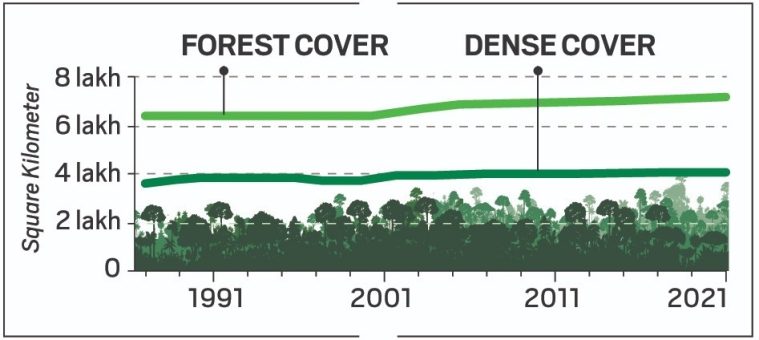

India is one of the few countries to have a scientific system of periodic forest cover assessment that provides “valuable inputs for planning, policy formulation and evidence-based decision-making”. Since 19.53% in the early 1980s, India’s forest cover has increased to 21.71% in 2021. Adding to this a notional 2.91% tree cover estimated in 2021, the country’s total green cover now stands at 24.62%, on paper.

While the Forest Survey of India (FSI) started publishing its biennial State of Forest reports in 1987, it has been mapping India’s forest cover since the early 1980s.

India counts all plots of 1 hectare or above, with at least 10% tree canopy density , irrespective of land use or ownership, within forest cover. This disregards the United Nation’s benchmark that does not include areas predominantly under agricultural and urban land use in forests.

All land areas with tree canopy density of 40% and above are considered dense forests and those between 10-40% are open forests. Since 2003, a new category — very dense forest — was assigned to land with 70% or more canopy density.

All land areas with tree canopy density of 40% and above are considered dense forests and those between 10-40% are open forests. Since 2003, a new category — very dense forest — was assigned to land with 70% or more canopy density.

All land areas with tree canopy density of 40% and above are considered dense forests and those between 10-40% are open forests. Since 2003, a new category — very dense forest — was assigned to land with 70% or more canopy density.

Since 2001, isolated or small patches of trees — less than 1 hectare and not counted as forest — are assessed for determining a notional area under tree cover by putting together the crowns of individual patches and trees.

NRSA versus FSI

The National Remote Sensing Agency (NRSA) under the Department of Space estimated India’s forest cover using satellite imagery for periods 1971-1975 and 1980-1982 to report a loss of 2.79% — from 16.89% to 14.10% — in just seven years.

While reliable data on encroachment is unavailable, government records show that 42,380 sq km — nearly the size of Haryana— of forest land was diverted for non-forest use between 1951 and 1980.

Story continues below this ad

However, the government was reluctant to accept such a massive loss and, after much negotiations, the NRSA and the newly established FSI “reconciled” India’s forest cover at 19.53% in 1987.

Significantly, the FSI did not contest the NRSA finding that the dense forest cover had fallen from 14.12% in the mid-1970s to 10.96% in 1981, and reconciled it to 10.88% in 1987.

Old forests lost

In India, land recorded as forest in revenue records or proclaimed as forest under a forest law is described as Recorded Forest Area. These areas were recorded as forests at some point due to the presence of forests on the land. Divided into Reserved, Protected and Unclassed forests, Recorded Forest Areas account for 23.58% of India.

A residential area in Delhi’s Dhaula Kuan shows up as dense forest on India’s forest map

A residential area in Delhi’s Dhaula Kuan shows up as dense forest on India’s forest map

Over time, some of these Recorded Forest Areas lost forest cover due to encroachment, diversion, forest fire etc. And tree cover improved in many places outside the Recorded Forest Areas due to agro-forestry, orchards etc.

Story continues below this ad

In 2011, when the FSI furnished data on India’s forest cover inside and outside Recorded Forest Areas, it came to light that nearly one-third of Recorded Forest Areas had no forest at all. In other words, almost one-third of India’s old natural forests — over 2.44 lakh sq km (larger than Uttar Pradesh) or 7.43% of India — were already gone.

Of what remains of forests in Recorded Forest Areas, only a fraction is dense forests.

Natural forests shrink

Even after extensive plantation by the forest department since the 1990s, dense forests within Recorded Forest Areas added up to cover only 9.96% of India in 2021. That is a one-tenth slide since the FSI recorded 10.88% dense forest in 1987.

