Click here to follow Screen Digital on YouTube and stay updated with the latest from the world of cinema.

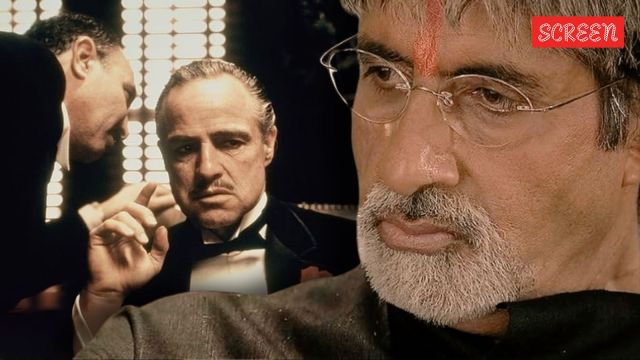

In Sarkar’s opening scene, Ram Gopal Varma crafts a legend as deep and fierce as Francis Ford Coppola’s Godfather

Opening Act: In the opening scene of Sarkar, Ram Gopal Varma plays with the conventions of filmmaking, establishing himself as a director unafraid to defy norms and challenge cinematic tradition.

Ram Gopal Varma's Sarkar is much more than just a homage to The Godfather.

Ram Gopal Varma's Sarkar is much more than just a homage to The Godfather. If it were left to you, how would you depict power on screen? This is the question that sits at the centre of the opening scene of Ram Gopal Varma’s Sarkar. On the surface, yes, it mirrors the opening of The Godfather. The bones of the scene are the same. A man wronged. A daughter defiled. A plea to a feared don. But that’s the thing with surface readings, they hold your hand just long enough to get you somewhere familiar, but they rarely guide you beyond. They let you recognise, but not necessarily resonate. Look again. Watch how Varma conceptualises, composes, and cuts. It is not just reverence, it is reinterpretation. It is not just homage. It is authorship.

The deepest difference between the two scenes lies in the way they are dreamed. Coppola imagines his world with restraint. The camera seldom intrudes. It lingers in long takes, steady and watchful, only breaking to catch a flicker of reaction. The room is dim. Don Corleone’s domain wrapped in shadows. The air pressed down with the weight of silence. Every pause speaks. And when Marlon Brando says, “You don’t offer me friendship. You don’t even think to call me Godfather,” something intensifies. It’s not anger. It’s something deeper. Disappointment braided with dominance. So Coppola doesn’t show power. He lets you feel it, close, almost uncomfortably so. But Varma steps away. His gaze diverges, disobeys, and in doing so, he creates a legend of his own.

Its starts with the father, (Virender Saxena), stepping out of an auto and walking, quietly, all the way into the mansion where Sarkar (Amitabh Bachchan) lives. And in that walk, before Sarkar even appears, the world around him begins to speak. Outside, a long line of devotees stands, waiting, patient, forming a queue that stretches along the gate. Inside, men with guns stand alongside those in khadi and kurta, all drawn here. And in a glance, we understand: whoever Sarkar is, he is the one everyone needs. Bodybuilders lift iron in silence, guards move like they serve someone more than just a man. But it is through the father’s eyes that we truly see it. His gaze wide, stunned, caught between disbelief and hope. He walks slowly, as though the weight of his losses clings to his steps. And yet, with each footfall into this strange and powerful place, something shifts. As if, just maybe, in this house, he might find something left to hold onto. Something that hasn’t yet turned away.

What Varma adds, as the final stroke, the cherry on top, is the voiceover. Long, steady, running beneath the entire sequence like a current. And even, at one moment, he bends the form, the voiceover blends into real speech. It’s seamless. It’s bold. Here was a filmmaker not afraid to break the rules. Yes, the technique is loud, sometimes even theatrical. The Dutch angles tilt reality just enough. The lighting, pulled from German expressionism, cuts through space in silhouettes and shadows. The camera doesn’t just capture, it flies like a bird circling over Sarkar’s world. And yet, through all this style, Varma tells us exactly what we need to know. He shows us the myth before the man.

But more than anything, what Varma manages to carve out is the ache of a father, wronged, worn down, failed by the very system meant to protect him. And yet, within this space, through Sarkar, he finds that another system exists. This is where the split between Coppola and Varma deepens. In The Godfather, Don Corleone’s anger is personal, he’s almost hurt. His power demands loyalty. But here, Sarkar’s anger isn’t aimed at the man who walks through his gates, it’s turned outwards, at the world that drove him here. At the broken structure that forced this father to seek help outside the law. Sarkar isn’t raging at the plea. He’s raging at the necessity of it.

That’s what sets the two films apart: Coppola told the story of a Don, a gangster who masked revenge as justice, while Varma portrayed an outlaw, a messiah-like figure striving to restore true justice. In that sense, Varma’s film is actually a reimagining of the angry young man. In the opening scene, there are hardly any words given to Bachchan. Just a tight close-up. Just his eyes. But within them, you see it all, the same anger that once burned through cinema, now simmering under silence. That is the real strength of this beginning. It starts as a portrait of power, but by the time it ends, it has become a portrait of authority born out of rage, carved by betrayal, steadied by time. When they talk about Sarkar, they talk of Coppola, of The Godfather, or even Balasaheb Thackeray. But in truth, it was always a tribute to the fury that helped make Bachchan one of the greatest movie stars this country has ever known.

Opening Act is a column where Anas Arif breaks down some of the greatest opening scenes in film and television.

Photos

Photos

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05