The last 2022-23 sugar year (October-September) had ended with stocks of 5.7 million tonnes (mt), the lowest since 2016-17. The current year is likely to see a production decline and yet closing stocks recovering to a four-year high of 8.6 mt (chart 2).

Sugar Production and Closing Stocks (in lakh tonnes).

Sugar Production and Closing Stocks (in lakh tonnes).

Prakash Naiknavare, managing director of the National Federation of Cooperative Sugar Factories, attributed the turnaround to two factors. The first was Maharashtra receiving good rain in November and December, ending a prolonged dry spell and providing a lifeline to the standing cane.

The second was the Centre’s decision in December 2023 to restrict the usage of sugarcane juice/syrup and intermediate-stage ‘B-heavy’ molasses for the production of ethanol.

Story continues below this ad

“We originally projected Maharashtra’s production at 9 mt, which have since been revised upwards to 10.4 mt. We are also estimating only 1.7 mt of sugar at all-India level to be diverted for ethanol in 2023-24, compared to 4.5 mt, 3.4 mt and 2.2 mt in the preceding years. Both factors will contribute to higher than expected output and a comfortable stocks position,” Naiknavare told The Indian Express.

Wheat Stocks in Central Pool on March 1 (in lakh tonnes).

Wheat Stocks in Central Pool on March 1 (in lakh tonnes). Sugar Production and Closing Stocks (in lakh tonnes).

Sugar Production and Closing Stocks (in lakh tonnes).