Aishwarya Khosla is a journalist currently serving as Deputy Copy Editor at The Indian Express. Her writings examine the interplay of culture, identity, and politics. She began her career at the Hindustan Times, where she covered books, theatre, culture, and the Punjabi diaspora. Her editorial expertise spans the Jammu and Kashmir, Himachal Pradesh, Chandigarh, Punjab and Online desks. She was the recipient of the The Nehru Fellowship in Politics and Elections, where she studied political campaigns, policy research, political strategy and communications for a year. She pens The Indian Express newsletter, Meanwhile, Back Home. Write to her at aishwaryakhosla.ak@gmail.com or aishwarya.khosla@indianexpress.com. You can follow her on Instagram: @ink_and_ideology, and X: @KhoslaAishwarya. ... Read More

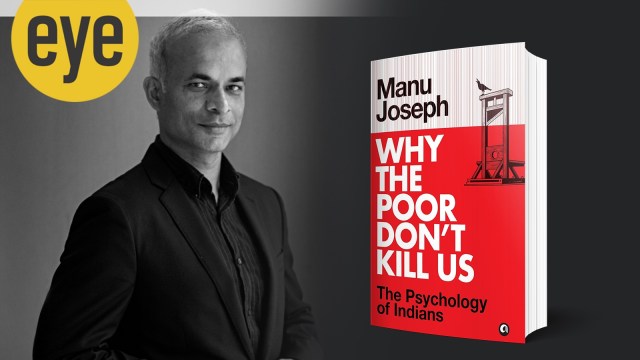

Why the Poor Don’t Kill Us – Manu Joseph’s darkly witty autopsy of India’s uneasy peace amid inequality

In this sharp and unsettling collection, Joseph asks why inequality endures, and finds the answer in habit, hypocrisy and hope.

Manu Joseph’s Why the Poor Don’t Kill Us is a biting, darkly sardonic meditation on India’s calm amid crushing inequality. (myriadeditions.com, amazon.in)

Manu Joseph’s Why the Poor Don’t Kill Us is a biting, darkly sardonic meditation on India’s calm amid crushing inequality. (myriadeditions.com, amazon.in)Manu Joseph’s Why the Poor Don’t Kill Us is a sardonic exploration of one of modern India’s most jarring juxtapositions: the calm coexistence of obscene wealth and abject poverty.

Why, Joseph asks, do the poor not rise against the rich? Why do they not burn the palaces and banks? Why do they not claw their way out of their misery to destroy those who live behind high walls and tinted car windows?

The questions are grotesque and unsettling, yet once asked, are impossible to ignore, and in Joseph’s hands provide a peek into the collective Indian psyche.

Joseph begins with scenes of devastation from the 2001 Bhuj earthquake, where human suffering lays bare the pragmatism of the poor. These early vignettes – a man calmly directing traffic while his family lies trapped under rubble or others hounding photojournalists for proof of death – set the tone of the book.

The poor, he writes, accept tragedy as routine, as though misfortune were a law of nature. This is a portrait of people so exhausted by survival that they cannot imagine resistance.

For Joseph, the Indian poor embody a paradox. They see the extravagance of the wealthy every day, yet rarely rebel. “They could,” he writes, “crawl out from their catastrophes and finish us off.” The fact that they do not is the question that sustains the book.

The result is an acerbic social anatomy of a nation that prides itself on democracy while tolerating medieval inequality. The poor, he argues, are “ancient people living in modern times,” trapped in a fatalistic loop that treats suffering as destiny.

Across eighteen essays, he dissects how inequality persists because the poor have been culturally, morally, and psychologically conditioned to accept their fate.

False consciousness and the comfort of ugliness

A Marxist reading of Joseph’s argument is unavoidable. He treats the poor as people trapped within a system that has colonised their imaginations. In classical Marxist terms, they suffer from false consciousness, a condition in which the oppressed internalise the morality of their oppressors.

Religion, caste and nationalism combine to transform injustice into destiny. Even ugliness, Joseph observes, can be political. India’s civic ugliness, he argues, “reassures the poor that the nation has not left them behind.”

