Military Digest: From Kasauli and Ambala to Dagshai, meet the British officer behind these cantonments

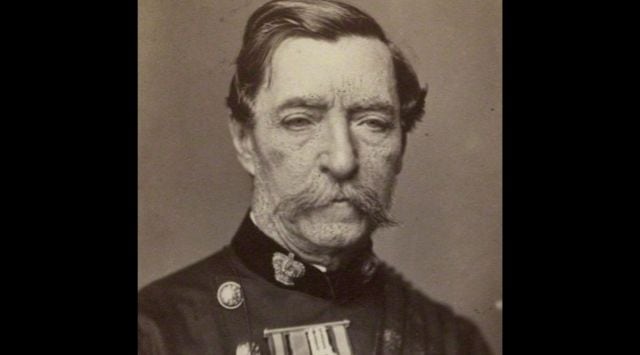

General (later Field Marshal) Robert Napier became the first from Bengal Engineers to become the Commander-in-Chief of Indian Army in April 1870.

General (later Field Marshal) Robert Napier played a key role in the First Anglo-Sikh War, Second Anglo-Sikh War, Siege of Kangra, Siege of Multan, capture of Lucknow in 1858, Second Opium War in China and Expedition to Abyssinia.

General (later Field Marshal) Robert Napier played a key role in the First Anglo-Sikh War, Second Anglo-Sikh War, Siege of Kangra, Siege of Multan, capture of Lucknow in 1858, Second Opium War in China and Expedition to Abyssinia. Exactly 152 years before General Manoj Pande became the first officer from the Corps of Engineers to become the Chief of Army Staff of India in April, an officer of the Bengal Engineers, General (later Field Marshal) Robert Napier became the first from that branch of service to become the Commander-in-Chief of Indian Army in April 1870.

Napier’s relevance for this part of the country lies in the fact that four cantonments in the northern region were designed by him. Then a Captain, Napier laid out the cantonments of Ambala, Kasauli, Dagshai and Subathu. Another key cantonment that was laid out by him is Darjeeling. At a time when the cantonments in India are on the chopping block and may soon be a part of history, it is worth going back to those days and individuals who were responsible in setting them up.

The period of time through which Robert Napier served in the Indian Army was quite tumultuous and he played a key role in almost all major events and battles. These include the First Anglo-Sikh War, Second Anglo-Sikh War, Siege of Kangra, Siege of Multan, capture of Lucknow in 1858, Second Opium War in China and Expedition to Abyssinia.

Robert Napier’s initial intention was to join the Royal Artillery, where his late father had served. However, his uncle nudged him towards passing the examination for engineers and thus at an age of 19 in 1828 he found himself serving the Bengal Sappers in Aligarh.

After a short tenure in Aligarh, he was posted to take command of a company of Bengal Sappers in Delhi in 1829. In due course of time, and after a challenging stint in the re-modelling of the Upper Bari Doab canal, Napier was directed to lay out the cantonment of Darjeeling.

His memoirs, penned by his son after Napier’s death in 1890, note that in Darjeeling his immediate duties were to lay out the new settlement and to establish easy communication with the plains 7,000 feet below. “When he first began his work, the forest was so dense that all he could do was to slowly grope his way from point to point and ridge to ridge with the theodolite. Having no trained assistants, he enrolled, at his own charge, a small body of Hill men whom he taught in a measure to supply their places,” the memoirs note.

In due course of time Napier was appointed the executive engineer of Sirhind Division in Punjab but his design of Darjeeling Cantonment so impressed his superiors in Calcutta Headquarters that he was instead asked to proceed to Karnal in Haryana and work on re-location of that cantonment to a new place. Hence, in late 1842, Captain Robert Napier arrived in Karnal with a wife and child in tow.

“The duties which awaited him included the choice of the site for a new cantonment, as it had been decided to abandon Kurnaul on account of the mortality among the troops there, and the urgency was due to the return of troops from service in Afghanistan,” the memoirs say.

Napier chose the land where the present Ambala Cantonment is today located and chose a new system of laying out buildings and barracks which provided ventilation and sanitation to prevent a repeat of the conditions at Karnal.

In 1844 he was occupied in laying out the hill stations of Subathu and Kasauli, on the route to Shimla in Himachal Pradesh. In his letters to his wife, Napier reveals how the name Kasauli was chosen for the new cantonment in preference to that of Dagshai.

“I went this morning with the Governor-General to the suspension bridge on his way to Simla. He was so gracious and affable in all public matters, that I could not possibly intrude any private ones of my own. I believe I shall have the general direction of the new station. He has asked me to give him my ideas on the plans for forming it, and everything is to be on a liberal scale. The name of the place to be Kooshiula from the river near it [now called River Kaushalya], Dugshai being not euphonious (!!)…” he wrote to his wife from Subathu.

It is clear that in due course Kooshiula changed to the more pronounceable Kussowlie and then to the present day Kasauli.