‘Grammar’s greatest puzzle’: What was the Sanskrit problem in Panini’s ‘Ashtadhyayi’, now solved by an Indian student?

At 27, Rishi Rajpopat may have decoded a puzzle that has confused scholars for centuries.

Rishi Rajpopat; and (right) a medieval textbook based on Panini's rules for Sanskrit. (Sources: Cambridge University, Wellcome Images)

Rishi Rajpopat; and (right) a medieval textbook based on Panini's rules for Sanskrit. (Sources: Cambridge University, Wellcome Images) In his PhD thesis published on December 15, Cambridge scholar Dr Rishi Rajpopat claims to have solved Sanskrit’s biggest puzzle—a grammar problem found in the ‘Ashtadhyayi’, an ancient text written by the scholar Panini towards the end of the 4th century BC. Experts are calling the discovery revolutionary, as it may allow Panini’s grammar to be taught to computers for the first time.

What exactly was the problem?

Written more than 2,000 years ago, the ‘Ashtadhyayi’ is a linguistics text that set the standard for how Sanskrit was meant to be written and spoken. It delves deep into the language’s phonetics, syntax and grammar, and also offers a ‘language machine’, where you can feed in the root and suffix of any Sanskrit word, and get grammatically correct words and sentences in return.

To ensure this ‘machine’ was accurate, Panini wrote a set of 4,000 rules dictating its logic. But as scholars studied it, they found that two or more of the rules could apply at the same time, causing confusion. To resolve this, Panini had provided a ‘meta-rule’ (a rule governing rules), which had historically been interpreted as:

‘In the event of a conflict between two rules of equal strength, the rule that comes later in the serial order of the ‘Ashtadhyayi’ wins’.

However, following this interpretation did not solve the machine’s problem. It kept producing exceptions, for which scholars had to keep writing additional rules. This is where Dr Rishi Rajpopat’s discovery came through.

An answer ‘lost in translation’

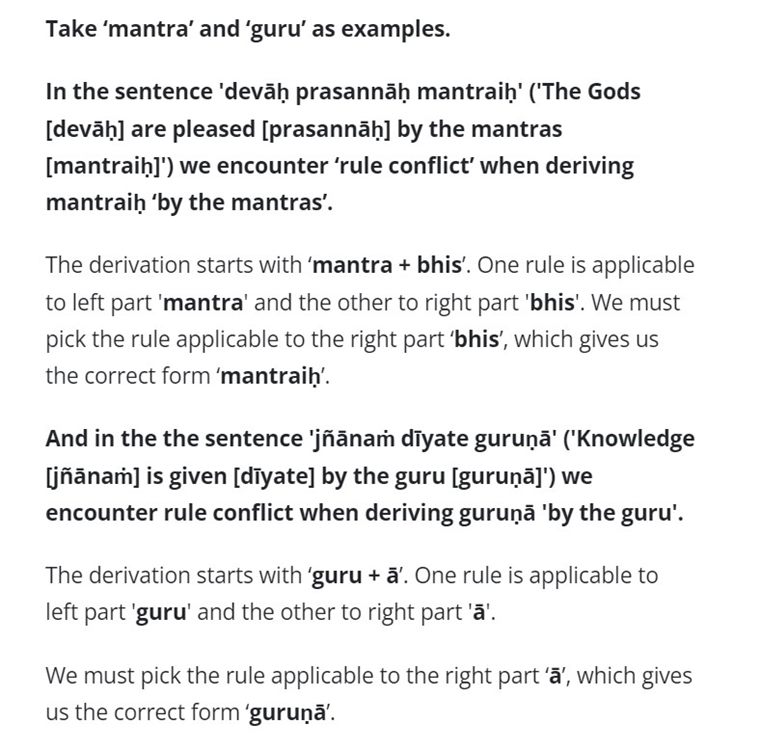

In his thesis titled ‘In Panini We Trust’, Dr Rajpopat took a simpler approach, arguing that the meta-rule has been wrongly interpreted throughout history; what Panini actually meant, was that for rules applying to the left and right sides of a word, readers should use the right-hand side rule.

Using this logic, Dr Rajpopat found that the ‘Ashtadhyayi’ could finally become an accurate ‘language machine’, producing grammatically sound words and sentences almost every time.

The discovery now makes it possible to construct millions of Sanskrit words using Panini’s system—and since his grammar rules were exact and formulaic, they can act as a Sanskrit language algorithm that can be taught to computers.

Example of how to interpret Panini’s meta-rule, as explained by Dr Rajpopat, to get the correct form of words. (Source: Cambridge University)

Example of how to interpret Panini’s meta-rule, as explained by Dr Rajpopat, to get the correct form of words. (Source: Cambridge University)

Why did it take so long to crack the ‘puzzle’?

According to Dr Rajpopat, it’s because of how Sanskrit academia has operated so far, where scholarship is built upon the writings of other scholars, and not necessarily the original text.

Katyayayana, another ancient scholar, was also familiar with two interpretations of Panini’s work. But according to Dr Rajpopat, Katyayana misunderstood the meta-rule, and his wrong interpretation got compounded over centuries.

Panini, the ‘father of linguistics’

Panini probably lived in the 4th century BC, the age of the conquests of Alexander and the founding of the Mauryan Empire, even though he has also been dated to the 6th century BC, the age of The Buddha and Mahavira.

He likely lived in Salatura (Gandhara), which today would lie in north-west Pakistan, and was probably associated with the great university at Taksasila, which also produced Kautilya and Charaka, the ancient Indian masters of statecraft and medicine respectively.

By the time Panini’s great grammar, the ‘Ashtadhyayi’, or ‘Eight Chapters’, was composed, Sanskrit had virtually reached its classical form — and developed little thereafter, except in its vocabulary — the Indologist A L Basham wrote in his 1954 textbook, ‘The Wonder That Was India’.

Panini’s grammar, which built on the work of many earlier grammarians, effectively stabilised the Sanskrit language, Basham wrote. The earlier works had recognised the root as the basic element of a word, and had classified some 2,000 monosyllabic roots which, with the addition of prefixes, suffixes and inflexions, were thought to provide all the words of the language.

Panini, the ‘father of linguistics’, in a 2004 stamp issued by the Govt of India.

Panini, the ‘father of linguistics’, in a 2004 stamp issued by the Govt of India.

The Ashtadhyayi laid down more than 4,000 grammatical rules, couched in a sort of shorthand, which employs single letters or syllables for the names of the cases, moods, persons, tenses, etc. in which linguistic phenomena are classified, Basham wrote. Later Indian grammars such as the Mahabhasya of Patanjali (2nd century BC) and the Kasika Vritti of Jayaditya and Vamana (7th century AD), were mostly commentaries on Panini.

“Though its fame is much restricted by its specialized nature, there is no doubt that Panini’s grammar is one of the greatest intellectual achievements of any ancient civilization, and the most detailed and scientific grammar composed before the 19th century in any part of the world,” Basham wrote.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05