Dhirendra K Jha explores the rise of the RSS under MS Golwalkar in his new book

Jha argues that Golwalkar’s ideology was rooted in a deeply exclusionary conception of national identity, where religious minorities, particularly Muslims, were viewed as potential threats to Hindu cultural supremacy

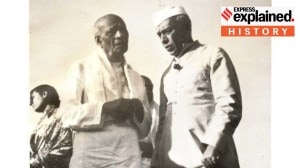

Jha traces how Golwalkar’s philosophical framework provided legitimacy to a narrow understanding of nationhood (Express archive)

Jha traces how Golwalkar’s philosophical framework provided legitimacy to a narrow understanding of nationhood (Express archive)When future historians write of the contemporary epoch, they will have much to sift through. This is because of the fundamental shifts in the sensibilities and makeup of our institutional and everyday life as a national community. Historical epochs are not only marked or identified by spectacular events and visible changes but also the slow grind that chips away at the sense of place, identity, and relations settled over centuries. On December 6, 2024, I was rereading historian Mukul Kesavan’s Secular Common Sense and found that its conclusion reflected perfectly what I was trying to work through while writing my occasional newspaper articles. Writing in 2001, Kesavan observes that “the demolition of Babri Masjid (and its attendant horror) was exceptional. The construction of the Ram Mandir where the Sangh Parivar wants it built won’t lead to apocalypse. The world will look the same the morning after, but the common sense of the Republic will have shifted. It will begin to seem reasonable to us and our children that those counted in the majority have a right to have their sensibilities respected, to have their beliefs deferred to by others. Invisibly, we shall have become some other country”.

We have not arrived where we have — ruthless and violent majoritarian politics, propped up by aggressive crony capitalism, and given a season’s pass by the watchdog institutions of our democracy — by voting or not voting or winning or not winning a particular election. We have arrived here because we were perhaps not very careful in addressing the contradictions of our society —inequality, discrimination, and uneven development—and ignoring the forces that have undermined and disrespected the audaciously progressive social contract we entered right after Independence. While the former is a question of macroeconomics, governance, and, of course, politics, the latter is about how we let down our society by not being vigilant against the corrosive and hollowing ideology of Sangh Parivar, its chequered history of collusion with the colonial oppressors and undermining of the freedom struggle and dalliances with European fascist movements. It was home to cadres conspiring assassinations of leaders who advocated fraternity. The RSS was also banned briefly. The constant attempt to obfuscate and rewrite this troubling origin is a common Sangh Parivar tactic. There is no other way it can manage its multiple internal and external contradictions.

