Why Israel has imprisoned an 18-year-old ‘conscientious objector’, what the term means

Tal Mitnik will spend 30 days in prison for refusing to join the Israeli military. We take a look at the concept of a conscientious objector, laws and debates surrounding it, and some famous examples from the past, notably, boxing legend Muhammad Ali.

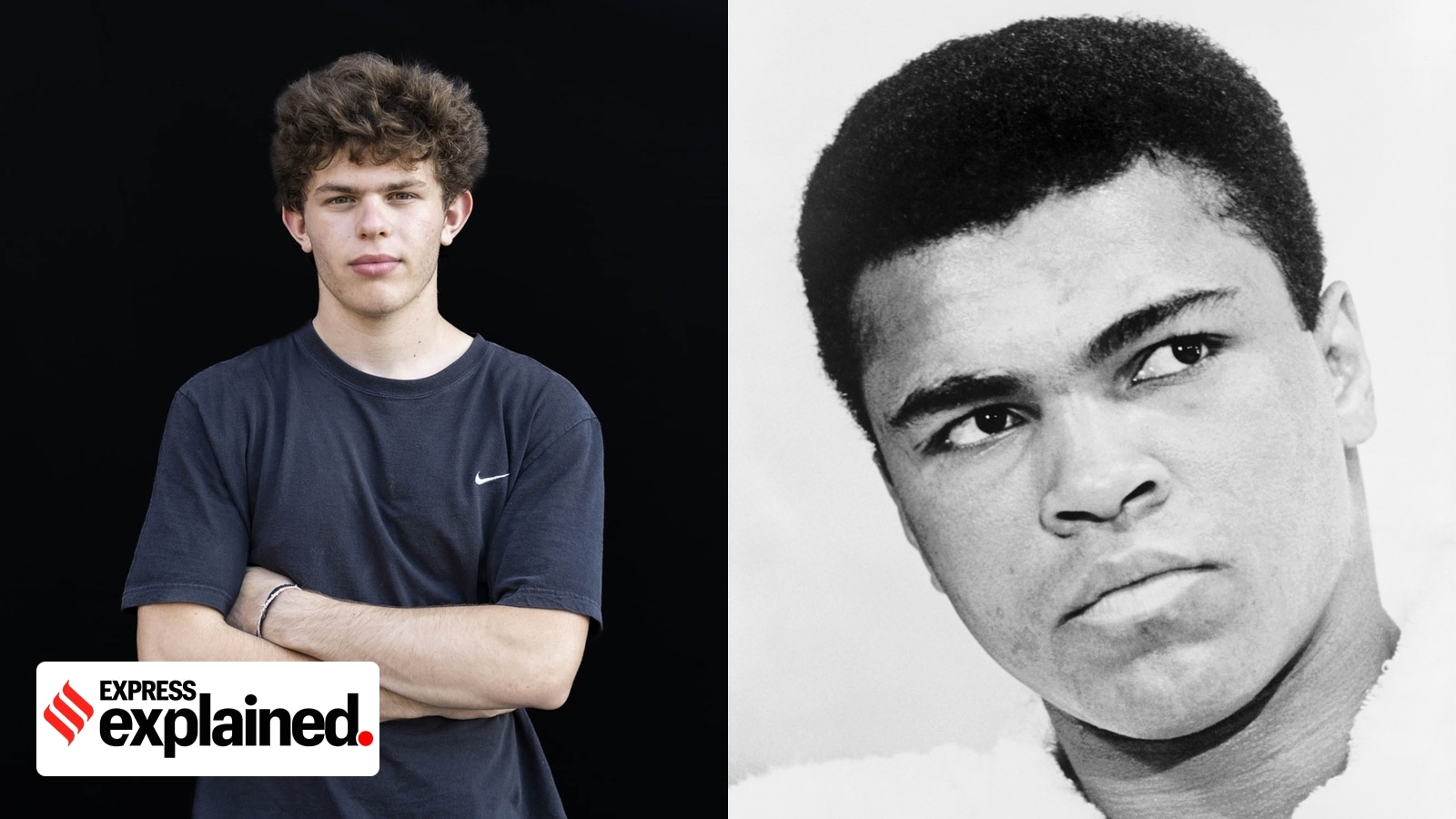

Just like Muhammad Ali (right) during the Vietnam War in the US, Tal Mitnick has been slapped with a prison sentence for being a conscientious objector. (Twitter/@TalMitnick, Wikimedia Commons)

Just like Muhammad Ali (right) during the Vietnam War in the US, Tal Mitnick has been slapped with a prison sentence for being a conscientious objector. (Twitter/@TalMitnick, Wikimedia Commons)Tal Mitnik, 18, will spend 30 days in prison for refusing to serve in the Israeli military and take part in its assault on Gaza.

