“You look like a ripe banana; if the boys here see you, they will eat you up without even removing the peel,” Suresh Gopi’s character tells Khushboo’s in one scene in helmer Jomon’s Yaadhavam (1993), showcasing Malayalam screenwriter-director Ranjith’s knack for using metaphors to objectify the female lead and have the hero issue what amounts to a rape warning. This is just one of the many, many dialogues and moments one can find in movies penned by Ranjith — who was recently booked in two different cases of sexual harassment following the release of the Justice Hema Committee report — that are outright outrageous owing to their elitist, patriarchal and/or misogynistic tones.

Despite penning some of the most problematic screenplays in the history of Malayalam cinema, Ranjith has often portrayed himself as a champion of leftist and progressive ideals, which won him favour with the Communist Party of India-Marxist (CPI-M) — the largest party in Kerala’s ruling Left Democratic Front (LDF) — eventually earning him the post of chairman of the government-run Kerala Chalachitra Academy (KCA). However, the allegations of misconduct led to his resignation from this post. After stepping down, Ranjith made the ‘intriguing’ claim that right-wing groups had been targeting him since he became academy head, indirectly suggesting that even the allegations might be part of that campaign. Even though Ranjith has consistently stirred controversy through his films, speeches and interviews — many of which reflect anti-leftist sentiments — both the CPI-M and its Cultural Affairs Minister Saji Cherian initially backed him when the accusations first surfaced, highlighting the influence he has gained within the ‘progressive’ circles. Yet, a closer look at his films underscores his troubling politics, which, when viewed through the lenses of caste, gender and class, align with the oppressors rather than the oppressed.

Cinema Anatomy | The Mammootty that KG George saw: A versatile actor, whose actions led to his mentor’s sudden exit from cinema

