Click here to join Express Pune WhatsApp channel and get a curated list of our stories

A letterbox with a crown and 2 stones for elephants, Pune’s GPO has many tales to tell

First built in the 19th century, the Pune General Post Office has, over the years, witnessed the growth of the postal service in India – from ‘Dawk’ to digital.

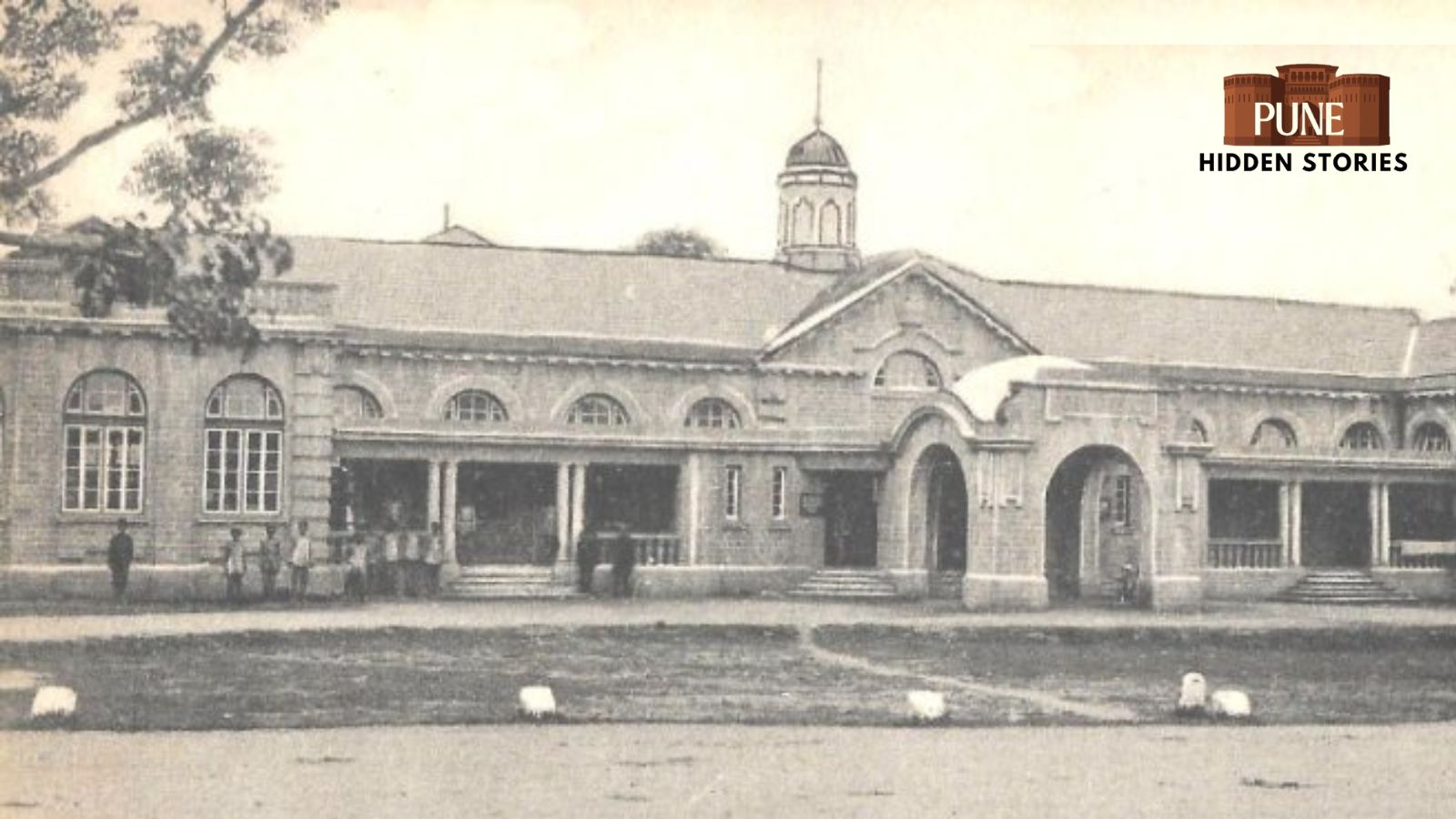

The building, as it stands today, is the expanded version from 1928. (Credit: Internet Archive)

The building, as it stands today, is the expanded version from 1928. (Credit: Internet Archive) Amidst the bustle of activity at the Pune General Post Office (GPO) – a place that people mostly visit today for works related to life insurance policies, postal savings schemes or Aadhaar card updates – it is not difficult to notice the traces of a bygone era when its function of delivering letters was of prime importance and was carried out in a manner very different from today’s.

The GPO stands as a majestic relic of the British colonial period, a time when the very services it offers today were unimaginable. The architecture of the building itself serves as a portal to a time when mail traversed the land on the backs of elephants and horses. In a quaint corner of the post office’s garden, now adorned with a coat of vibrant red paint, two weathered stones bear silent witness to a remarkable history – they once served as anchor points for the majestic elephants that bore the weight of precious mail.

