Why this is already one of Karnataka’s worst summers yet

Dry taps to distress sales, woes mount for drought-hit Karnataka: Water supply once every 15-20 days, anger over inadequate relief

A queue at Gangimadi Nagar in Karnataka’s Gadag, where residents say water is supplied only once a month. (Express photo: Akram M)

A queue at Gangimadi Nagar in Karnataka’s Gadag, where residents say water is supplied only once a month. (Express photo: Akram M)Waiting seven to eight days for water supply during summer months is not unusual for Siddesh Angadi, 52, a shopkeeper. This year however, the resident of Karnataka’s Gadag seems worried.

“Water supply is generally bad during the summer, but we always get water every seven to eight days. The situation seems grim this year due to the drought. While many houses have some form of storage, it is a major headache in areas where people are not well off,” says Angadi.

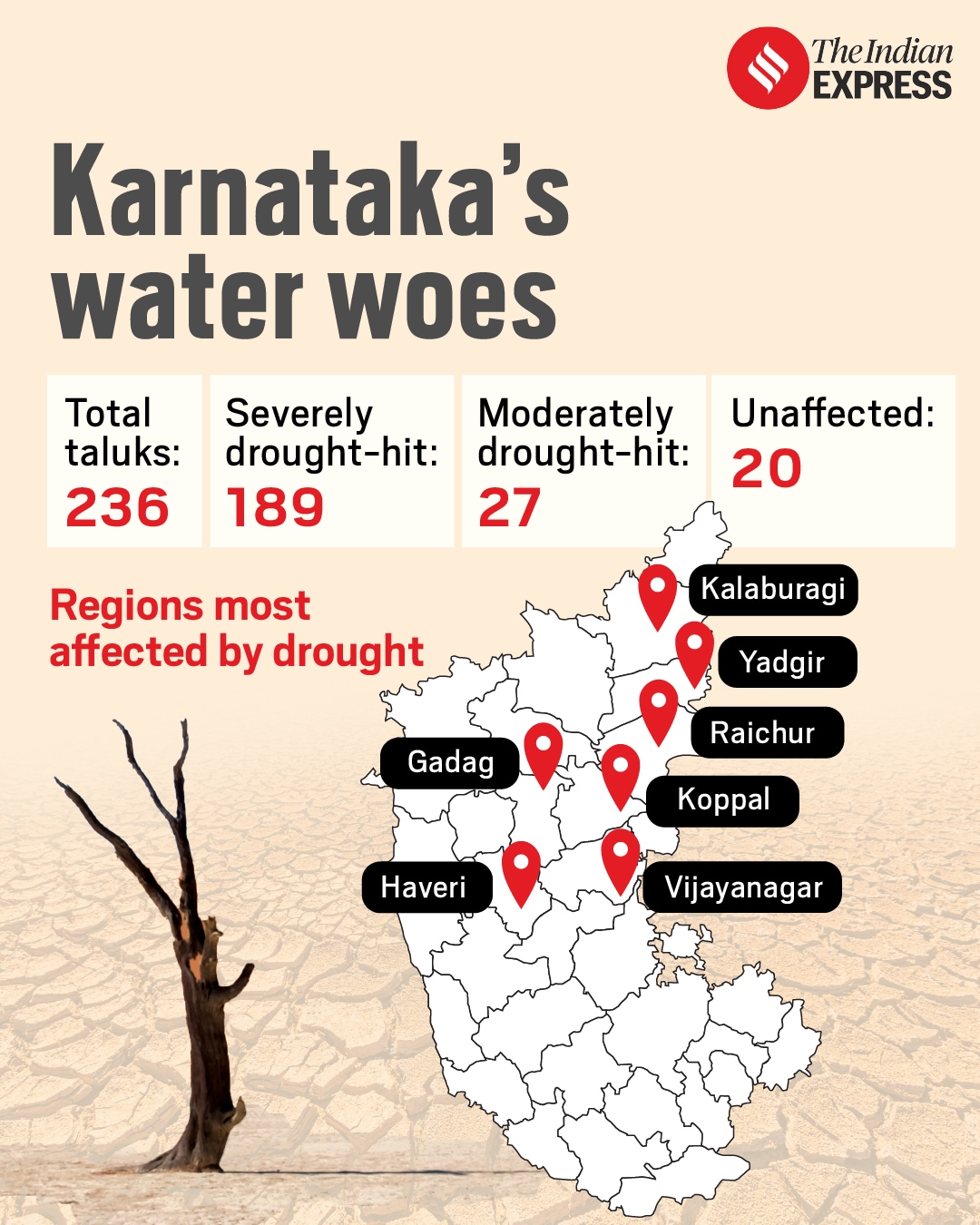

Karnataka is facing one of its worst droughts in recent years. While Bengaluru’s water shortage in has attracted national attention, the situation in other parts, especially north Karnataka, is particularly acute. A failed monsoon, dotted by sporadic spells of heavy rain last year, has resulted in a major crisis, especially in the arid regions of north Karnataka.

In cities like Haveri and Gadag where water sources begin to dry up from March, residents say they are being forced to wait for 15 days — 30 in some cases — for local bodies’ water supply. Gadag Deputy Commissioner M L Vyshali told The Indian Express that it was very difficult to manage water supply for the city and nearby villages in Gadag district during the summer months.

Karnataka’s water woes

Karnataka’s water woes

Haveri City Municipal Council Commissioner Parashuram Chalavadi said the city was dependent on borewells for water supply that due to water scarcity in rivers. “We are recharging borewells by filling tanks in and around the city,” he said. From Heggere Kere — a large water body near the city — water is being dumped to smaller tanks so that borewells can be recharged. “Many departments are working together to dump water from the lake to these tanks,” he said.

