Warming up to climate change: What is carbon capture and can it help save the planet?

In this series of explainers, we answer some of the most fundamental questions about climate change, the science behind it, and its impact. In the ninth instalment, we answer the question: 'What is carbon capture and can it help save the planet? '

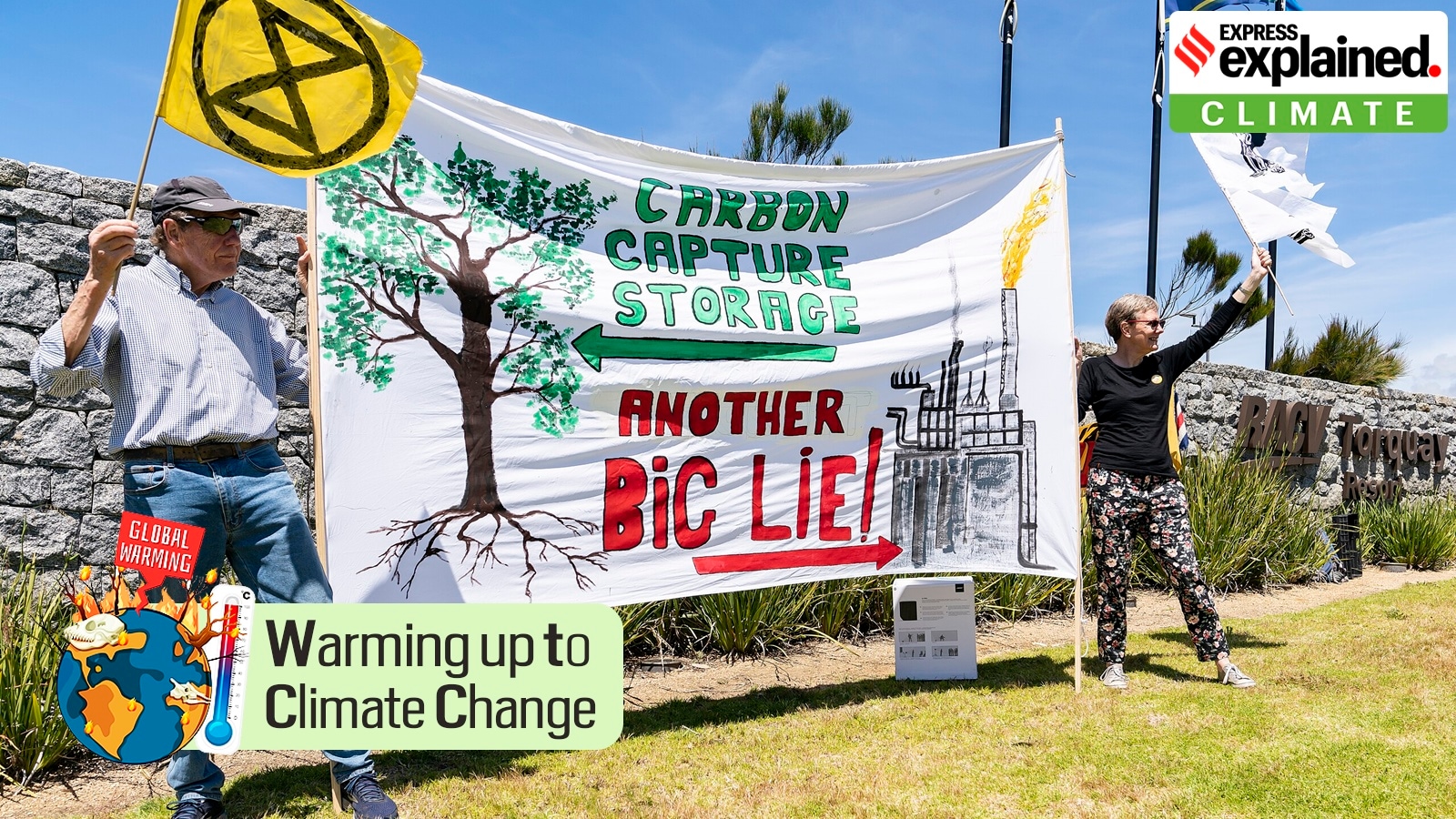

A protest aganst carbon capture and storage in Torquay, England. (Wikimedia Commons)

A protest aganst carbon capture and storage in Torquay, England. (Wikimedia Commons)Last week, Germany announced that it would allow carbon capture and off-shore storage for certain industrial sectors, such as cement production, to help meet its target of becoming carbon neutral by 2045. The country is currently the biggest carbon dioxide (CO2) emitter in Europe.