This loss remains invisible due to the inclusion of commercial plantations, orchards, village homesteads, urban housings etc as dense forests outside Recorded Forest Areas. The SFR 2021, for example, reports 12.37% dense forest by including random green patches like the ones The Indian Express sampled.

Story continues below this ad

The FSI provides no specific information on the share of plantations in the remaining dense forests inside Recorded Forest Areas. But its data offers some hints. Since 2003, nearly 20,000 sq km of dense forests have become non-forests. Much of that loss is compensated by nearly 11,000 sq km of non-forest areas that became dense forests in successive two-year windows since 2003.

These are plantations, say experts, since natural forests do not grow so fast.

Natural vs manmade

The steady replacement of natural forests with plantations are worrisome. First, natural forests have evolved naturally to be diverse and, therefore, support a lot more biodiversity. Simply put, it has many different plants to sustain numerous species.

Secondly, plantation forests have trees of the same age, are more susceptible to fire, pests and epidemics, and often act as a barrier to natural forest regeneration.

Story continues below this ad

Thirdly, natural forests are old and therefore stock a lot more carbon in their body and in the soil. In 2018, the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) flagged India’s assumption that new forests (plantations) reach the carbon stock level of existing forests in just eight years.

On the other hand, plantations can grow a lot more and faster than old natural forests. This also means that plantations can achieve additional carbon targets faster. But compared to natural forests, plantations are often harvested more readily, defeating carbon goals in the long term.

Sharp images, soft data

Until the mid-1980s (SFR 1987), the forest cover was estimated through satellite images at a 1:1 million scale. The resolution then improved to 1:250,000, reducing the minimum mappable unit size from 400 to 25 hectares.

Since 19.53% in the early 1980s, India’s forest cover has increased to 21.71% in 2021.

Since 19.53% in the early 1980s, India’s forest cover has increased to 21.71% in 2021.

By 2001, the scale improved to 1:50,000, bringing down the unit size to 1 hectare, and interpretation went fully digital.

Story continues below this ad

One outcome of this refinement of the scale was that the forest cover fell within the forest area while it increased outside. That is because “many small blank, non-forested and/or degraded forest patches” became discernible within the forest land that earlier appeared as a larger green chunk. Similarly, several small woodlots or plantations outside forest areas became visible.

The forest cover fluctuated with every change in technology and the radical refinement in 2001 made the data incomparable with the previous assessments. But the FSI also got into a habit of revising its data in every successive report ever since.

Between 1997 and 2005, our forest cover jumped by 9%, gaining 56,774 sq km, and dense forest cover increased by 10% or 36,160 sq km. Since 2015, the total gain is 12,294 sq km, including 5,297 sq km of dense forests.

Open, participatory

The FSI compares some interpreted data with the corresponding reference data collected from the ground under the National Forest Inventory (NFI) programme. In 2021, it claimed to have established an overall accuracy of 95.79% in identifying forests from non-forests. However, given the limited resources, the exercise was limited to less than 6,000 sample points.

Story continues below this ad

Yet, the FSI never made its data freely available for public scrutiny. Inexplicably, It also bars the media from accessing its geo-referenced maps.

“In 1995, we shifted to our own satellite. The forest maps are based on the images purchased from NRSA, another arm of the government. Look at Brazil. They are losing forests at an alarming rate. But whatever be the quality, their forest data is open and free,” a former Environment ministry official said.

Brazil’s National Institute for Space Research (INPE) maintains an open web platform, TerraBrasilis, for queries, analysis and dissemination of data on deforestation, forest cover change and forest fire.

Since lack of manpower limits the FSI’s scope for verifying the quality of remotely sensed data in the field, making the field data freely available to the public may also ease its burden.

Story continues below this ad

With environmental awareness on the rise, say experts, thousands of researchers and enthusiasts can volunteer to verify the country’s forest data on the ground and be proud custodians of this vital national asset.

All land areas with tree canopy density of 40% and above are considered dense forests and those between 10-40% are open forests. Since 2003, a new category — very dense forest — was assigned to land with 70% or more canopy density.

All land areas with tree canopy density of 40% and above are considered dense forests and those between 10-40% are open forests. Since 2003, a new category — very dense forest — was assigned to land with 70% or more canopy density. A residential area in

A residential area in

Since 19.53% in the early 1980s, India’s forest cover has increased to 21.71% in 2021.

Since 19.53% in the early 1980s, India’s forest cover has increased to 21.71% in 2021.