How immigration fears started the Satyagraha movement

An Indian man went to South Africa at the same time as Gandhi, witnessing the birth of his non-violent tactics of protest. After years of research, his great-granddaughter, journalist Amrita Shah, found out the story of their meeting

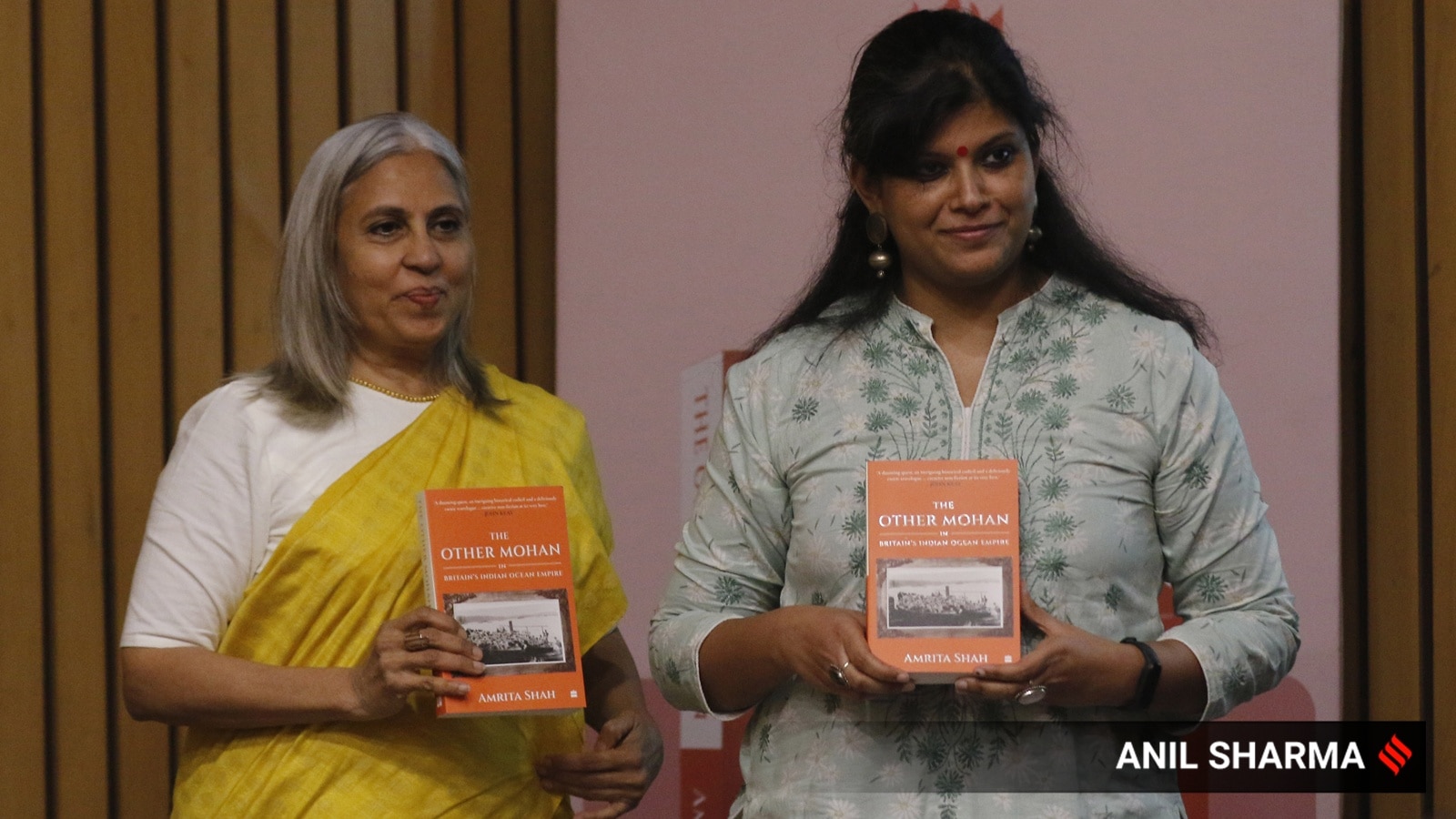

Author Amrita Shah and historian Narayani Basu during Amirta's book launch function in New Delhi (Express photo by Anil Sharma)

Author Amrita Shah and historian Narayani Basu during Amirta's book launch function in New Delhi (Express photo by Anil Sharma)Few admit it, but all families want to be handcuffed to history. Journalist Amrita Shah suspected something similar when, growing up, she heard stories of her great-grandfather setting sail to South Africa around the same time as another educated, aspiring Indian, one who would go on to become the father of a nation. Mohanlal Killavala shared more than part of his name with Gandhi — he ran in the same circles, was mentioned in the newspaper launched by the young barrister to advocate for Indian causes in South Africa, and was part of the crowd that burnt identity documents to protest a racist immigration law, memorialised in a climactic scene in Richard Attenborough’s Gandhi (1982).