Several other countries have also either implemented carbon capture and storage (CCS) technologies or plan to do so. For instance, in November 2023, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) launched a project to suck carbon directly from the air and convert it into rock.

With the planet getting warmer due to unprecedented greenhouse gas (GHG) levels, some see carbon capture as a silver bullet that could tackle climate change.

But can carbon capture actually help save the planet? We take a look at the question in this week’s edition of Warming up to Climate Change — a series of explainers, in which we answer some of the most fundamental questions about climate change, the science behind it, and its impact. You can scroll down to the end of this article for the first eight parts of the series.

First, what is carbon capture and storage?

Simply put, CCS refers to a host of different technologies that capture CO2 emissions from large point sources like refineries or power plants and trap them beneath the Earth. Notably, CCS is different from carbon dioxide removal (CDR), where CO2 is removed from the atmosphere.

CCS involves three different techniques of capturing carbon, including post-combustion, pre-combustion, and oxyfuel combustion.

In post-combustion, CO2 is removed after the fossil fuel has been burnt. By using a chemical solvent, CO2 is separated from the exhaust or ‘flue’ gases and then captured.

Pre-combustion involves removing CO2 before burning the fossil fuel. “First, the fossil fuel is partially burned in a ‘gasifier’ to form synthetic gas. CO2 can be captured from this relatively pure exhaust stream,” according to a report by the British Geological Survey. The method also generates hydrogen, which is separated and can be used as fuel.

In oxyfuel combustion, the fossil fuel is burnt with almost pure oxygen, which produces CO2 and water vapour. The water is condensed through cooling and CO2 is separated and captured. Out of the three methods, oxyfuel combustion is the most efficient but the oxygen burning process needs a lot of energy.

Post-combustion and oxyfuel combustion equipment can be retro-fitted in existing plants that were originally built without them. Pre-combustion equipment, however, needs “larger modifications to the operation of the facility and are therefore more suitable to new plants,” according to a report by the London School of Economics (LSE).

After capture, CO2 is compressed into a liquid state and transported to suitable storage sites. Although CO2 can be transported through ship, rail, or road tanker, pipeline is the cheapest and most reliable method.

Can carbon capture help save the world?

Operational CCS projects generally claim to be 90 per cent efficient, meaning they can capture 90 per cent of carbon and store it. Studies, however, have shown that a number of these projects are not as efficient as they claim to be. For example, a 2022 study by the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA) — a global think tank that examines issues related to energy markets, trends, and policies — found most of the 13 flagship CCS projects worldwide that it analysed have either underperformed or failed entirely.

Moreover, CCS technologies are quite expensive. “When CCS is attached to coal and gas power stations it is likely to be at least six times more expensive than electricity generated from wind power backed by battery storage,” a report by Climate Council, Australia’s leading climate change communications non-profit organisation, said. It is far cheaper and more efficient to avoid CO2 emissions in the first place, the report added.

There are also only a few operational CCS projects across the world even though the technology has been pushed for decades. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), there were 40 operational CCS projects in 2023, which captured more than 45 metric tonnes (Mt) of CO2 annually — China’s annual emissions in 2021 alone stood at 12,466.32 Mt.

Rise in carbon dioxide levels. Credit: NASA

Rise in carbon dioxide levels. Credit: NASA

To ensure the planet doesn’t breach the 1.5 degree Celsius temperature increase limit, it would take an “inconceivable” amount of carbon capture “if oil and natural gas consumption were to evolve as projected under today’s policy settings,” the IEA said in a report. It added that the electricity required to capture that level of carbon as of 2050 would be more than the entire planet’s use of electricity in 2022. Therefore, the IEA report said there couldn’t be an overreliance on carbon capture as a solution to tackle climate change.

Speaking to the Deutsche Welle (DW) news agency, Genevieve Gunther, founder of End Climate Silence, a volunteer organisation dedicated to help the news media cover the climate crisis, said the issue is not that CCS projects don’t work as effectively as they advertise. CCS rather gives fossil fuel companies a “social licence to operate”.

“They’re not using carbon capture as a climate solution. They’re using it to actually enhance extraction,” she added.

Here are the previous instalments of the series: part 1, part 2, part 3, part 4, part 5, part 6, part 7, and part 8.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05