Comedy drama era

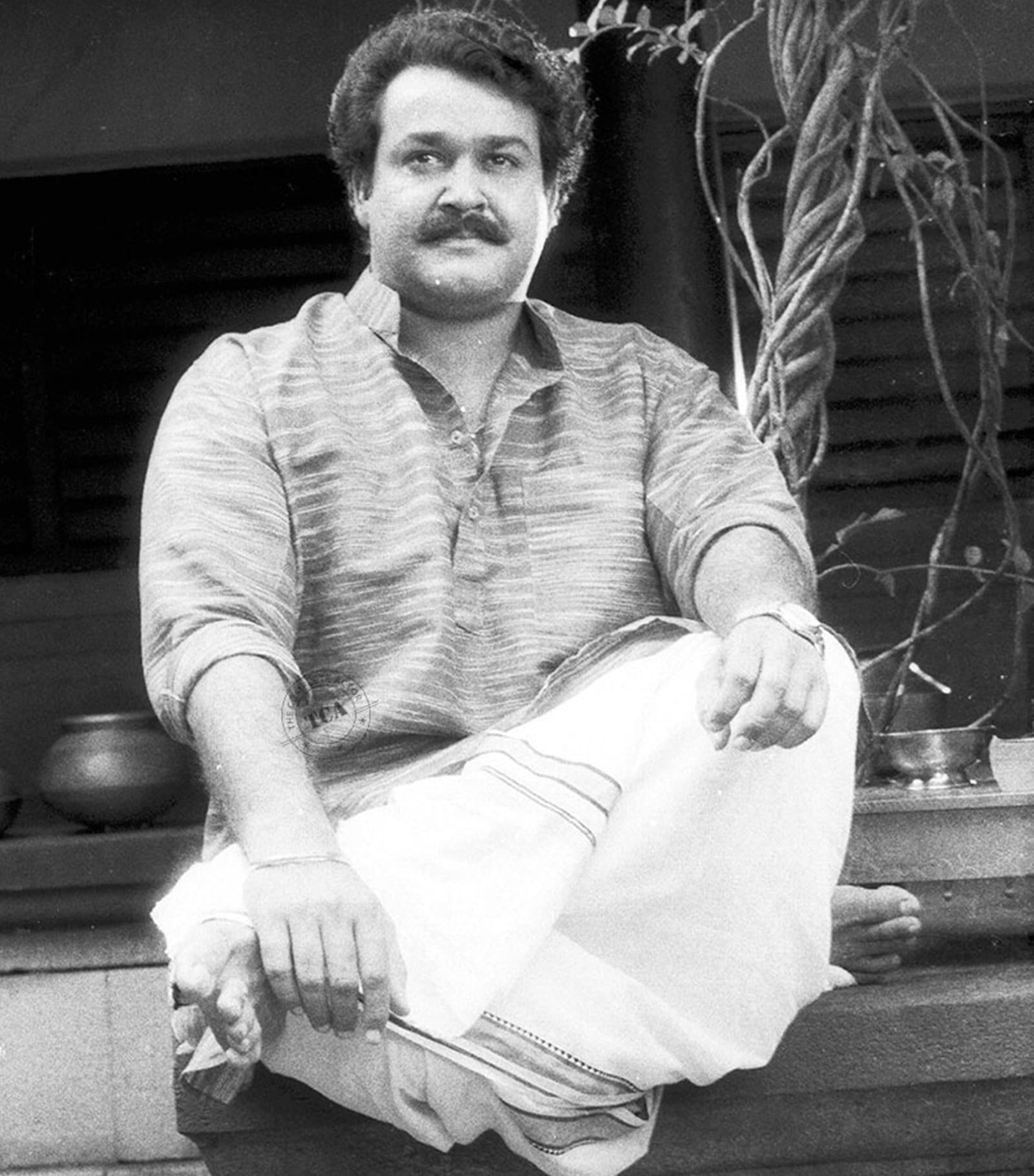

One of the most ‘celebrated’ screenwriters in Malayalam cinema, with many blockbusters to his name, Ranjith played a key role in establishing Mohanlal as an unparalleled superstar. Interestingly, Ranjith’s entry into cinema was not as a writer but as an actor, playing a small role in Ezhuthapurangal (1987). Nonetheless, Ranjith’s friend, producer Alex I Kadavil, soon recognised his potential and encouraged him to pen a story, which became his debut movie, Oru Maymasa Pulariyil (1987). It was, however, writing the story for director Kamal’s Mohanlal-starrer comedy-drama Orkkappurathu (1988) that gave him his big break, as the movie emerged as a blockbuster. Orkkappurathu also marked the first of his many collaborations with Mohanlal, who had already risen to superstar status with hits like Rajavinte Makan (1986) and Irupatham Noottandu (1987).

The success of Orkkappurathu gave Ranjith the confidence to create more comedy dramas, which soon became his thing. Most of his subsequent films in the genre were set in rural settings or small environments, focusing on average heroes and the unexpected events in their mundane lives, often featuring Jayaram in the lead role. Movies such as Pradeshika Vaarthakal, Peruvannapurathe Visheshangal, Pavakkoothu, Nanma Niranjavan Srinivasan, Nagarangalil Chennu Raparkam, Georgootty C/O Georgootty and Pookkalam Varavayi helped him establish himself as a bankable writer. However, since Malayalam cinema had no shortage of such talents, Ranjith remained just one among many.

But his first association with hitmaker IV Sasi for the Mammootty-starrer Neelagiri (1991) changed Ranjith’s career as it led him to explore new territory and begin mastering the art of creating fanservice films utilising and amplifying the traits people love about the stars. In Jayaraj’s Johnnie Walker (1992), his hero was a handsome middle-aged man who joins a college, and who better to pull off such a role than Mammootty, known for his good looks and physique?

