Click here to follow Screen Digital on YouTube and stay updated with the latest from the world of cinema.

‘What’s the point in making a film only for your followers?’

Filmmaker Sanal Kumar Sasidharan on his award-winning film S Durga, fighting censorship and why he never wants to direct a commercial film.

Sanal Sasidharan

Sanal Sasidharan

In S Durga, a couple looking to get a ride late at night are forced to negotiate whether it is safer to be out on the streets or to accept a stranger’s offer. It’s been described as an off-beat road movie. Did you set out to make one?

I had no idea about the genre of the film — I wanted to make a film through which I could say something. So, I’m not bothered if it’s going to be considered a road movie, or a thriller, or any other genre.

Your battle with the censors began in February this year. Twenty-one audio mutes later, and the blurring/changing of the title, what have you learned about being a filmmaker in India today?

You have to be very clever and tactical. These days, making a film is easy. If you have an idea and people like it, they will donate money. Your struggle starts once you’ve made the film — you want to save it from those who want to butcher it, whether it is institutions or fringe groups. This sena, that sena (laughs) will pop up right before the release of your film and say that they don’t like the name. But we can’t treat these people as outsiders or as our permanent enemies. We’re not just making films for those who understand cinema, but for everybody, especially those who don’t agree with us. If they watch it, they might rethink their position. What’s the point in making a film only for your followers?

Do you plan to take it beyond festivals?

I want to release it as a regular film. I want to invite everybody, even those who have threatened me, to come and see the film. These people have got a certain power and vindication now, thanks to the political situation (in India). Look, the Censor Board has seen my film and they said there’s nothing against goddess Durga, but they still want to alter the title so as not to offend anybody’s religious sentiments. They said there were 1,000 complaints. In a country of 1.3 billion people, you want me to chop my film’s name for 1,000 people? That means that this institution is speaking the same language as those 1,000 people. We can’t escape this process — either we say that democracy is lost and we need to start a revolution, or we need to have a discussion and debate.

If you could be in the same room with them, what would you say?

What I want to tell those who oppose my film on religious grounds is that your religion is changing the society in a bad way, so we need to look at that. Our society’s concept of virtue and morality is wrong. We look at women as goddesses, mothers or sisters, on the one hand; or as prostitutes. But we need to see women as individuals. If we start doing that, we will begin to think about their ‘human’ rights. This male-dominated society thinks it respects women — and women help to propagate that idea as well — but what is that respect based on? All these rules about what women should do and how they should behave are decided by a society dominated by men.

Your film is bookended by two documentary-styled sequences of a religious celebration. How did you decide on that?

I had a clear-cut idea about how I wanted the film to begin and end. In those scenes, you watch how young men are sacrificing their bodies to be literally hooked on to the vans that are used in religious processions, or how they pierce an arrow through their cheeks. If one can inflict that much violence upon oneself, it can’t be too hard to become violent towards others, can it? The idea of sacrifice might appear to be non-violent, like going on a fast, but it is an act of violence against your body. When virtue is associated with sacrifice, it can create a lot of problems in society.

You shot this film without a script or a screenplay. How did you go about it?

I feel that commercial cinema and art cinema are different. The latter is like poetry, and I work on that. If you capture that energy, it’s okay, you don’t necessarily need a resolution or conclusion to your work. That’s my goal. I’m not going to be a commercial filmmaker, I’m an art filmmaker. I think that when one has a script, or creates a certain kind of character, it is to make sure that the film targets one kind of audience. I have a vision about what I want to say, and I’m not concerned whether it hits a particular audience in a particular way or not. All of us don’t need to be on the same page.

I want to talk about subjects and leave things open-ended in my films. It is up to the viewer to come up with back stories for my characters, to think of their motivations and compulsions. I don’t care so much for the detail, I want people to talk about the situation Durga is in, the actions of a few men and the consequences. And, sometimes, about our inactions, which turn out to be more harmful to others.

Did you name it Sexy Durga because that is how she is perceived by the men around her?

