Why should the bankruptcy of a Cleveland-based auto parts company, manufacturing spark plugs and windscreen-wipers, and the collapse of a relatively small auto sector lender Tricolor, trigger turmoil on Wall Street?

As Jamie Dimon, the head of JPMorgan Chase, America’s biggest bank, said in a prophetic warning last week after both Tricolor and First Brands went belly up: “Probably shouldn’t say this, but when you see one cockroach, there are probably more”.

There are at least three ominous red flags that the two bankruptcies herald, which point to these not being the last of the headwinds faced by America’s credit market.

Multiple warnings

Story continues below this ad

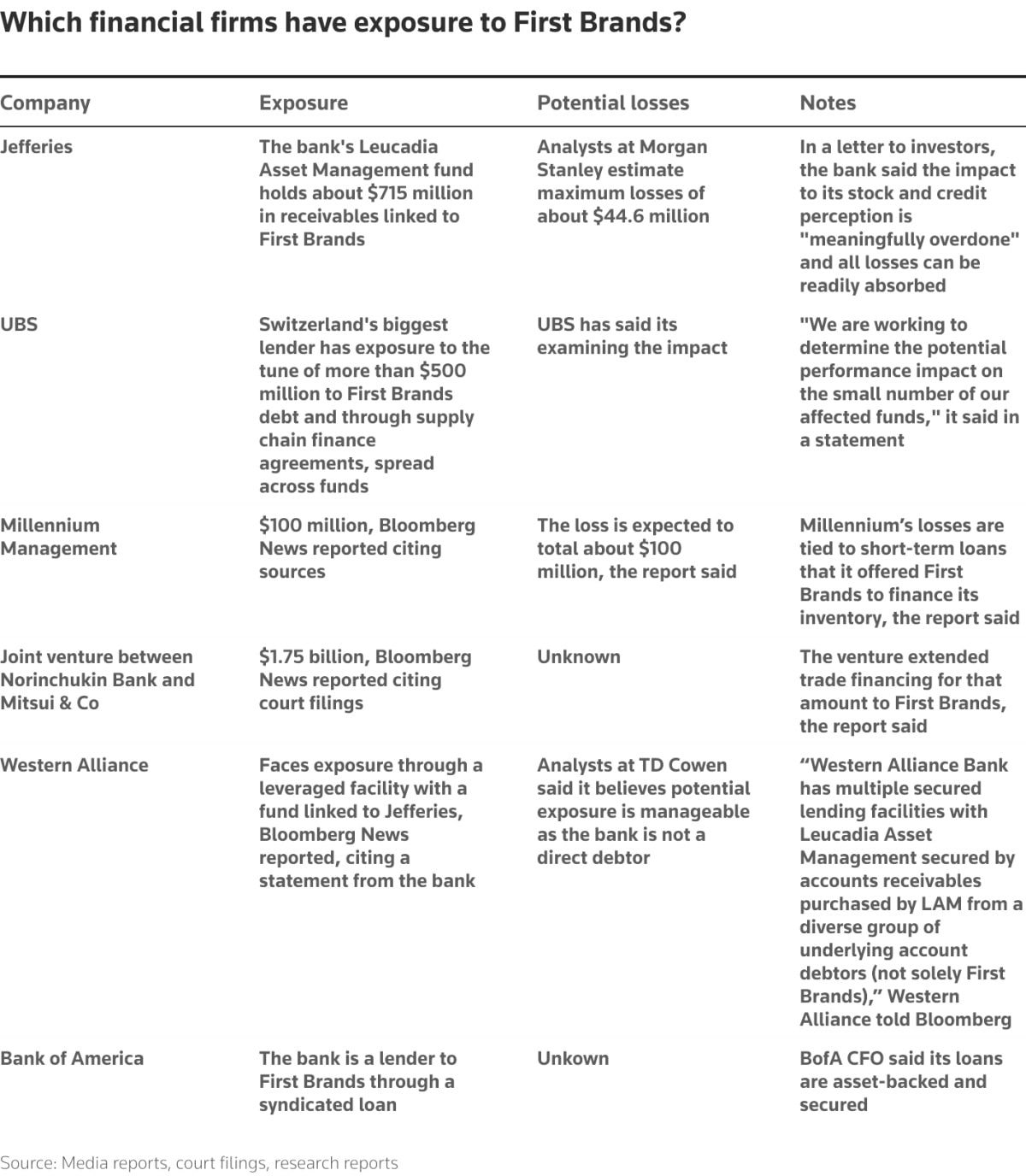

First, the scale of collateral impact. When First Brands filed for bankruptcy protection late last month, weeks after the Tricolor blow-up, it listed more than $10 billion in liabilities. American credit markets were rattled primarily because it laid bare the exposure of some of the world’s top financial institutions to the auto parts maker.