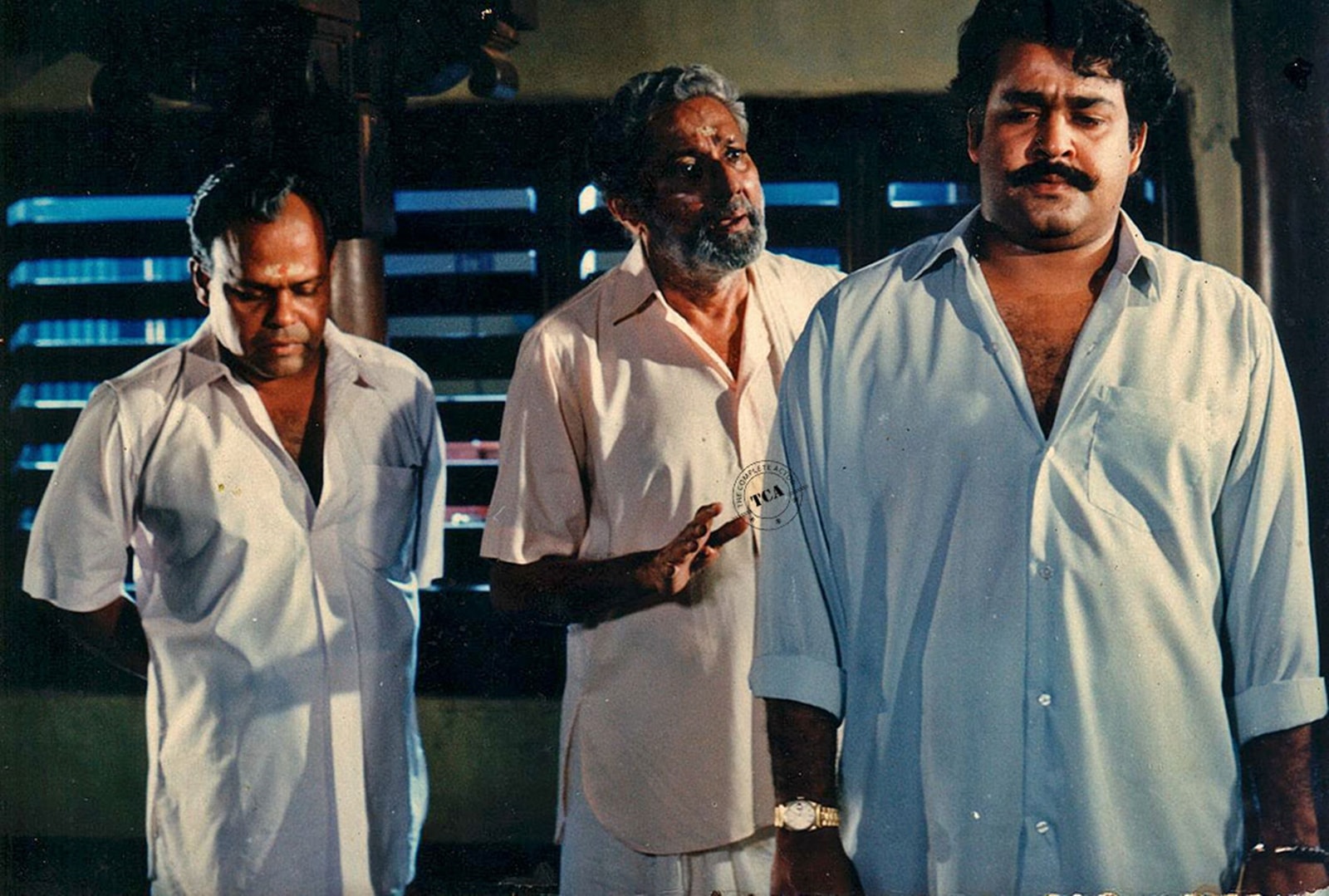

The savarna, misogynistic hero who remains free of labels

Ranjith’s shift in direction could not be more evident and clear as he penned Devaasuram (1993) for Sasi, one of the most elitist and misogynistic Malayalam films of all time, celebrating toxic hypermasculinity through superstar Mohanlal. Based on, according to Ranjith himself, a real-life person named Mullasserry Rajagopal, Devaasuram revolves around Mangalassery Neelakandan (Mohanlal), an alcoholic, womanising wealthy man who isn’t labelled a habitual criminal solely because of his feudal background, reflecting Kerala and the makers’ un/conscious casteist mentality. Despite his profligacy bringing him to the brink of bankruptcy, Neelakandan’s elitism and caste pride remain unshaken. He only respects “good artists and good rowdies.” While Neelakandan’s associate, Warrier (Innocent), refers to the women Neelakandan has been involved with as concubines and sluts, Neelakandan himself is spared such derogatory labels. Although he prides himself on being a good fighter, he recruits a financially disadvantaged Christian goon to help him beat Mundakkal Kunjikrishnan Nambiar (Janardhanan), the patriarch of a rival family. To maintain his masculine image, Neelakandan justifies this by claiming that Nambiar lacks the quality to be defeated by him. In another scene, Neelakandan becomes agitated when a Muslim NRI, the son of a former worker at Mangalassery, shows interest in buying a piece of land he has for sale. He insists that only someone with “value” should buy it, implying that only a savarna person is worthy. Even if it could be argued that these merely show how vile Neelakandan is, the film’s portrayal of him taking pride in learning that his real father is a savarna man — thus getting over the sadness created by the knowledge that his supposed father was not — underscores the film’s casteist tones.