Yes. She’s objectified from the very beginning, and it is because of the way men think about women. They think she’s running away with a guy, late at night, so there’s something not right about her, or that she’s available to them as well. It doesn’t matter that her name is the same as the goddess whose idol is on the dashboard — before and after knowing her name, their behaviour remains unchanged. There are other men on the road as well, and all of them think that they are helping Durga and her partner, but they are doing the opposite. But like I said, it doesn’t matter if the characters are real or not, they are not meant to be taken literally because they are metaphors for me. It’s part of the poetry.

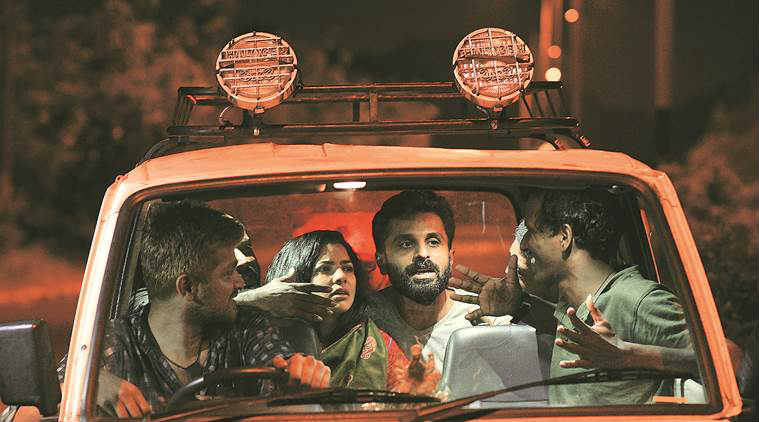

A still from S Durga.

A still from S Durga.

You pulled out of the International Film Festival of Kerala (IFFK) for putting your film in a category called ‘Malayalam Cinema Today’. Comment.

In Kerala, a lot of people are making films today, and slowly, they are being recognised outside of the state as well. The IFFK has a part to play in that success as well — people started watching different films at the festival and were provoked to make their own. But when it comes to picking films for the festival, the IFFK is ignoring these small groups of filmmakers. The programme is full of commercial films; these indie titles are lumped into a side category, which is what ‘Malayalam Cinema Today’ is. I’d be fine with that category if it were for niche films, but it has commercial releases that have run in the theatres for weeks. The IFFK does not understand the difference between indie cinema and art films, and that does not help either type of cinema.

What do you plan to do about it?

I’ve not only pulled my film out of the festival but I will have a mainstream release for it. With my last two films, I travelled across Kerala in a cinema cab with a projector. I’m not making films for festivals only. If I don’t get a theatrical release, I’ll travel with the film to different places and screen it. The IIFK is a platform but I don’t need it. I’ve finished this film under Rs 20 lakh; people in Kerala are making films with less, so there is a revolution. By not giving us the recognition we have earned, the IFFK is diluting our success, and in turn, their success.

Before the film began at MAMI, the screen was full of laurel leaves of different festivals. Is this your most viewed and most travelled film?

Yes. I learned from my experience with my second film, Ozhivudivasathe Kali (An Off-Day Game) in 2015. It’s a film I like much more than Sexy Durga. A lot of people liked it but it didn’t go anywhere. I released the film at MAMI that year in the India story section, but it went unnoticed. It was in IFFK’s Malayalam section, too. Then, there was a run at Goa Film Bazaar where many people watched it and appreciated it; there was talk of entering it into different festivals but nothing came of it.

When you make a film, you have to ensure its future — when you see lesser films than yours on big platforms, you feel sorry for yourself. So, I decided to strategise with this film. I was waiting for Cannes and Berlin, but then Rada Sesic of the International Film Festival Rotterdam got in touch with me. She had heard about the film from the Goa Film Bazaar and watched it. She invited me to enter it into the competition. Then it won the Hivos Tiger Award, and the film began to travel. I felt vindicated.

What are you working on now?

I’m working on my new film, Unmadiyude Maranam. I’m presenting that film at the Busan International Film Festival. I began working on the idea of the censorship of dreams from the Sexy Durga issue. This experience has shown me that there is a societal censorship at work that tells you not to speak of certain things or think in a certain way. Today, I feel that our government and this society wants to look into our lives in the most invasive way — what are you eating, what are you thinking, who are you sleeping with, what are you going to do? So now, even your subconscious is affected, and so are your dreams.

Photos

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05