As two groups flocked to two parades on July 8, one pro-India and the other anti-, a gurdwara in Canada’s Oakville, 40 km from the Greater Toronto Area neighbourhood of Brampton, was seeing a gathering of another kind. A congregation of Sikhs and Hindus had come together to pray for peace with the recital of the ‘Sukhmani Sahib’.

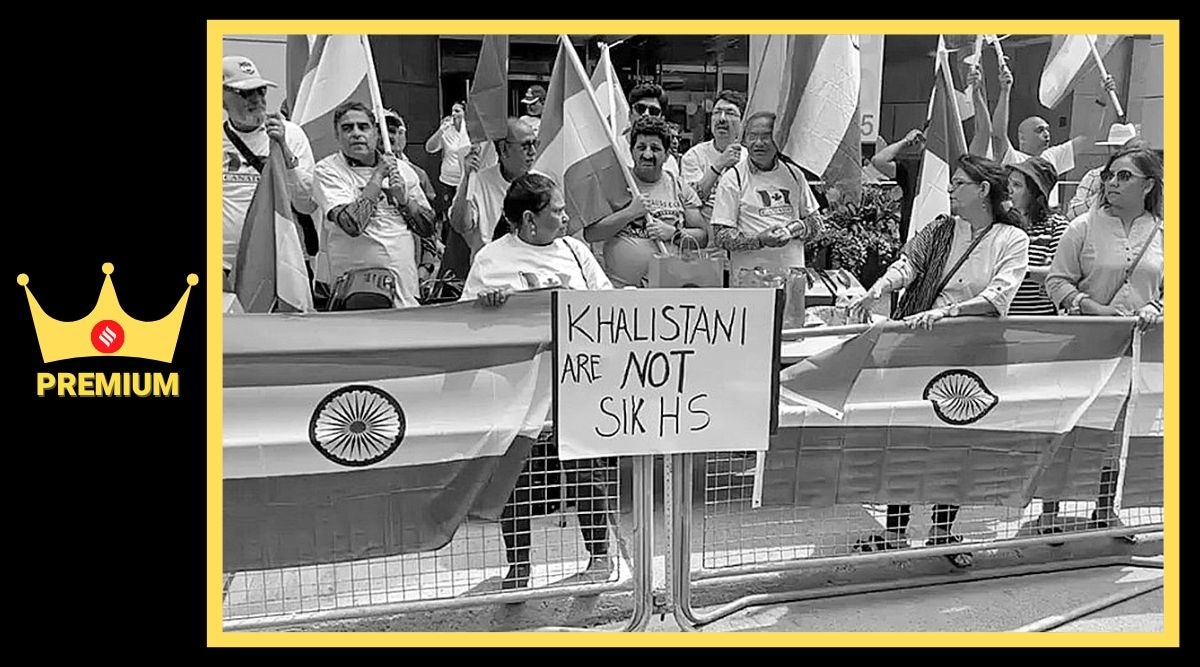

Since November last year, the din caused by pro-Khalistan voices in Canada, amplified by social media, have drowned out such pacifist voices. Yet, members of the Indian diaspora and other prominent voices in Canada say the recent incidents – including three so-called referendums on Khalistan organised by the outlawed Sikhs For Justice and a float at a parade on July 4 that re-enacted the assassination of former PM Indira Gandhi, inviting the strictest condemnation from the Indian government – should be seen for what they are: noise.

Earlier this year, India had lodged a protest with Canada, flagging actions of “separatist and extremist elements” against Indian diplomatic missions and consulates.

“It has turned ugly,” agrees Inderjit Singh Bal, former president of the World Sikh Organisation (WSO), “but the noise does not represent the silent majority of the Sikhs here. As they say in Punjabi, jaddon dhol bajda hai te been di awaaz nahin sundi (when someone is beating the drum, no one can hear the sound of the wind instrument).”

Despite an attempt by pro-Khalistan voices to stage a comeback, many point out that they represent little more than the fringe. Back home in Punjab, too, the Khalistan agenda has found little resonance. This was proved in the 2021 Punjab Assembly elections, in which separatist proxies managed only 2.5 per cent of the vote share in the state. More recently, the arrest of self-styled preacher and Khalistan protagonist Amritpal Singh at Moga in April evoked a bigger reaction abroad than at home.

Gurpreet Singh, a broadcaster and talk show host at Spice Radio in Canada, says, “The ground reality is that not all Sikhs support Khalistan; it’s mostly all hype… Remember, Khalistan had no popular support in Punjab, even at the height of militancy, when the state saw police excesses.”

Terry Milewski, a veteran CBC News journalist who authored Blood for Blood: Fifty Years of the Global Khalistan Project in 2021, says it’s important to remember that “you cannot use the word Sikhs and Khalistanis interchangeably, for an overwhelming majority of 98 per cent of Sikhs do not support this agenda”.