It is an extraordinary insight. Where European cities mask inequality beneath order and cleanliness, India displays its disorder as proof of belonging. The broken pavements and peeling walls tell the poor that this chaos is theirs too. Ugliness, in Joseph’s view, functions as a sedative. It maintains the illusion of equality by ensuring that no one feels excluded from the national decay.

India’s stark coexistence of luxury and deprivation that fuels Joseph’s piercing questions. (Express photo by Oinam Anand. )

India’s stark coexistence of luxury and deprivation that fuels Joseph’s piercing questions. (Express photo by Oinam Anand. )

The poor against the poor

Joseph observes that the poor, like the rich, reserve their deepest resentment for their equals. “The poor are the worst enemies of the poor,” he writes. It describes a society so divided by caste, gender and micro-hierarchy that class solidarity is impossible.

Envy is lateral rather than vertical. A poor man competes not with his employer but with his neighbour. In this sense, Joseph’s India is one in which the revolutionary subject (Marx’s proletariat) has been dismantled by a thousand tiny divisions.

The moral theatre of the middle class

No less merciless is Joseph’s portrayal of the urban middle class, whom he calls “the new conscientious sahibs.” They are polite to their servants, and sometimes publicly remorseful, yet their civility functions as a mask. They rely on the poor while disavowing the exploitation that sustains them. In Marxist terms, they are the petit bourgeoisie, the moral camouflage of capitalism.

Joseph writes with wicked precision about this hypocrisy. “The new conscientious sahib,” he writes, “even exclaims on social media how cruel it is that maids are ‘expected to be invisible’.… is unlikely to … let the maid use the toilet, or the cutlery.” Such lines sting because they are neither exaggerated nor false. They describe a class that believes it can purchase moral safety with manners.

One of the more fascinating essays, ‘The Defeat Of The Amateur Indian, And His World Framed In English’, extends Joseph’s critique into culture. He explores what happens when Indians stop thinking in their mother tongues and begin thinking in English. For Joseph, this shift produces a new kind of alienation. The English-speaking elite are estranged from their own country, yet still rule it. They adopt Western ideals of secularism, liberty, and human rights without the social conditions that produced them. They are, in his phrase, “amateurs” in their own nation. Joseph’s portrait of their unease, their constant self-consciousness, is both cruel and accurate. It is also, in moments, surprisingly tender. He knows he is one of them.

Politics as pacification

Joseph’s description of Indian politics, where corrupt politicians act as “vents for anger so that it does not escalate into something worse,” corresponds to Marx’s notion of the state as “the executive committee of the bourgeoisie.” Populist handouts, spectacle-driven elections, and performative nationalism serve to release social pressure without altering the economic structure.

From a Marxist perspective, Joseph’s worldview is despairingly anti-revolutionary. He does not believe that the poor will awaken to their oppression. “Revolutions,” he writes, “are created by the second rung of the elite to trounce their oppressor.” This is a savage inversion of Marx’s proletarian hope, indicating that in India rebellion is just another bourgeois project.

Readers familiar with Joseph’s fiction (Serious Men, The Illicit Happiness of Other People) will recognise his trademark combination of journalistic realism and biting irony. His prose is surgical. His humour, though dark, is not nihilistic. It seeks to puncture pretence rather than to mock pain.

Joseph writes as an insider, both victim and beneficiary of India’s inequality. He writes from the uneasy vantage point of one who escaped, a man conscious that his comfort rests on another’s deprivation.

The verdict

Joseph’s argument is that peace in India is born of exhaustion, fear, and distraction. The poor do not rise because they are busy surviving and so the rich sleep soundly because inequality itself has been normalised.

This is not a comforting book. It does not redeem anyone, least of all the author. But it is one of the few recent works of Indian nonfiction to treat the country not as a democracy in crisis or an economy in transition, but as an anxious, adaptive, and absurdly resilient organism.

In the end, Joseph offers neither hope nor despair, only the brutal clarity of observation. That, perhaps, is the most honest service a writer can perform in an unequal world.

Publisher: Aleph Book Company

Length: 266 pages

Price: Rs 599

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05