But that scene, though vivid, was completely inaccurate, said Shah, laughing, at the launch of her book The Other Mohan In Britain’s Indian Ocean Empire (Rs 699, HarperCollins) last week, the tale of how she overcame her initial scepticism of her great-grandfather’s proximity to Gandhi and embarked on a 10-year-long journey to find out why he left India in the first place and whom the woman was that he married on the way. She was in conversation with historian Narayani Basu.

The story began at the turn of the 20th century. Indentured labourers were being shipped from British colonies to countries like South Africa and Mauritius — particularly from the strip of Indian land encompassing erstwhile Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Orissa and Tamil Nadu. Meanwhile, another class of travellers, known as ‘passenger Indians’ — traders, shopkeepers, businessmen, mostly from Gujarat — followed, lured by the prospect of enterprise, capable of using their education to pay for their tickets, bring their families along and rise up the social ladder. Mohanlal was one of them.

“My great-grandfather would have belonged to this group of professionals because he was educated, he could speak English, and my relatives told me that after he came back, they remembered he was proficient in languages and used to teach Westerners in multinationals. This is where he would have belonged,” said Shah, adding, “Gandhi was, of course, the most well-known and celebrated passenger Indian of the time.”

But how did she find proof? There was little documentation back then, and vague recollections from her family members wouldn’t suffice. When Shah started digging, she found Enugah Reddy, a Gandhi scholar who had come across Mohanlal’s name in an obscure paragraph from Indian Opinion, the newspaper launched by Gandhi in South Africa, dated August 1908: “(He is) an interpretor and teacher in Natal [a South African region] formerly a government servant in India. He had a passport issued to him in Mauritius, in His Majesty’s name, entitling him to proceed to and travel anywhere in British South Africa…”

“From nothing, I now had this wealth of information. I had a time frame, I had a route. I didn’t know he had gone by Mauritius, that he was an interpreter,” said Shah. “And I found, in Indian Opinion, Mohanlal’s name mentioned at some social events [in Natal]. So very quickly he becomes, you could say, the local socialite… Later I found that he was involved in an episode in the Satyagraha campaign.”

Shah argues that this movement, which remains in popular Indian memory as a peaceful protest led by Gandhi against British colonisation, is actually rooted in the “murky business of crossing borders” — one that remains politically relevant today. She mentioned how Gandhi’s arrival in South Africa in 1893 coincided with a slew of laws limiting Indian immigration due to fears of overpopulation, one of which included registering Indians’ fingerprints when entering South Africa.

Author Amrita Shah and historian Narayani Basu with the book (Express photo by Anil Sharma)

Author Amrita Shah and historian Narayani Basu with the book (Express photo by Anil Sharma)

“Fingerprinting at that time was done only for criminals in India. The Indian community protested, saying, we are not all criminals, we are not going to give our fingerprints. This law was really draconian. You had to allow the police to come and search your home at any time, you had to show these identity documents,” said Shah.

“This was the birth of the Satyagraha movement, actually,” she added. “When this law was proposed in 1906, Gandhi starts evolving the idea by 1907 and 1908 of Indians courting arrest, going to jail deliberately because they’re breaking an unjust law.” Moreover, the same Indian Opinion piece from August 1908 proves Mohanlal’s presence at one of these protest sites. “Mohanlal was there when [protestors were] burning their identity papers. He and a few others… refused to register fingerprints. While they waited to be arrested… they went house-to-house, collected identity papers for public burning.”

And what of Shah’s great-grandmother — Mohanlal’s wife? It was another stroke of luck — aided by laborious research in crumbling archives and the unusually meticulous paper trail left behind by corrupt immigration offices. Shah found her way to a long form designed by an immigration officer to be filled by passenger Indians. In 1908, as Mohanlal travelled from the South African regions of Durban to Cape Town, he filled one of these forms. “Thanks to that form, I found out a lot of things,” said Shah. “He had travelled with a wife and child, who would have been my two-year-old grandmother. It gave me my great grandmother’s name, which was really overwhelming for me, because that was the first time we had seen it.”

Photos

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05