People queue up for potable water at a ‘water ATM’ at Rajarajeshwarinagar. (Express photo by Jithendra M)

People queue up for potable water at a ‘water ATM’ at Rajarajeshwarinagar. (Express photo by Jithendra M)

From utensils to buckets, every container at the homes of people in the affected regions have been deployed to store water till the supply is replenished. The situation has left them further anxious about the peak summer months of April and May.

Areas near the dam suffering badly

While all districts in north Karnataka are suffering, the situation is worse for regions dependent on the Tungabhadra dam. The water level in the dam in the first week of March last year was 24.56 thousand million cubic (TMC) feet. The dam has just about 1.7 TMC of water at present.

Water levels in dams

Water levels in dams

Local administrations of districts dependent on the dam, including Haveri, Gadag and Koppal, are preparing for a major crisis in summer months.

Data from the Karnataka State Natural Disaster Monitoring Centre (KSNDMC) showed a deficit of over 60 per cent in rainfall between July 30 and August 26. Seasonal data shows odd spells of heavy rain in the later parts of the monsoon, reducing the deficit to 25 per cent at the end of monsoon. However, in the Malnad region — the key catchment area for Cauvery and Tungabhadra rivers — rainfall shortage was 40 per cent.

The situation led to Agriculture Minister N Chaluvaraya Swamy remarking recently that agriculture was set to fall by over 50 per cent.

Karnataka had set a target for cultivation in 82.35 lakh hectare in the 2023 kharif season. However, drought conditions resulted in crop losses in 42 lakh hectare land. For farmers in the state, the drought situation has proved to be a double whammy — reeling from crop failure and now water has become scarce. They are still awaiting compensation from the Centre under the National Disaster Response Fund (NDRF). As far as relief is concerned, the state government released Rs 628 crore — Rs 2,000 per person — as interim compensation for 33 lakh farmers in the state in January. Besides this, the farmers received two instalments of Rs 2,000 under the PM-KISAN scheme over the past eight months.

Karnataka had in its memorandum to the Centre last year sought a compensation of Rs 18,172 crore, including Rs 4,663 crore under NDRF guidelines. There is also palpable anger among farmers over the PM Fasal Bima Yojana, with many opting out of the scheme due to inadequate compensation. On March 6, Haveri farmers had blocked major roads in protest over the delay in claim settlements.

Several houses use containers to store water as depleting water levels in the Tungabhadra reservoir has forced local bodies to ration water supply. (Express Photo by Akram M)

Several houses use containers to store water as depleting water levels in the Tungabhadra reservoir has forced local bodies to ration water supply. (Express Photo by Akram M)

An official in Kalaburagi district said, “The delay in releasing claims under PM Fasal Bima is due to the queue system. Those who apply for compensation first, get it first under the scheme.”

S B Jogannavar, secretary of Karnataka Rait Sena, a North Karnataka farmers’ body, said almost half the farmers failed to get compensation. “If a farmer dies, their family cannot claim compensation for crop loss even if they paid the premium,” he claimed.

Prakash Byadagi, a farmer from Kodihalli in Haveri district, said while the expense to grow cotton was around Rs 18,000-20,000 per acre, the compensation received was just Rs 2,500 to Rs 3,000 per acre. “We should at least get Rs 14,000 per acre”.

Though Subash Girannavar, a farmer from Nargund in Gadag district, is among the few who received the compensation, he said it was “not enough”. He said, “In 2018, I received a compensation of Rs 1 lakh for the crop cultivated on 20 acres. This year, I received just 22,000.”

In 2021, the Centre had permitted Karnataka to increase the number of work days under the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MNREGA) from 100 to 150 days due to drought conditions that year. This year, it is yet to permit a similar demand made by the state soon after drought was declared in the state.

“Potentially problematic villages” identified

As the crisis mounted, the Karnataka government has identified 7,408 villages as “potentially problematic villages” in terms of water supply. After a recent meeting, the Chief Minister’s Office had said that agreements were made with 7,340 private borewell owners for water supply. These villages are besides the 675 villages that are already facing problems.

The drought has also led to distress sale of cattle across the state. Lack of adequate fodder has forced the hands of small farmers, who are finding it hard to take care of their cattle. Farmers who brought a pair of oxen for around Rs 1.2 lakh are reportedly selling it for half the price.

“Crops have failed and money is scarce. There is not enough fodder also. We did not have any alternative,” said Yellappa Muthlokotu, a farmer from Asundi in Gadag district, who sold his two oxen at a cattle fair held at Gadag recently.

Farmers are also unhappy over the state’s failure to stop those residing near rivers and reservoirs from pumping water directly into their fields despite the crisis. “While those farmers are harvesting their crop, we are struggling to even get water,” said Rudrappa, a farmer from Betageri.

Gadag Deputy Commissioner Vyshali said the problem had aggravated due to some farmers with lands close to barrages and dams. “They draw water at night to water the crops. This is a major problem for us,” she said.

In places like Kalaburagi, where tur dal is the main crop, dal mills have not been spared either. Wide fluctuations in prices, attributed largely to apprehensions of failed crops, have forced many small mills to shut shop — at least for the current season.

“Only those with means to procure dal despite the fluctuating prices have been able to keep the mills open,” said Shanaranabasappa Heggani, a mill owner in Kalaburagi’s Kapnoor Industrial Area.