All the letters sent from the letterbox with the design of the crown of Queen Elizabeth II bear a special pictorial stamp cancellation of Pune head post office, Public Relations Officer Anup Singh Nahate said.

All the letters sent from the letterbox with the design of the crown of Queen Elizabeth II bear a special pictorial stamp cancellation of Pune head post office, Public Relations Officer Anup Singh Nahate said.

The institution, although popularly called the ‘General Post Office’, is the Head Post Office and was first built in the 19th century, around 1873-1874. Postal services in Pune had commenced much before this during the rule of the Peshwas as well as later when the region fell into British hands. The building was designed and built by Colonel Finch, R.E. at a cost of Rs 19,710. Originally, the building had three rooms, (50’ by 20’), (57’ by 20’), and (16’ by 20’), and quarters for the postmaster.

The building, as it stands today, is the expanded version from 1928. A plaque installed at the GPO says the style of the building is a tribute to Andrea Palladio, a 16th-century Italian Renaissance architect. The Palladian style is a classical architectural style. Its characteristic features are the Tuscan columns in the verandah, arched windows with enlarged keystones and wedge-shaped stone, rusticated corners and typical railings balusters, parapets and high-ceilinged halls.

The Pune GPO is one of the very few letter boxes in the country with the design of the crown of Queen Elizabeth II, says Public Relations Officer Anup Singh Nahate (Express photo by Ravina Warkad)

The Pune GPO is one of the very few letter boxes in the country with the design of the crown of Queen Elizabeth II, says Public Relations Officer Anup Singh Nahate (Express photo by Ravina Warkad)

The premise also holds an intriguing historical treasure – a letter box with the design of the crown of Queen Elizabeth II on the top. As per Public Relations Officer Anup Singh Nahate, it is one of the very few letter boxes in the country that has the crown of Queen Elizabeth. “All the letters sent from this letterbox bear a special pictorial stamp cancellation of Pune head post office,” he says.

The building was declared a heritage building in 2000. It was refurbished under ‘Project Arrow’ which was launched in 2008 for quality improvement of the India Post and was specifically aimed at comprehensive improvement of the core operations, as well as the ambience in which postal transactions are undertaken. This involved getting new tiles, furniture, a new logo and a touch of red everywhere.

In a quaint corner of the post office’s garden, a red stone bears witness to a time when mail traversed the land on the backs of elephants. The stone once served as an anchor point for the elephants. (Express photo by Ravina Warkad)

In a quaint corner of the post office’s garden, a red stone bears witness to a time when mail traversed the land on the backs of elephants. The stone once served as an anchor point for the elephants. (Express photo by Ravina Warkad)

“The entire look of the GPO was changed, from colours to tiles…the colours were selected from Delhi, and this was to bring uniformity of look across all post offices in India,” says retired postmaster Sudhesh Gaikwad.

From ‘Dawk’ to post

Even before the arrival of the British, a postal service called the ‘Dak’ (later spelt as ‘Dawk’) was in existence in the region that mainly served the ruling Peshwas, connecting Pune with towns of importance in the Deccan region. It had its network of postal routes and facilities, allowing for the exchange of letters and messages within the Maratha territory.

Pune’s strategic importance as a major city in western India led to the establishment of a post office to facilitate communication and administrative functions in the region.

Soon after they took over the administration of Pune in 1818, the British established their own postal services that primarily served the administration, military, and local businesses. Over the years, the post office in Pune evolved and was completely revamped after the Post Office Act of 1854.

“Previous to 1854 the post office was a medley of services in different provinces, each having separate rules and different rates of postage. Regular mails were conveyed over very few main lines between important towns, and collectors of the districts were responsible for the management of their own local post offices. There were no postage stamps, and since rates were levied according to distance and most distances were often unknown, the position of a postal clerk in a large office was distinctly lucrative one,” as per the 1920 book Post Office of India written by Geoffrey Rothe Clark, the British administrator who headed the department for seven years.

The enactment of the Act marked a significant turning point in India’s postal services. It established a uniform postal system across India, introduced postage stamps, and standardised postal rates. With the British government taking control of postal services, the system was expanded, introducing railways and telegraph lines for faster communication.

‘Zero Stone’ and the great trigonometric survey

Just outside the post office, there stands a unique marker known as the ‘zero stone’. This stone was originally placed during the Great Trigonometrical Survey, conducted between 1800 and 1860. It served as a reference point with a known elevation relative to the mean sea level. As part of this survey, 80 similar stones were placed across the country to mark the zero points for India’s comprehensive mapping.

Despite periods of neglect over time, efforts were recently made to preserve it as a heritage monument. In 2019, a walk-through museum was established nearby, offering visitors the opportunity to explore the history of the Great Trigonometrical Survey and the significance of the ‘zero stone’ in India’s mapping and surveying heritage.

Click here to join Express Pune WhatsApp channel and get a curated list of our stories