Story continues below this ad

A ‘fringe’ seeking relevance

The demand for Khalistan is not alien to Canada. Old-timers recall how Surjan Singh Gill, a mild-mannered man born in Singapore and raised in India and England, first set up the office of the ‘Khalistan government-in-exile’ in Vancouver on January 26, 1982. Though he also printed blue Khalistani passports and colourful currency, he gained little fandom among the local Sikhs. Some of his activists carrying posters in support of Khalistan were beaten up during the Vaisakhi procession that April. They were allowed to join in only after they had thrown away their placards.

But 1984 changed it all. Operation Bluestar, launched by the Indian Army to flush out militants from the Golden Temple, and the anti-Sikh riots that followed the assassination of Prime Minister Indira Gandhi gave this movement an unprecedented fillip among the diaspora.

Darshan Singh Tatla, an acclaimed academic who chronicled the diaspora, famously wrote that these two incidents had turned a proud and self-confident community into a “wounded, vulnerable minority”. As Tatla put it, “The quest for a homeland became part of the Sikh diaspora’s identity.”

Screengrab of the video showing a parade in Brampton purportedly celebrating the assassination of Indira Gandhi. (Twitter)

Screengrab of the video showing a parade in Brampton purportedly celebrating the assassination of Indira Gandhi. (Twitter)

The aftermath saw the formation of a number of outfits with secessionist ideologies, among them the International Sikh Youth Federation (ISYF) and the Babbar Khalsa in Britain. The ISYF, banned in Canada in 2003, has openly called for an independent Sikh state free from “Hindu imperialism”, while the Babbars orchestrated the June 1985 Air India bombing.

Story continues below this ad

A leader of the WSO, which was set up in July 1984 to represent Sikh interests on the world stage, said there are three kinds of Khalistani activists in the West, including Canada. “The first category is of those directly aggrieved by police excesses in Punjab in the 1980s; the second is of people who have made a business out of it, and the third are those propped up by agencies inimical to India.”

Ujjal Dosanjh, the first person of colour to become premier of British Columbia in February 2000, defines another category: a ‘fringe’ seeking relevance and attention. “Many of them are not well integrated into society, they are not highly educated, they cling to grievances, real or imagined, and take pride in fighting for this mythical homeland,” he says.

Dosanjh, who has always been very open in his criticism of the Khalistanis, narrowly escaped a murderous attack in 1985. He says the Khalistan issue is “overblown” and shouldn’t be a sticking point in a “mature relationship” between India and Canada.

Dave Singh Hayer, former MLA of Canada’s Surrey Tynehead and president of the Association of Former MLAs of British Columbia, says, “Most of these individuals are motivated by business interests since they receive substantial funding, not only from local sources, but also from foreign countries like China and others.”

Story continues below this ad

Among such protagonists is Ranjit Singh Khalsa, former ISYF president, who came to Canada as a refugee in 1988. He is now associated with Banda Singh Bahadur Gurdwara in Abbotsford, British Columbia, where he advocates for Khalistan. Khalsa’s plea for citizenship was denied by a Canadian federal court in 2021. A judicial review of the decision by a member of the Immigration and Refugee Board found Khalsa to be inadmissible to Canada for having been an alleged member of the ISYF.

Khalsa claimed that the concept of Khalistan was thrust upon the Sikhs due to the “actions” of the Indian government.

‘Tacit patronage of Canadian politicians’

The Khalistan movement in Canada hasn’t followed a linear path, rising and ebbing through the years, often reflecting the changing politics of India and its subcontinent. Gurpreet Singh, the talk show host, says that at one point, soon after the Atal Bihari Vajpayee government came to power, they thought it was in the past. Bhishma Agnihotri, then Ambassador-at-large, met some prominent Khalistanis and it appeared that reconciliation had begun. “But of late people ask if there can be a demand for a Hindu rashtra, how can you prevent call for Khalistan.”

Amardeep Singh, the counsel for passport, visa and community affairs in Vancouver in 2014, says the Modi government too has made attempts at reconciliation. “At least 400 people in my jurisdiction in western Canada were taken off the blacklist. I met so many radicals and there were hardly any protests outside the (Indian) Consulate those days. We celebrated the 350th birth anniversary of Guru Gobind Singh and the 550th anniversary of Guru Nanak across the globe, with the Indian government spending millions of dollars in just one year.”

Story continues below this ad

The recent pro-Khalistan incidents began with the ‘referendums’ last November. Though most Canadian Sikhs agree that these are pure gimmickry, videos of people waving the “Khalistan flag” and SFJ chief Gurpatwant Singh Pannun leading the sloganeering went viral on social media and ignited a war of words in the virtual world between self-styled Sikh and Hindu nationalists.

Surinder Sharma, past president of the 1,000-strong IIT alumni association of Indians in Canada, blames the recent resurgence and the increasingly vicious virtual propaganda on Pakistan. “They want to weaken Indians in Canada by driving a wedge between them.”

