‘Ashoka was a king who was strong enough to be able to say I am sorry’: Patrick Olivelle

The academic on writing about the dichotomies of the Mauryan ruler and his enduring appeal

Patrick Olivelle (Harper Colins)

Patrick Olivelle (Harper Colins)In a 2002 essay, Lives in need of authors, historian Ramachandra Guha wrote of the Subcontinent’s inadequacy in writing biographies of heft: “In contrast to the art of the novel, the art of biography remains undeveloped in South Asia. We know how to burn our dead with reverence or bury them through neglect but not to evaluate, judge or honour them. Newspaper obituaries are little more than listings of dates and positions, so-called ‘definitive’ biographies recitations of achievements with little reference to context. This is a world governed by deference, not discrimination.”

A good biographer, he said, needed the “instincts of a sleuth” — “… a nose for smelling out hidden documents and a flair for persuading people to part with them. He must have the staying power of the historian, the willingness to read and take notes from millions of words written in shaky and indistinct hands and lodged in dark and distant archives. Last but certainly not the least, he must display the imaginative insight of the novelist, the ability to turn those years of source-finding and note-taking into a compelling and credible narrative”.

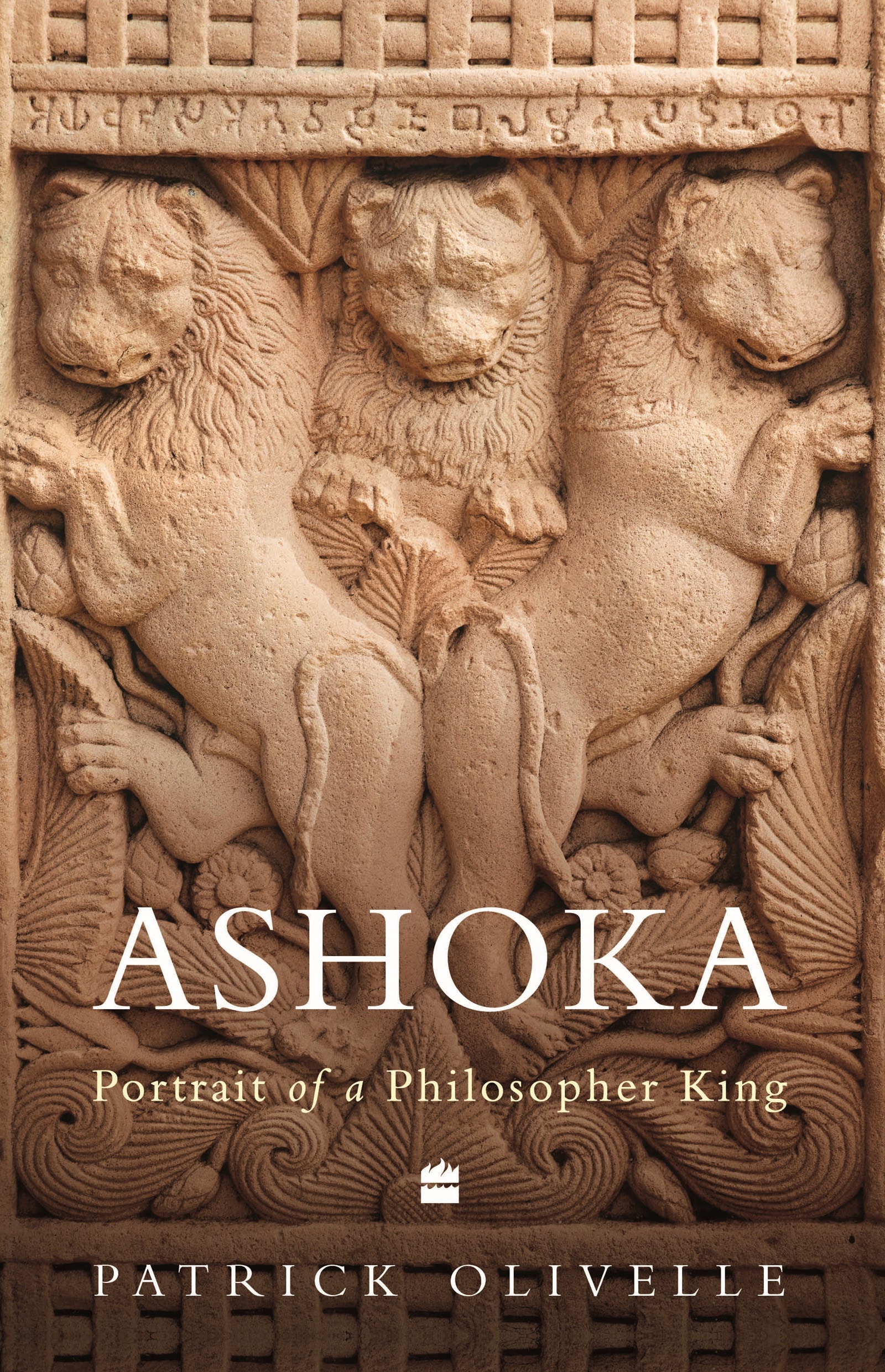

Over two decades later, Guha is the series editor of Indian Lives, a set of 10 biographies to be published by HarperCollins India, that probes the larger history of the Sub-continent through examinations of personal legacies. In the first book of the series, Ashoka: Portrait of a Philosopher King (Rs 799), academic and author Patrick Olivelle, delves into the life of Ashoka and his larger-than-life imprint on India’s political life. In this interview, Olivelle speaks of what drew him to Ashoka, the dichotomies of the Mauryan ruler and why he continues to fascinate. Edited excerpts:

What drew you to the project? What about Ashoka appealed to you the most?

What drew me to study Ashoka over 20 years ago was the fact that I saw him as a pivotal figure in analysing and understanding the early history of Indian culture. I thought of Ashoka as the unseen presence in much of what was happening in the centuries before and after the turn of the millennium. Recent scholarship has also found him to be the subtext of major books of the time, including the Mahabharata and theRamayana. To turn to my book specifically, I think it is the first to present the portrait or persona of Ashoka as it emerges from his own writings in the form of rock and pillar inscriptions. We have the advantage of being able to read them in the very same form in which they were originally written. This is very rare in ancient Indian history.

Ashoka: Portrait of a Philosopher King (Source: Harper Collins)

Ashoka: Portrait of a Philosopher King (Source: Harper Collins)

In the aftermath of the Kalinga war, the idea of the penitent, pacifist, almost-democratic king has come to us through school textbooks, from writings of people such as Jawaharlal Nehru and Romila Thapar. How was Ashoka viewed by people closer to his time, especially by people from different religious communities? What historiographic texts do we have in support of this?