Story continues below this ad

Mohanlal with Innocent and Jose Prakash in Devaasuram. (Image: The Complete Actor website)

Mohanlal with Innocent and Jose Prakash in Devaasuram. (Image: The Complete Actor website)

In Ranjith’s films, the links between savarna identity, hypermasculinity and misogyny are inseparable. As elite as Neelakandan is, he also embodies toxic masculinity and a fragile male ego. When he learns that his friends have been disrespected by dancer Bhanumathi (Revathi), he hatches an elaborate plan to humiliate her publicly, leading her to quit dancing. Upon realising her potential, he attempts to apologise, but in his feudal way of not saying the actual words. Bhanumathi’s firm rejection of his apology impresses Neelakandan, who then praises her resilience, saying, “Here is a real woman; the ones I had seen till now were corpses.” The lack of remorse with which Ranjith included such dialogues reveals the depth of misogyny in his writing. Yet, when Neelakandan begins to face consequences for his wrongdoings, Bhanumathi is shown to rush to his aid, forgiving him — reflecting the Brahminical culture where women, sacrifice and forgiveness are intertwined. Even in the end, it is the woman who is kidnapped by the villain to seek revenge on Neelakandan.

However, the performances, particularly Mohanlal’s, turned the movie into a blockbuster with it being regarded as one of his most beloved movies. The approach used by Ranjith and Sasi was straightforward: capitalise on Mohanlal’s popular traits and give him ample space to perform, while adhering to elements appealing to an elite male audience. In Devaasuram, Mohanlal is presented as the epitome of Malayali masculinity — dressed in mundu, with a twirled moustache, wavy hair and firm physique — enhanced by the glorification of his caste identity, his violent acts, and his deep-rooted sexism; and this portrayal resonates with a mass audience. Devaasuram also marked the beginning of a series of films set in Varikkasseri Mana, an old Namboothiri mansion..

Mohanlal and Revathi in Maya Mayooram. (Image: The Complete Actor website)

Mohanlal and Revathi in Maya Mayooram. (Image: The Complete Actor website)

It took Ranjith no time to realise what sells in Kerala and the self-proclaimed former member of the Leftist Students’ Federation of India (SFI) quickly began writing a slew of movies for superstars, filled with hypermasculinity, objectification of women, and misogyny. He glorified these elements to such an extent that viewers would clap and cheer at every such moment as he fully utilised his skill in crafting sharp and rhythmic dialogues. Even in his quieter dramas like Maya Mayooram and Krishnagudiyil Oru Pranayakalathu, Ranjith included at least one instance of manipulation, gaslighting or victim-blaming to leave his signature male-centric mark. His action films like Rudraksham, Rajaputhran and Asuravamsam, on the other hand, celebrated machismo by portraying central female characters falling for emotionally unavailable men, who showed no remorse in being violent — suggesting that women are only attracted to men who could potentially harm them in a conflict.

