Click here to follow Screen Digital on YouTube and stay updated with the latest from the world of cinema.

Dark Side of the Moon

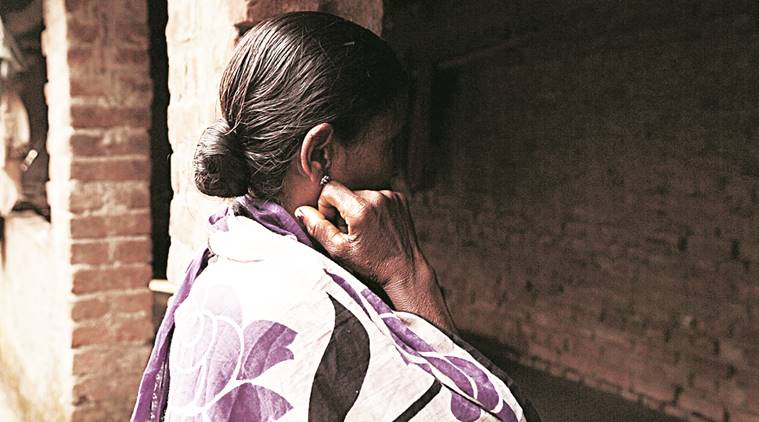

As the supernatural takes over the small screen, a new documentary turns the spotlight on women who are branded as witches

Stills from Some Stories around Witches; (bottom) filmmaker Lipika Singh Darai

Stills from Some Stories around Witches; (bottom) filmmaker Lipika Singh DaraiA winding dust track leads to a village in Odisha that complies with rural stereotypes — a kachcha house with terracotta-tiled roofs, a charpoy laid out in the courtyard, skinny children at play, cows going home, a rooster crowing. A few years ago, a teenage girl from the village went to the police station holding the severed head of her sister’s mother-in-law, surrendered, and fell down unconscious. The old woman, she said, was a witch. The picture of her holding the head was published in newspapers and that was how filmmaker Lipika Singh Darai “met” Niru for the first time and started a journey that has culminated in a film, Some Stories around Witches.

Documentary fans associate Darai with films rooted in a slice of her life. Darai, a graduate from the Film and Television Institute of India (FTII), who returned her three National Awards to protest the appointment of Gajendra Chauhan as FTII chairman, is capable of raising the personal to a socio-political height. Some Stories around Witches is a nuanced exploration into one of India’s darkest social realities. Presented by Delhi-based Public Service Broadcasting Trust, the film comes at a time when family dramas on primetime television perpetrate the cult of the daayan, ichhadari nagin and the panoply of fantastical beings who are fuelled or fought by chants, charms and magic potions.

[related-post]

“Witch stories from my childhood were always sensational. After seeing Niru’s situation and that of a few others closely, the meaning of those old stories has changed completely,” says Darai in a voice-over. The filmmaker travelled through the Mayurbhanj and Keonjhar districts of Odisha, investigating cases of witch hunting. Though she focuses on her home state, the film is descriptive of realities existing elsewhere in India. “There are 11 states where such cases are happening every day. The Odisha Prevention of Witch-Hunting Act was passed in December 2013 and there is an attempt to make this a national law,” says Darai.

Lapika posing for the camera.

Lapika posing for the camera.Some Stories around Witches unfolds as a linear narrative, formed into chapters, titled Niru, Electric Pole and Chicken Meal. The victims of Electric Pole are several members, including a man, from a family though it was a 60-year-old woman who was stripped and tied to a pole at the centre of the village and physically tortured in 2014. “In other parts of the country, it is mostly women who are branded as witches. In Odisha, men are also targeted and, sometimes, entire families are accused,” she says. Another family is at the centre of Chicken Meal. The villagers suspected them because their harvest was too good to be true. When the family cooked chicken during a community prayer to cleanse the village of evil, they were ostracised and fined Rs 20,000.

Darai talks about an evening in Odisha when she was a child. “A truck passed by with two ‘witches’ who had been caught. I have a blurred memory of two dusty bodies of women standing in the truck surrounded by men. I remember thinking that it was fortunate that they did not jump out of the truck and come into our village,” she says. Another time, she was ill and somebody suggested that “I was possessed by a spirit and it was a woman. There was a strong question in my mind — why a woman?” In Some Stories around Witches, she makes in-roads into her own family history. Against visuals of her father in a hospital bed, she narrates, “One by one, there had been unnatural deaths in my father’s family. People say his ancestral property is cursed. Now, it is my father’s turn and then, it will be mine.”

As the film focusses on the perpetrators, a village ward member in Chicken Meal says, “We made a rule. How can we stay united without rules? That is why we issued a fine of Rs 20,000.” But, it is the “witches” whose voices, brimming with pain, emphasises the gravity of the problem that is ignored by mainstream discourse. Moumita, a little schoolgirl, tells the camera, “They say I turn into a cat, I am a witch. I don’t say anything.”

This has been the filmmaker’s most excruciating project. It was seven months after the incident in Electric Pole that Darai met with the 60-year-old victim. “She spoke as if she had never spoken about it, never had a real conversation. She had answered the queries of the police and other authorities but never could open up, I felt,” says Darai, adding, “I felt a deep acceptance within her as if it could happen to any woman, which was also helping her recover. That feeling shook me. I wonder if a woman can truly recover from such a situation.”

Darai says she couldn’t edit the film for one or two months, couldn’t face the rushes. The film ends with Darai and Niru on a beach. “When I asked Niru how she felt seeing the sea for the first time, she said it was like a huge river but directionless,” says Darai.

Photos

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05