This question is difficult to answer because we do not have reliable independent sources from the period apart from Ashoka’s own inscriptions. So, we can only speculate. We see how Ashoka wanted to be viewed, but not how the other side viewed him. There is virtual silence in the records we possess from the third century BCE when Ashoka ruled.

School textbooks, and even scholarly writings, often do not clearly separate the Buddhist hagiographical information about Ashoka’s life and activities from what can be historically determined. That the aftermath of the brutal Kalinga war left a deep impression on Ashoka is clear from what he says in his 13th Rock Edict. He was deeply affected by the scale of human suffering the war unleashed, and he was deeply remorseful for what he had perpetrated. As I say in the book, he was a king who was strong enough to be able to say: ‘I am sorry’. But the sources do not permit us to draw the conclusion that his remorse made him a pacifist. It is true that he wanted his children not to engage in wars of conquest. But he does refer to his own power in maintaining order within his own kingdom. Although he was committed to the virtue of ahimsa, not killing living beings, he did not abolish the death penalty for serious crimes.

What lessons from Ashoka’s life can powerful modern governments inclining towards authoritarianism imbibe?

I do not think that a scholarly biography should seek explicitly to provide a roadmap for the present. What a biographer hopes is that public intellectuals and activists can draw inspiration from a well-written biography as they work to shape the present culturally and politically. I have drawn attention to what I have called ‘Ashoka’s ecumenism’, something other writings on Ashoka have not. Ashoka asks the numerous philosophical and religious groups of his time, the ones he called Pasandas, to be open to and live harmoniously with each other, to meet and learn from each other. He firmly believed that no one had a monopoly on truth and virtue. Ashoka says that the most important thing that members of Pasandas should do is to control their tongue. Intemperate and vituperative speech causes more harm than anything else. This may be a lesson modern society, including political parties — the modern Pasandas — can learn from Ashoka. There is something we can learn from everybody.

Ashoka’s visit to the Ramagrama stupa Sanchi Stupa 1 Southern gateway (Wikimedia Commons)

Ashoka’s visit to the Ramagrama stupa Sanchi Stupa 1 Southern gateway (Wikimedia Commons)

How was your experience of writing the biography? Do you see yourself writing more of them?

I think my book on Ashoka was the most enjoyable writing project I have undertaken over the past half a century during which I had written exclusively scholarly books. Writing to a different and non-scholarly audience presented challenges, but it was also satisfying and even joyful. I am now 81 years old. So, I am not sure whether I will turn to long-form writing anytime soon. I am looking now at shorter pieces for the general public interested in ancient Indian culture and history.

Photos

- 0116 hours ago

- 021 day ago

- 031 day ago

- 0416 hours ago

- 051 day ago