Ranjith returned to his comfort zone of Varikkasseri Mana in 1997 by writing Aaraam Thampuran for Shaji Kailas, another film that banked on Mohanlal’s star aura, savarna aesthetics, and misogyny, becoming a blockbuster due to the performances, particularly by Mohanlal and Manju Warrier, and its music. Another skill of Ranjith is his ability to deceive viewers into thinking his female characters are strong, thereby making him seem less problematic than he is. In Aaraam Thampuran, we are introduced to Unnimaya (Manju Warrier) as a bold, courageous, and independent woman. However, when the time comes for her to stand up, her character becomes shallow, overshadowed by the male lead, waiting for him to save her. Despite her initial portrayal, once she falls in love with Jagannadhan (Mohanlal), the new lord of Kanimangalam mansion, Unnimaya becomes like a cat curled up on his lap, barely saying anything. Even other women in the film like Subhadra (Srividya), the villain’s sister, live under the grace of men. The only self-sufficient woman, Nayanthara (Priya Raman), Jagannadhan’s friend, meanwhile, is slut-shamed not by anyone else but by Unnimaya herself and these artistic choices are undoubtedly problematic.

Story continues below this ad

Mohanlal in Aaraam Thampuran. (Image: The Complete Actor website)

Mohanlal in Aaraam Thampuran. (Image: The Complete Actor website)

His two subsequent blockbusters — the Mohanlal-starrer Ustaad (1999) and the Mammootty-starrer Valliettan (2000) — also featured strong, all-powerful heroes, with women playing minimal roles as their romantic interests. Even in Summer in Bethlehem (1998), which has five women at the centre of it, it was ultimately the men who steer the narrative.

“On those nights when I return home, drunk and unsteady, to kick for no reason; to make love under one bedsheet on rainy nights; to give birth to and raise my children; and to beat her chest and cry when I die and my body is burned, I need a woman. If that’s possible, get in the car.” Note the emphasis on the word “woman” here as Induchoodan (Mohanlal) implies that women who don’t meet these criteria aren’t real women. This also echoes Neelakandan’s problematic views, right? Could one believe that this, one of the most misogynistic dialogues ever, is from one of the biggest blockbusters in Malayalam cinema history? Directed by Shaji Kailas and written by Ranjith, Narasimham (2000) solidified Mohanlal’s status as the undisputed superstar of Malayalam cinema, as he perfectly embodied the archetypal toxic hypermasculine man. Out of all the ways Ranjith could have written a proposal — literally millions — choosing such a problematic approach for the lead character, glorified and celebrated up to that point, to propose to the woman at the film’s end encapsulates everything wrong with his movies. Given Narasimham’s impact on the Malayali psyche, with Mohanlal’s mundu (dhoti) becoming a trendsetting product, it’s not far-fetched to suggest that such problematic representations may have influenced the men of the state.

Mammootty in Valliettan. (Image: Matinee Now/YT)

Mammootty in Valliettan. (Image: Matinee Now/YT)

For a moment, let’s assume that in Devaasuram, Ranjith was merely portraying Rajagopal’s life and events almost biographically. Then how would he justify its sequel, Raavanaprabhu (2001), which marked Ranjith’s debut as a director? If Devaasuram is problematic, then Raavanaprabhu is problematic ultra max pro. If Neelakandan is a hypermasculine man with a fragile ego, his son Karthikeyan is a shameless criminal who would even go so far as to kidnap his rival’s daughter to win back his ancestral home. From body-shaming and objectifying women to using sexist cuss words at every juncture and promoting armed revolution, Karthikeyan is equipped with all things problematic. But Ranjith doesn’t stop there; even supporting characters like SP Sreenivasan Nambiar IPS (Siddique) and Mundakkal Rajendran (Vijayaraghavan) are given utterly vile dialogues under the guise of showing that they are “raw men.”

Melodramas with female leads where women do nothing but cry

However, after gaining a foothold with Raavanaprabhu, Ranjith began shifting focus slightly, penning story-oriented dramas instead of fanservice vehicles. Three of these movies — Nandanam (2002), Mizhi Randilum (2003), and M Padmakumar’s Ammakilikkoodu (2003) — featured women as the main protagonists. However, if you thought Ranjith had finally begun making women-centric movies, you couldn’t be more wrong, as all these films depicted stories of powerless women, destined to face unhappiness alone in life and be perpetually sad or crying, almost as if he knew viewers would love melodrama portraying women’s sufferings. Meanwhile, in Black (2004) and Chandrolsavam (2005), though the women had identities, they were closely linked to the men and inseparable.

