‘I don’t think Indian politics is interested in serious literature’: Khalid Jawed

Khalid Jawed, the winner of JCB Prize for Literature 2022, on finding new metaphors in the kitchen in his award-winning book and how the intelligent readers of Urdu are vanishing

Khalid Jawed (Pic Credit: JCB)

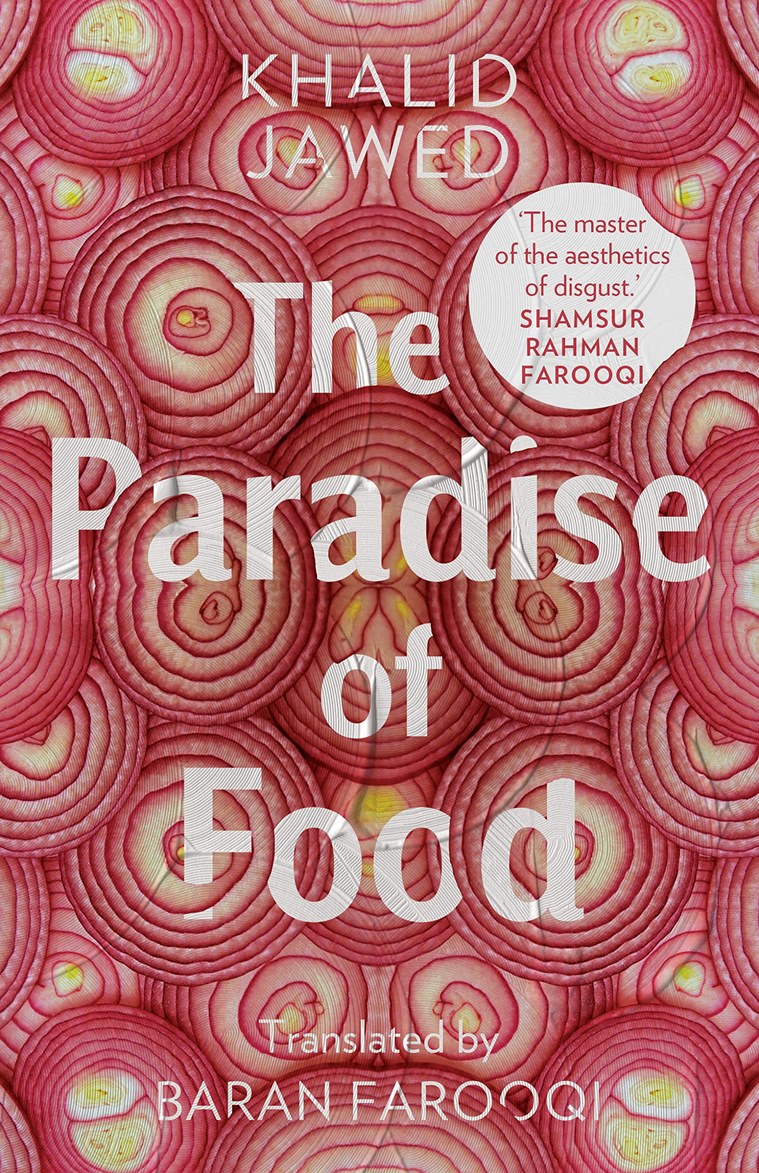

Khalid Jawed (Pic Credit: JCB) Paradise of Food (Rs 799, Juggernaut) winning last year’s JCB Prize for Literature was a landmark moment in the history of the prize. One of Urdu literateur Khalid Jawed’s most popular works, translated into English by his colleague at Jamia Millia Islamia, Baran Farooqi, it was part of a shortlist that was entirely translations, in a year which had already shone much-overdue light on India’s plethora of non-English fiction written post-Independence. With this year’s jury now announced, here are excerpts from a conversation with the author from shortly after his win.

Your book depicts food and the kitchen as sites of disgust, rot and conflict. Why did you break away from their typical representation as spaces of unity, relationships and bonding?

The kitchen is a pure and holy place. When you go in, you take off your slippers and wash your hands. Food is the most important thing to sustain life. But if you think about it, kitchens are also the most dangerous place in the house. All tools in there are weapons too — tong, knife, pan, fire — they help in fighting. This place that we worship has so much violence in it and there’s no other room in the house like that. The Indian middle class, which is the family dealt with in this book, also has a possessiveness about the kitchen. It’s a centre of power, greed, lust — it’s like a battlefield. So I found it works as a metaphor.

Paradise of Food (Credit: JCB)

Paradise of Food (Credit: JCB)

There’s another idea in there. When eating and chewing, you use your tongue, teeth, jaws, which are also used to speak. So I explored another metaphor: could hunger be a hidden universal language?