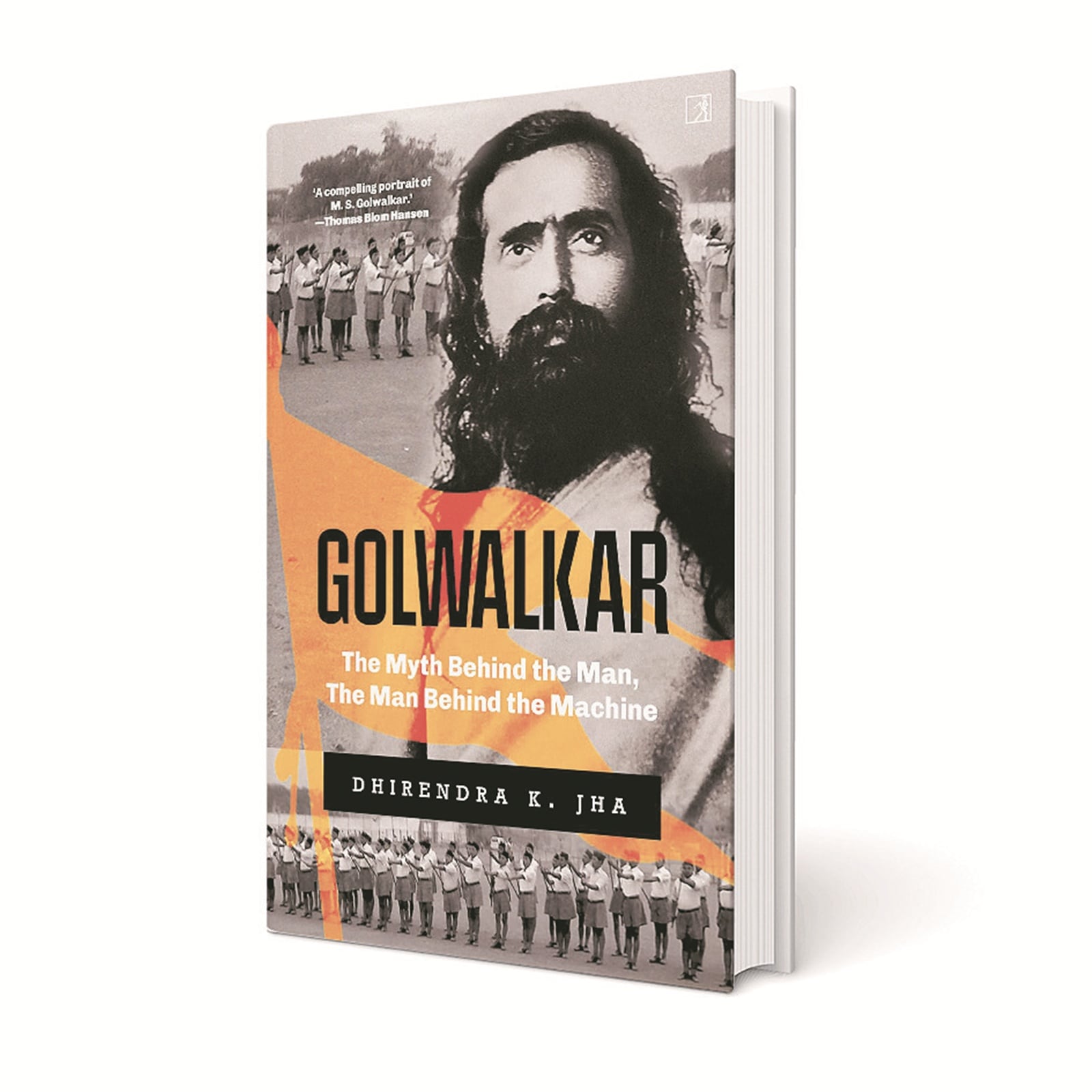

Golwalkar: The Myth Behind The Man, The Man Behind The Machine by Dhirendra K Jha. Simon and Schuster. 416 pages, Rs 899. (Source: Amazon.in)

Golwalkar: The Myth Behind The Man, The Man Behind The Machine by Dhirendra K Jha. Simon and Schuster. 416 pages, Rs 899. (Source: Amazon.in)

A new book by veteran journalist and writer Dhirendra K Jha excavates this aspect of the Sangh Parivar through a well-researched, exhaustive, and accessibly written biography of one of the men who helmed it for over three decades, MS Golwalkar. Jha argues that Golwalkar’s ideology was rooted in a deeply exclusionary conception of national identity, where religious minorities, particularly Muslims, were viewed as potential threats to Hindu cultural supremacy. He meticulously traces how Golwalkar’s philosophical framework provided intellectual legitimacy to a narrow, ethno-religious understanding of nationhood. He paints a sobering portrait of the man who built Sangh Parivar into a surreptitious yet influential “grassroot” movement that was able to capture state power after years of smokes and mirrors, and clawing spaces in neighbourhoods, worker unions, universities, and beyond.

In his previous writings, Jha has explored the genealogy of Hindu right-wing ideology, tracing its philosophical and organisational roots. His work stands out for its rigorous research. In this book, Jha draws from a variety of primary sources — collected papers, national and state archives, and interviews — and secondary sources such as biographies. Some of the best parts of the book are where he demonstrates the poverty of the uncritical pro-Sangh Parivar scholarship—or for that matter even liberal-centrist scholarship —devoted to window-dressing or ignoring the Sangh Parivar’s shortcomings and contradictions. He demonstrates that contrary to popular perception, thanks to myth-making around his circumstances of birth and intellectual prowess, Golwalkar was an unexceptional student with middling achievements at school and college. As widely claimed, he was not a professor at the Banaras Hindu University but a laboratory demonstrator.

Another revealing instance is where Golwalkar comes across as fearful of the colonial government when he discovers his friend, Baburao Tailang, had publicised his favourable views on a political assassination carried out by Indian revolutionaries. Such contradictions — lurching between false bravado and pusillanimity — characterise not only the man but the organisation he fashioned in his image.

One key controversy around Golwalkar and Sangh Parivar has been the authorship of the incendiary We or Our Nationhood Defined, published in 1939. It is where he advocated emulating Hitler’s anti-Semitic programme with the minorities in India. Golwalkar and the organisation began to distance themselves from it, especially after the assassination of Mahatma Gandhi in the face of public fury and government crackdown. Golwalkar went as far as to say in a public address in 1963 that he was not the author of the book, and that it was a shorter, translated version of a Marathi book. Jha notes that the subsequent silence from the Sangh Parivar around the book or its efforts to underplay or refute Golwalkar’s authorship of it, emanate from being embarrassed about acknowledging the influence of Nazism on its ideology.

This Janus-faced character of both the man and organisation is a running thread across the book. Take for instance the contradiction in the Sangh Parivar’s claim of cultural nationalism versus its actual political practice. While claiming to represent an inclusive “cultural nationalism”, the ideology fundamentally relies on an exclusionary definition of national identity based on religious parameters. This approach directly contradicts the secular, pluralistic foundations of the Indian constitutional framework. Another critical contradiction emerges in the Sangh Parivar’s stance on caste. Despite claiming to represent a unified Hindu identity, the organisation has historically maintained complex, often contradictory positions regarding caste hierarchies. While rhetorically advocating for Hindu unity, its organisational structure often reflects and reproduces existing caste distinctions.

The most compelling biographies engage in deep contextual analysis, situating the subject within broader historical, social, and political landscapes, and of course, present the analysis in an accessible form. In this book, Jha has achieved all of this and much more.

The writer is MP (Rajya Sabha), Rashtriya Janata Dal

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05