Story continues below this ad

Kaiyoppu (2007) was arguably his first movie wherein he treated women with respect. A simple drama about the rekindling of lost lovers, Mammootty and Kushboo blended into the tale, delivering a touching tragedy. He nevertheless continued writing fanservice movies, probably for money or due to requests from friends, and all of these, though different from the ’90s male chauvinistic movies, carried no sympathy for demeaning women.

Mohanlal in Narasimham. (Image: The Complete Actor website)

Mohanlal in Narasimham. (Image: The Complete Actor website)

His first and only women-centric movie, Thirakkatha (2008), which earned the National Film Award for Best Feature Film in Malayalam, deserves praise for the respect with which he handled the character Malavika (Priyamani), a yesteryear superstar whose life took a major downfall. However, the story’s credit can’t go completely to him, as it was heavily inspired by the life of Srividya or many others, regardless of his claims.

Rape joke in Spirit isn’t as harmless as he has said over the years

Later, his direction in Paleri Manikyam: Oru Pathirakolapathakathinte Katha (2009) also received praise, especially for its presentation of the villains; un/surprisingly, in a movie that revolves around a case presented as the first rape and murder registered since Kerala’s formation in 1956. His films such as Pranchiyettan and The Saint (2010), Indian Rupee (2011), and Spirit (2012) mostly had token female characters. Making Kaiyoppu or Thirakkatha did not change him in any way, as exemplified by the rape joke in Spirit. “Good that I stopped drinking, otherwise I would have raped you,” says Raghunandan (Mohanlal) to his ex-wife casually.

Ranjith with Mohanlal on the sets of Raavanaprabhu. (Image: The Complete Actor website)

Ranjith with Mohanlal on the sets of Raavanaprabhu. (Image: The Complete Actor website)

Spirit, un/fortunately, became his final success and his subsequent movies like Kadal Kadannoru Mathukkutty (2013), Njan (2014), Loham (2015), Leela (2016), Puthan Panam (2017) and Drama (2018) left theatres without creating any impact. Since then, he has been working as an actor, and the first time a movie helmed by him came this year, as he directed a segment in the anthology streaming series Manorathangal.

Story continues below this ad

‘Won’t apologise for my characters’

“I don’t see a situation where I need to apologise. Either it’s a particular character’s nature or a harmless joke. It’s not misogyny, neither am I a person who goes around attacking women,” Ranjith told Times of India in 2018. Every time journalists have raised the topic, he has brushed it off, saying that these are just characters and noting that even legends made such grey-shaded ones. However, in Ranjith’s movies, all of these characters are portrayed as ultra-glorified heroes who stand as the epitome of masculinity and elitism, and that’s not something to be neglected easily.

Despite his films being called out by a large portion of the population over the years for peddling savarna and misogynistic notions, CPI-M appointing him as KCA chief came as a shock to many. And even after being accused of misbehaviour, the initial support he got from the party and government was suspicious since it’s disappointing to see a leftist party backing a filmmaker who has made many problematic films throughout his career and banding behind him even after being accused of major crimes.

Mohanlal with Innocent and Jose Prakash in Devaasuram. (Image: The Complete Actor website)

Mohanlal with Innocent and Jose Prakash in Devaasuram. (Image: The Complete Actor website) Mohanlal and Revathi in Maya Mayooram. (Image: The Complete Actor website)

Mohanlal and Revathi in Maya Mayooram. (Image: The Complete Actor website) Mohanlal in Aaraam Thampuran. (Image: The Complete Actor website)

Mohanlal in Aaraam Thampuran. (Image: The Complete Actor website) Mammootty in Valliettan. (Image: Matinee Now/YT)

Mammootty in Valliettan. (Image: Matinee Now/YT) Mohanlal in Narasimham. (Image: The Complete Actor website)

Mohanlal in Narasimham. (Image: The Complete Actor website) Ranjith with Mohanlal on the sets of Raavanaprabhu. (Image: The Complete Actor website)

Ranjith with Mohanlal on the sets of Raavanaprabhu. (Image: The Complete Actor website)