Click here to follow Screen Digital on YouTube and stay updated with the latest from the world of cinema.

In a Woman’s Hands

Better known as a writer of poetry, novels and plays, Annie Zaidi explores the genre of women’s literature in India through a short film, titled In Her Words.

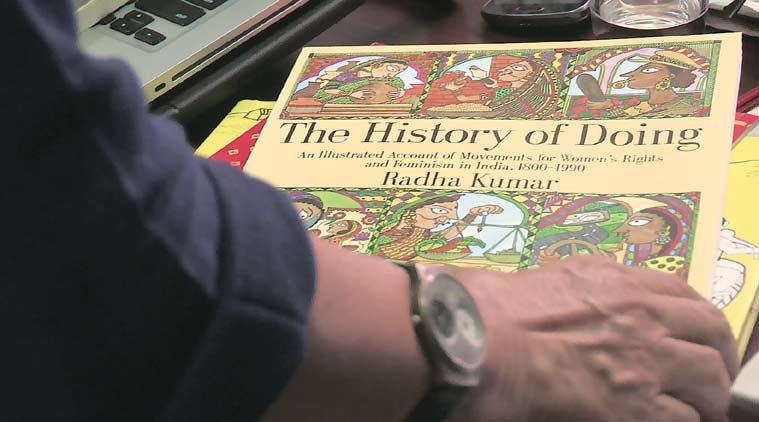

Mridula Koshy was filmed in a jungle park where she sees a lot of stories.

Mridula Koshy was filmed in a jungle park where she sees a lot of stories.Annie Zaidi was reading through 2,000 years of women’s writing from India for an anthology, titled Unbound (2015), when an impossible idea struck her. She decided to make a film exploring the “historic and social journeys of Indian women’s lives as revealed through the literature they created in every era”. In Her Words, made this year and screened at Open Frame, a film festival by Public Service Broadcasting Trust, navigates through essential episodes of women’s literature in India, such as the impulses of religion and the Partition. The hour-long narrative unfolds through conversations with contemporary writers, publishers and scholars, from Urvashi Butalia to Kiran Nagarkar. Excerpts from an interview with Zaidi:

A film on literature involves translating a medium of words into a medium of visuals. Why did you choose to explore this as a film rather than an essay?

I had been researching women’s writing for Unbound. As I was reading, I found myself intrigued by and enriched with a new sense of feminine (and feminist) history in India. It is significant for the same reason that any history is significant — what our ancestors did, who overcame whom, and how the rules of life changed. But, as a little girl, I never had any sense of the feminine in our history. A few queens’ names were tossed in, often in the martial context (Lakshmibai, Sultan Razia etc). It was when I read the works of women that I began to see the lives of Indian women through their eyes. Those who read a lot will probably have some sense of this history but I wanted to focus on the historical aspect of women’s lives as seen through our literature. I also wanted it to be accessible to a wider audience, including those who may not read that much. Film was a good way to do it.

Women’s writing in India is a broad spectrum. How did you pack this into one hour?

It would have been hard for me to pack all of that history in even two or three hours. I think I did well by interviewing the people in the film. I looked for a mix of historians, researchers, translators, editors, publishers and writers. They could talk me through the historical highlights.

A still from the film.

A still from the film.Why do women write as opposed to why men write?

I can’t say that there is a difference between ‘why’ women write vis-a-vis why men write. I’m guessing the essential motivations are the same — a desire to express yourself, or to document what’s happening in your life and times, or to build empathy with other people around, or to challenge society in some fashion, or to protest some injustice. It’s more the ‘what’ that’s different. Women’s lives — external and internal — and their perspectives on any aspect of human existence may be different, depending on what their experience of life has been.

Annie Zaidi

Annie ZaidiThe film refers to works that are available on mainstream English-language bookshelves. Why don’t we see the less-known vernacular writers?

I left it to my interview subjects to bring up books they felt they needed to refer to in the course of the conversation. I didn’t interfere too much with that. There are many regional writers in the film, included both visually and orally, and many languages represented. There are references to Mahasweta Devi, Mirabai, ancient Pali texts, Muddupalani, Ismat Chughtai, Shivani and Maitreyi Pushpa. They’re from all over the country. Many different languages.

About less-known writers… Two things to consider. I don’t know if mentioning less-known writers (simply because they are less known) would serve a purpose, given that this film was never going to be a detailed history inclusive of all known writers. Even very well-known writers were not mentioned and that was fine, too. Secondly, there are writers whom one would not call ‘well-known’, certainly not mainstream. Urvashi Butalia talks about Radhaben Garve, for instance, and reads a passage from Baby Haldar’s book. Uma Chakravarti reads out a translation of an ancient Tamil verse. It’s actually pretty diverse.

Why don’t we see you in the film?

I decided that this film was not going to be about me, at least not directly. I have many, many concerns but I’m in it in the sense that I’ve chosen what to film, who to talk to, what parts of the conversation to include. Many conversations lasted several hours. I picked out what I felt was most critical. So, in a way, all of it is a summary of my own concerns.

dipanita.nath@expressindia.com

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05