What was the writing and translation process?

The novel took a year to write. The translation took three to four years, and Baran (Farooqi) initially struggled. She’d say the narrative is very dense and unusual, and we must take care to maintain modern English’s flavour while protecting my own satirical language. We would sit in the park between our department buildings and discuss the translation, and it became a wonderful jugalbandi. A lot can be lost in translation and I firmly believe it’s better to leave something out of a translation than miscommunicate it.

Sometimes we’d talk about how a phrase or word would come across to international readers. We debated on the name of the book too. In Urdu, it’s called Nemat Khana, which doesn’t have a direct equivalent in English. We tried to use ‘pantry’ or ‘cabinet’ but they didn’t work, so we kept the original. The word ‘roti’ confused us too, because it’s often called ‘loaf’ or ‘bread’ in English menus, but that would’ve ruined the flavour of the text. We realised ‘chapatti’ is found on international menus, so would be a suitable alternative. There are many Mughlai dishes in the book too, but no effort was made to explain the difference between Biryani and Pulao.

Where do you situate yourself in the progression of Urdu literature in India?

I draw from the fiction legacy of both the Progressive Writers’ Movement and the Modernist era. The fiction from those times isn’t as popular as the shayari. Everyone knows who Ghalib, Amir, Faiz and Eliya are, but not our Urdu fictioneers. I admire Saadat Hasan Manto, Rajender Singh Bedi, Krishan Chander, Ismat Chughtai, some of whom were in the Progressive movement. I liked that their works were free of naarebaazi (political sloganeering). They made art for art’s sake. From the Modernist era, Intizar Hussain and Qurratulain Hyder influenced me.

Khalid Jawed along with Baran Farooqi, while receiving the prize. (Express photo)

Khalid Jawed along with Baran Farooqi, while receiving the prize. (Express photo)

Both movements are complementary and not without faults. The Modernists used symbolism that was too abstract and subjective, so didn’t communicate easily. I don’t emulate that. The Progressive writers wrote for the downtrodden, mainly the labour class, but there are many other kinds of downtrodden people in society, and fiction has a duty to give voice to everyone, including the ugliness of society. The adjective ‘disgusting’ is often used to describe my themes, and that’s because I want to give disgust a place in the world. I want to allow the unseen tears of the world to flow in my fiction.

According to a Nielsen BookScan study, 55 percent of books sold in India are in English, and 35 percent of Indian language-books are in Hindi. It didn’t have data on the remaining 65 percent because of a “disorganised” market. How have Indian languages gained or lost readers over the years?

The syllabus of schools and universities is 50 years old and hasn’t been changed in decades. This is especially true of Urdu academia. Important developments from the past three decades haven’t been added. Earlier, if a new Urdu novel was released, students and teachers would discuss it. Now, unless it gets an award and becomes popular, nobody notices. It remains a trend. Universities used to produce knowledge, now they just distribute it. The intelligent reader of Urdu is vanishing. The humanities are degrading. Only students who couldn’t do an MBA or engineering or medicine come in to study these languages.

Other languages have a different legacy in India. Every Kannada child recognises Girish Karnad. Every Bengali child knows Rabindranath Tagore and Sarat Chandra, whether they’ve read them or not. They’re like heroes. We have some names like that for shayari but none for Urdu fiction.

Paradise of Food mentions two turbulent moments in Indian history: Rajiv Gandhi’s assassination and the Babri Masjid demolition. Is it easy or difficult to write political literature in India?

I don’t think freedom of expression is hampered in India, though if a writer’s message becomes too loud, they may face opposition. A lot of my work is against religious dogmas, so I often wonder if someone will get upset. Moreover, writers are just not noticed much in India anymore. When Marquez wrote something in Latin America, Fidel Castro felt accountable, because he was a reader. I don’t think anyone in Indian politics today is interested in serious literature.

Serious literature always challenges you, so can invite opposition from anywhere. But a writer should not care too much about it, they should write what they are born to write. Some opposition can come from, say, a Dalit community, if I write a story about a Dalit person; it can conversely annoy an upper-caste person. If I write a woman’s story, a feminist group may deconstruct it and say I’ve only written about the city woman and not the village woman, or a Hindu woman’s experience and not a Muslim woman’s. If you look at the queer community, the way they are regarded has changed a lot now. If I write a gay character and explore their humanity, their joy and sadness, someone may say the way I’ve done it is immoral. There are so many viewpoints now, you can’t make everyone happy. A writer has to take a stand somewhere.

📣 For more lifestyle news, follow us on Instagram | Twitter | Facebook and don’t miss out on the latest updates!

Photos

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05