“I do not want to take part in the continuation of the oppression and the continuation of the cycle of bloodshed, but to work directly for a solution, and therefore I refuse,” he wrote in a public statement.

Israeli law mandates that all citizens serve in the military for a certain duration. Those who refuse are socially ostracised and persecuted by the state. We take a look at the concept of a conscientious objector, laws and debates surrounding it, and some famous examples from the past.

Laws are made by people

And people can be wrong

Once unions were against the law

But slavery was fine

Women were denied the vote

While children worked the mine

The more you study history

The less you can deny it

Say a rotten law stays on the books

‘Til folks with guts defy it— tal🫒 (@TalMitnick) December 25, 2023

Who is a conscientious objector?

A conscientious objector is an individual who refuses to perform military service on the grounds of their conscience, often for ideological and religious reasons.

Throughout history, armies across the world have been supplied manpower using conscription, or mandatory military service. Naturally, there have always been those who have refused this call to serve, citing their personal beliefs.

The earliest documented conscientious objector was Maximilianus, a 21-year-old who refused to serve as a soldier in the Roman army in 295 CE. He would be executed for his refusal and later canonised as Saint Maximilian.

The first self-identified conscientious objectors appeared during World War I, when basically all belligerents resorted to conscription to meet the needs of war. It is estimated that more than 16,000 conscientious objectors refused military service in the UK, and about 4,000 in the US during the war.

How are conscientious objectors dealt with?

Explicit conscientious objection legislation emerged in Western countries during and after World War I. At the time, countries struggling to meet the War’s manpower requirements either completely forbade conscientious objection, or allowed it in very limited circumstances.

For instance, of the 16,000 British conscientious objectors, most of whom were pacifist Quakers, 6,000 were refused any exemption, court-martialed, and sent to prison in case they continued to resist military service.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, adopted by the UN General Assembly in 1948, for the very first time enshrined the right to “conscience” in international law. “Everyone has the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion,” Article 18 of the declaration states. This was further emphasised upon in the 1976 International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.

In 1995, the United Nations Commission on Human Rights became even more explicit in its advocacy of conscientious objection as a right. Resolution 1995/83 states that “persons performing military service should not be excluded from the right to have conscientious objections to military service.”

However, despite what the UN and other human right organisations say, conscientious objection still does not have legal basis in most countries with conscripted militaries. Even in countries where it does, it is highly restricted.

For instance, in Israel the right to conscientious objection is legally extended only to Haredi Jews studying religious scriptures in traditional yeshiva schools.

Who are some of the most famous conscientious objectors in modern history?

During World War II, conscientious objector Desmond Doss was awarded the Medal of Honour, the United States’ highest military honour. While Doss had voluntarily joined the army, he refused to touch a weapon citing his religious beliefs. After some tensions with the hierarchy, he was assigned the role of a medic, which he performed admirably and at great risk to his own life. The film Hacksaw Ridge (2016) is based on his life and his exploits during the Battle of Okinawa (1945).

The most famous conscientious objector of all time is none other than the great Muhammad Ali (1942-2016). In 1967, as the reigning world heavyweight champion, Ali refused induction into the military, saying the war in Vietnam was against the teachings of the Quran.

“Man, I ain’t got no quarrel with Viet Cong,” Ali would later elaborate. “Why should they ask me to put on a uniform and go ten thousand miles from home and drop bombs and bullets on brown people in Vietnam while so-called Negro people in Louisville are treated like dogs and denied simple human rights?” he said.

He was convicted of draft evasion, and given the maximum penalty: a $10,000 fine and five years in prison. Although he would stay out of prison, while his appeal against the conviction made its way to the US Supreme Court, he was stripped of his title and not allowed to box until 1971, when the apex court unanimously overturned Ali’s conviction.

His principled resistance made him an icon of the Civil Rights and Anti-War movement in the United States.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05