US investment bank Jefferies and Swiss lender UBS had exposure running into millions of dollars. Reuters reported that Morgan Stanley’s asset management unit had asked Jefferies to return some of its investment in a fund exposed to the bankrupt auto parts maker. A joint venture between Japan’s Norinchukin Bank and Mitsui & Co faced nearly $2 billion of exposure to the auto parts supplier, Bloomberg News reported, while Reuters reported Bank of America Chief Financial Officer Alastair Borthwick as saying that the lender’s syndicated loans to First Brands were relatively hedged — “asset-backed” and “secured by collateral”.

Exposure to First Brands. (Via Reuters)

Exposure to First Brands. (Via Reuters)

Millennium, a New York-based hedge fund, also had exposure, while short sellers such as Apollo Global Management and Diameter Capital Partners, too, were involved, even though both funds have subsequently said they have now closed their short positions. JPMorgan Chase said it “re-examined its controls” after finding itself exposed, although broadly banks insist that American borrowers’ credit quality is robust.

Second, First Brands’ creditors put in funding through complex financial structures such as collateralised-fund obligations and business-development companies. Not very dissimilar from the infamous collateralised-debt obligations — a complex financial product, which pooled together various debt instruments, such as mortgages, bonds, or loans, and repackaged them into discrete tranches with different risk profiles — that played a significant role in the 2008 financial crisis.

Story continues below this ad

Such instruments continue to be essential components of structured finance in the US. According to The Economist, sweeping changes to credit markets since the financial crisis of 2007-09 “have made diligence harder”. In the case of First Brands, the company’s borrowing against inventory and money owed to it by customers, prima facie, appeared to be “excessive”. Also, such receivables are difficult to monitor and there is apprehension that the company could have borrowed against the same assets more than once.

Third, the First Brands bankruptcy and worries over this sort of credit is nothing new. The collapse in 2021 of Greensill Capital, a UK-based financial-services company that made similar loans, ought to have put investors on alert. In March 2021, Greensill Capital collapsed into insolvency after much of its debt was found to be backed by projections of future sales rather than invoices. The same formula that First Brands was found to be using just years later. Incidentally, Greensill Capital’s riskier loans were funded, in part, by investors and even bank depositors seeking a safe place to invest their money.

The First Brands debacle is unlikely to be the only one in the market. Meanwhile, Tricolor was among the fastest-growing auto lenders in the United States over the last five years, till it declared bankruptcy.

Deep systemic rot

The problems at First Brands came to light when scrutiny of the auto parts maker intensified in August after it suddenly halted a proposed refinancing of its debt, forcing investors to call for a third-party review of the accounts. The bigger worry is that some of these loans were arranged by respectable banks. Had First Brands’ creditors been entirely banks, there could have been a run by depositors, setting off a far bigger crisis.

Story continues below this ad

Given that it is not the case, the immediate impact of the First Brands blow up would be on funds with exposure. But it is highly likely that the instruments being used by First Brands were also being used by others. The more-widespread macro impact is what is worrying the markets, and the skeletons are still only tumbling out. Moreover, these two bankruptcies come when the going is still good for the markets, helped by the artificial intelligence (AI) wave that continues to push up stock valuations in the US. Had this come during a downslide in market sentiments, both the bankruptcies could have played out differently.

Fuelled by enthusiasm for AI, American stock markets have continued to surge, with many on Wall Street now believing that the run could be about to come to an end. Concerns about the health of America’s borrowers could trigger stress in funding markets, with indicators such as the secured overnight financing rate, the interbank-lending benchmark, reported to have climbed to an over five-year high.

This potentially suggests rising demand for liquidity among banks, and a reluctance to lend among themselves cheaply. That could be a cause for concern, indicating that the market knows the extent of the systemic problem.

“Although the broader risk of contagion appears contained for now, a loss of confidence could still trigger significant stress,” Morningstar analyst Kenneth Lamont was quoted as saying in a Reuters report. “A broader sell-off in private credit and mass redemptions would expose these vehicles to their first real test, bringing liquidity mismatches to the surface and putting portfolio valuations under pressure.”

Story continues below this ad

Meanwhile, the US Department of Justice has launched an inquiry into the collapse of First Brands, Reuters reported earlier this week. A group of creditors are set to provide the company with $1.1 billion in debtor-in-possession financing to keep operations running, according to a statement last Monday. The scale of the blow-up is only going to come out in the coming weeks.

Exposure to First Brands. (Via Reuters)

Exposure to First Brands. (Via Reuters)