‘Khalistan has no future, is championed by those who are fighting irrelevance’: Dosanjh

It's the responsibility of high commissions abroad to paint a balanced picture of India, former politician and author Ujjal Dosanjh says.

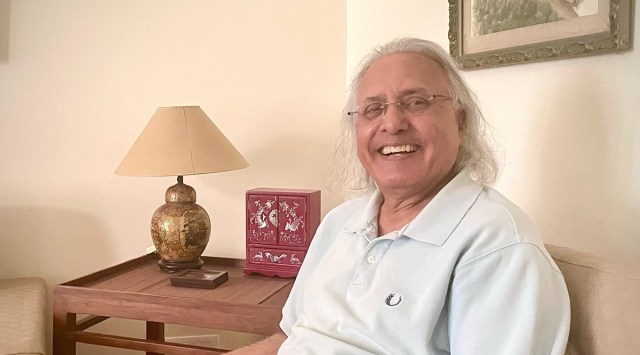

Ujjal Dosanjh, the first Sikh and person of colour to become the premier of British Columbia. (Express)

Ujjal Dosanjh, the first Sikh and person of colour to become the premier of British Columbia. (Express) “Khalistan has no future, it never had, as people living in Punjab don’t want it. For most of those who champion it, it’s just a way of staying relevant and collecting funds.” Ujjal Dosanjh, the first Sikh and person of colour to become the premier of British Columbia, makes no secret of his scorn for separatists. Commenting on Gurpatwant Pannu, the man behind the banned outfit Sikhs for Justice and Khalistan referendums, he says, “The Pannus of the world are irrelevant to the societies they live in, so they seek relevance in some cause.”

Dosanjh, 76, who has retired from active politics to become a full-time author, was in the city to launch his refreshed memoir, “Journey After Midnight: India, Canada and the Road Beyond,” and novel “The Past is Never Dead”. The latter is the story of a 16-year-old Dalit boy, who continues to be dogged by caste violence even after he moves to Britain with his father.

The clamour for Khalistan by a tiny fringe living abroad, he says, is not new. “It was in 1971 that Jagjit Singh Chohan, who would peddle his divisive agenda in Canadian gurudwaras, made the declaration of Khalistan in a one-page advertisement in one of the leading national dailies of the US,” says Dosanjh.

Starting as a 20-year-old sawmill worker when he set foot in Canada in the 1960s, Dosanjh remained steadfast in his opposition to Khalistan as he laid the foundation of Canadian Farmworkers Union, many of whose members are Punjabi immigrants, graduated as a lawyer and became the first Sikh attorney general of British Columbia. A violent attack in 1985 left him with 80 stitches on his head and a hand broken into several pieces but he was undaunted.

He’s seen the movement ebb and flow during the last five decades.

The Bhindranwale phenomenon followed by Operation Bluestar, he says, allowed Khalistanis, who were a minuscule fringe in the diaspora, to claim the centrestage. “Some of them were my clients, and they didn’t speak much English. They were not well integrated into society, they wanted to belong, and were easy targets for people like Chohan, who gave them a bigger cause,’’ says Dosanjh. “The Khalistan movement comes out of the sense of irrelevance that some people feel,” he reiterates.

The movement has also muddied the Canadian politics. “Unfortunately, some separatists, although not violent, have become part of the mainstream political parties in Canada. The government on its part says we believe in democracy and free expression, so we can’t prosecute people unless they indulge in violence.”

Support for Khalistan, he says, also stems from the narrative that Sikhs have no freedom or equality in India and are being butchered. “Some people latch on to one stray incident and paint a permanent picture of repression and injustice. Action against Amritpal (the chief of Waris Punjab De outfit) was a minor issue in India but it was amplified in Canada and there were demonstrations in his support although they were largely harmless.’’

Dosanjh says it’s the responsibility of high commissions abroad to paint a balanced picture of India. “The government of India expects immigrants to defend India. I love India very much. I have been defending India all my life. But people like me are being enfeebled by the Hindu rashtra narrative and right-wingers with their vitriol against Muslims. People turn around and tell me your India doesn’t exist anymore. Meanwhile, officials at the high commissions behave like lords and do nothing.’’

On Khalistan becoming the stumbling block in the relations between Canada and India, Dosanjh says, “There is a sort of whiplash reaction by the government of India to the demand for Khalistan. Under Vajpayee and PM Narendra Modi, the Indian government has given visas to former terrorists because they wanted to welcome them back into the mainstream. But when someone there shouts slogans in favour of Khalistan, they react. The GOI should move on, they should not be so worried. Many people who were angry in the 1980s have turned away from Khalistan. By and large, most people who support it are lost souls.’’

Dosanjh, meanwhile, continues to face the backlash. Recently during the Sikh heritage month celebrations, the BC legislature tweeted the names of all the Sikh parliamentarians but left him out. “When a woman pasted a photo of my young self when I used to wear a turban, some people reacted by saying, ‘He is not a Sikh’.” On his Wikipedia page, where he wrote his full name as Ujjal Dev Singh Dosanjh, someone edited out the ‘Singh’.

But Dosanjh, the author, remains unfazed. He’s already penned four novels of which one is titled “Godse’s Children”, the other “Gandhi’s Bastards”. The third is on extremism in Canada. “It starts from the point when a police officer was gunned down at Golden Temple in the 1980s,” he says. His preoccupation with the past, he says, is best explained in a line from William Faulkner: “As the past is never dead, it is never the past.”