Norway’s Crown LNG, which plans to build a 7.2-mtpa (million tonnes per annum) offshore liquefied natural gas (LNG) regasification terminal in Andhra Pradesh’s Kakinada, believes that gravity-based structures (GBS) are the answer to conventional offshore LNG terminals—floating storage regasification units (FSRUs)—in harsh weather conditions. Kakinada terminal will be India’s first, and possibly the world’s second, GBS LNG terminal, offering round-the-year operations—something FSRUs cannot offer in rough waters. The final investment decision (FID) of the $1-billion project is expected in 2025 and the facility is likely to be commissioned in 2028, according to Crown LNG’s Chief Executive Officer SWAPAN KATARIA.

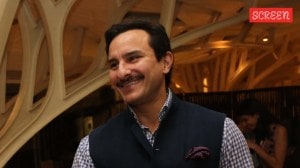

In a freewheeling interaction with SUKALP SHARMA, Kataria provides insights into the GBS technology, purported advantages over conventional LNG terminals, and updates on the Kakinada project’s progress. Edited excerpts:

What exactly is a GBS?

It is essentially a concrete structure with a ballast section at the bottom with empty concrete blocks. The section acts as a balloon when empty, helping the structure float. At the location where you want to base it, you fill it up with gravel, making the structure heavy enough to sink and sit on the seabed. So, it is not bolted or held by cables. Gravity is holding it. It is engineered in a way that it sits there for 40-50 years without budging even an inch. The LNG terminal is built over that GBS.

GBSs have been utilised mostly for upstream oil projects. So far, only one has been built for LNG—Adriatic LNG—in Italy. And the only liquefaction facility (which converts gas to LNG) would be Russia’s Arctic LNG 2.

Apart from round-the-year operations, what are the advantages of GBS units vis-à-vis FSRUs and land terminals?

There are quite a few. GBS LNG units offer a safer working environment because sea wave volatility does not affect its structural stability. The other advantage is no extra pressure on ports. It has an offshore landfall point and the pipeline to land is from under the seabed. So, it doesn’t need a large footprint on land. A GBS unit can be hauled to another offshore location and handed over to another operator. So, the economic life of the asset is much longer and it can be evacuated to a new market if, for any reason, it cannot continue to operate at the initial location. For international financiers, that is an attractive proposition.

Despite advantages, why have GBS LNG units not taken off in a big way?

I think it is a mix of multiple factors. LNG is relatively a new market that has picked up in the last two decades. It’s not something that has grown over the last 100 years, like oil. The Koreans were really fast in developing FSRUs. Most people took the path of least resistance and ended up following that model (FSRUs) or set up land-based terminals. Everybody went after benign waters or areas where breakwater could be easily built for an FSRU. But those vanilla locations are now gone and developers have to contend with harsh weather conditions.

In terms of project costs, how does a GBS regasification unit compare with other types of LNG terminals?

If a land-based terminal costs $120, a GBS unit would cost $100, and an FSRU’s core cost would be $70-80. For an FSRU, there will be additional costs like breakwater. All costs, including those needed to make conditions benign for FSRUs, would be much higher. For land-based terminals, dredging may be required from time to time—an additional ongoing cost. GBS units don’t have these overheads.

Story continues below this ad

Earlier you had planned to close the FID by 2022-end, but it has been delayed. What is the current status and estimated timeline?

It has been a moving target as approvals took more-than-expected time. We are completing the remaining part of the engineering, with which we will finalise the design and the EPC (engineering, procurement, construction) contract. That will be followed by final negotiations with potential users. All this will take 15-18 months and we are hoping to get this (FID) done by mid-2025. The construction would then start. It is a 30-month construction, with another three-six months for commissioning. So, 2028 is what we are targetting for project completion.

Which companies have shown interest in using the terminal? At what stage are the negotiations?

I cannot name any potential customer at this stage, just that they include India’s oil and gas majors and we would have a mix of government and private companies. Talks with government companies could take longer as there may be some approvals required.

We are obligated to maintain 15% capacity for spot and short-term cargoes, which means we can offer about 6.1 mtpa. We plan to place about 3.5-4 mtpa on 20-year contracts, and the rest on 10-year contracts.

We are only giving regasification as a service, and not buying the molecule (LNG) and then selling it. It’s easier for a financier to look at us favourably because in the absence of the molecule risk, it becomes an infrastructure and technology business that is not really impacted by commodity price fluctuations.

Story continues below this ad

Are you open to Indian oil and gas companies acquiring stake in the project? Have there been any discussions?

Yes, we have been in discussions with them. We have received interest from some of them for investments in the project, apart from terminal usage. We would prefer a strategic investor, someone who is in the gas business, or has experience in operating LNG terminals, and our customers. Why would we not accept an investment from a company that is already working with us and has far more experience in operating in India?

How safe would a GBS be in harsh weather conditions of India’s east coast? What about calamities like earthquakes and tsunamis?

Our initial part of engineering was to look at the patterns of the typhoons, hurricane season, wave heights, and the winds in that area. Our engineering department looked at the 100-year history and even beyond, whatever data was available. We have designed it keeping in mind all these parameters based on historical data, providing more than enough margins. For instance, if data suggests that the maximum wave heights in the area have been 6 metres, we would go for a construction height three times that above the water level at high tide. As for earthquakes and tsunamis, the design can handle those to a large extent. Of course, like for any project, a calamity of unprecedented intensity and scale is a risk.

Is Crown eying other geographies in India and overseas for GBS projects?

We have another project in the works in Scotland, which was earlier planned as a GBS but now we have changed plans to an FSRU as Scotland wants it to be built at the earliest. For GBS units, we are looking at Bangladesh, Vietnam, and Atlantic Canada. We have also received enquiries from Pakistan. But we are focusing on our projects in India before getting involved anywhere else. Our plan would be to utilise the Kakinada project to build more such units in India and globally.

Beyond LNG, what are the other infrastructure facilities that you can offer using a GBS?

We have four generations of models on the GBS. The first as a natural gas liquefaction facility, second as an LNG regasification facility, third as an integrated power plant, and fourth as a green hydrogen to green ammonia unit. All of these would be feasible and viable. But we are focussed on getting the Kakinada project off the ground before diving into anything else.