Former premier Dosanjh attributed the uptick in pro-Khalistan voices to the tacit patronage of Canadian politicians of Indian descent. In a recent interview, he said they had “infiltrated” local politics.

In 2012, Jonathan Kay, managing editor for comment at the National Post, pointed out how Vancouver Sun’s Kim Bolan reported about a militant minority of Sikhs “vitiating” British Columbia Vaisakhi parades by displaying images of Kanishka bomber Talwinder Singh Parmar, Indira Gandhi’s assassin Satwant Singh Bhaker and the killers of General AK Vaidya. “In many cases, naïve Canadian politicians, unable to read the Punjabi descriptions, have stood idly by, clapping their hands as images of these ‘martyrs’ rolled past,” wrote Kay.

Story continues below this ad

Kanwar Sandhu, a former MLA and veteran journalist who has covered the militancy in Punjab, rued that a certain section took unfair advantage of the liberal and democratic policies, and human rights charter of the Canadian government. Others, like Milewski, the veteran CBC News journalist, openly blamed vote-bank politics. Though comprising just 2 per cent of Canada’s population, Sikhs are concentrated in pockets and have a large number of lawmakers. The 2021 elections saw 17 Liberal MPs of Indian origin.

Milewski says the Khalistan protagonists, a tiny minority within the diaspora, try to keep their political influence both with the Left and Right. Which is why politicians look the other way when they spew their extremist agenda, he says.

Gurpreet Singh, whose wife Rachna Singh is a New Democratic Party (NDP) MLA and the Minister of Education and Child Care, lamented that the biggest fallout of the resurgence was the polarisation of Canadian Indians. “Now people identify themselves as Hindus and Sikhs,” he says.

Another worry, though not a recent phenomenon, is the increasing influence of radicals on gurdwaras. In December 2018, 14 gurdwara management committees of Ontario met at Jot Parkash Gurdwara in Brampton and used a local law against trespassing to impose a ban on the entry of Indian government representatives in gurdwaras under their control. The Gurdwara Sahib Dasmesh Darbar in Surrey has long been associated with hardliners, and openly displays huge posters of Parmar and other “martyrs”. The Guru Nanak Sikh Gurdwara in Surrey, once with moderates who often hoisted the Indian flag, was also taken over by radicals led by Hardeep Singh Nijjar, who once hosted Pakistani Consul General Janbaz Khan at the gurdwara. Nijjar was shot dead on the premises of the gurdwara in June this year.

Story continues below this ad

Maninder Gill, the president of Friends of Canada & India Foundation, which takes up Indo-Canadian issues, says the “attempt to influence” youngsters, both in person and in the virtual world, is “most disturbing”. “Khalistani groups are luring new students from India with ‘welcome packages’, which include financial support for their education and weekly groceries. In return, they are expected to participate in protests,” he says.

There is also an attempt to peddle an anti-India narrative through guest speakers at certain schools, he said, adding that the new generation is particularly vulnerable to propaganda as they have no memories or ties with India, other than mostly through their grandparents.

Gill says, “The fact is that there are certain unresolved issues, such as justice for the victims of the anti-Sikh pogrom of 1984 and the continued detention of Sikh prisoners who have served their jail terms, which give rise to allegations of Sikhs being victimised.”

Community members, both pro and against the idea of Khalistan, agree that certain issues arising from the reorganisation of Punjab in 1966, including the division of river waters and the shared capital of Chandigarh, continue to fester and require closure.

Story continues below this ad

Kanwar Sandhu says it is a very complex issue that needs deft handling. “On the one hand, there are long-pending grievances from 1947 that need to be addressed. The people behind the movement seem very confused; it is just going on and on with no thought. What are the geographical boundaries of a separate state they seek? Is it physical or emotional? Is it in the interest of the Sikhs at all? Will they ever want to return? There are no clear answers. The movement only tends to alienate the protagonists from the mainstream,” he says.

The common Indo-Canadian Punjabi, emotionally bullied by separatists who often equate Khalistan with the reverence reserved for the Sikh faith, chooses to remain silent. But of late, some have begun to wonder if the actions of a few will fritter away the hard-won privileges of the early Punjabi settlers, who landed on Canadian shores in 1897, and battled racism and hostile weather to get equal rights and a home they could proudly call their own.

Harji Bajwa, who migrated to Canada at the age of 16 in 1972 and recently set up the Hindu Sikh Unity Forum, voiced the sentiments of many when he says, “I can’t understand why people who have chosen to migrate here to build a new life are now fighting for a homeland to which they will never return.”

(With inputs from Anju Agnihotri Chaba)

Screengrab of the video showing a parade in Brampton purportedly celebrating the assassination of Indira Gandhi. (Twitter)

Screengrab of the video showing a parade in Brampton purportedly celebrating the assassination of Indira Gandhi. (Twitter)