Workin’ Man Blues

In the industrial areas of the National Capital Region, life is tied to the assembly line. But even if rarely, workers clear a space for that which seems impossible: thought and contemplation, and even the artistic life.

Lal Vachan (standing) performs at a Sunday gathering in Mayapuri

Lal Vachan (standing) performs at a Sunday gathering in Mayapuri

When the whir of engines and the clang of metal against obstinate metal die down, when the neon lights go down in hundreds of sooty factory buildings in Haiderpur, Ashish Kumar opens his notebook. A lanky, dark-skinned, 16-year-old factory worker, Ashish sits down to write at night, “mood banake, aaste aaste”.

In the cramped tenements housing thousands of workers in northwest Delhi’s factories, there is little time or energy or the “heart” to think about life beyond.

But Ashish, who lives in one such tenement cluster in the urban village of Haiderpur with his parents, has not reconciled himself to the mind-numbing tedium of work on the assembly line. He pursues his education through a distance-learning programme offered by the CBSE for students of Class IX and X, plays cricket for a team in the HPL (Haiderpur Premier League), a hyper-local version of 20-20 cricket, and writes at night.

“I love writing at night when there is no studying to do and my parents are not bothering me,” says Ashish, who has changed three factory jobs in the last three weeks, the last one entailing an acid wash of metal containers. He was fired when he refused to dip his hands into a diluted acidic solution. While he makes roughly Rs 250 a day, he resents the bullying of factory owners. Often, he talks back.

His parents, Scheduled Caste Paswans from UP’s Unnao district, moved to Delhi five years ago in search of regular wage labour. Ashish’s mother is a housewife and his father now sells ice-cream off a push-cart. His parent could not afford to spend Rs 1,500 on his tuition classes and books, forcing him to discontinue school and join a correspondence course this year. Ashish’s relationship with his parents has not been smooth, especially since he began “reading a lot” out of a small library run by a trade union nearby. They do not know Ashish writes.

WATCH VIDEO

“I have been reading comics, joke books and stories since the age of eight, spending my pocket money to buy books. But now I read serious things like the fact that every human being is equal. And when I say that to my parents, they get angry. My father was bent on taking me to a godman to get me exorcised. I refused,” he says.

He opens his notebook, gloved in a starry blue cellophane wrap, and begins reading some of the couplets he has composed. “Har subah ki dhoop kuch yaad dilati hai/Har phool ki khushboo ek jadoo jagati hai/Chaho na chaho kitna bhi yaad/ Har mor par aap ki yaad aa hi jati hai (Every morn’s sunshine reminds me of something/ Every flower’s fragrance ignites a magic/ Regardless of my will and mind/ Every bend in the road reminds me of you”. The young man seems to be in love.

He then begins reading Dharam kaisa hai?, a story he wrote a few months back. A mother is angry at her son for having supped at the house of a bhangi, a community of sweepers and beggars from the so-called lower castes. The son asks: “Agar maine ek bhangi ke ghar se khana khaaya to kya mai bhangi ho gaya? (If I eat at a bhangi’s house, do I become one?)”. His mother says, yes. He retorts: “Jo bhangi pichle paach saal se hamare ghar se khana kha raha hai, woh Brahmin kyun nahi hua? (Then why has the bhangi, who has been eating at our house for five years, not become a Brahmin?)”

For the thousands of workers in the industrial areas of the National Capital Region, life is tied to the shift, beginning in the morning at 8 and ending 12 hours later. It is an arduous life, with little financial or job security. Away from the demands of the assembly line and squalid housing, leisure is in short supply. But even if rarely, workers clear a space for that which seems impossible: for thought and contemplation, and even the artistic life.

On a Sunday afternoon in west Delhi’s Mayapuri industrial area, Lal Vachan, 45, and fellow workers rest at the MCD park, a small island of green in the grey matrix of factory buildings. Lal Vachan has been working as a factory hand in Mayapuri since 1985. For him, escape from the drudgery of work at an auto-parts factory comes from writing and composing songs. His songs, in Bhojpuri, are about the factory shopfloor and home, the bookends of his life.

WATCH VIDEO

“Din bhar bhaiya kare majoori/ Tap tap chooe pasinva ho/ Tap tap chooe pasinva/ Ghar aile bhar pet na mile bhojanwa larka rowe/ Ghar anganwa sukh sapanwa bhaiya na (All day long, brother, I toil/ Drop by drop, I sweat it out oh/ Drop by drop I sweat it out/ Yet when I go back home, my boy weeps over a half-empty stomach/ My home is devoid of happiness and dreams),” he sings in his full-throated voice.

An editor distributes copies of the Faridabad Mazdoor Samachar

An editor distributes copies of the Faridabad Mazdoor Samachar

“Art and creativity has always been there (in wage workers). It becomes a way of expressing and experiencing freedom from back-breaking labour and poor working and living conditions. Only, it never comes to light because it is known in smaller circuits,” says Sudhanva Deshpande, actor and director with Jana Natya Manch, a Delhi-based theatre company.

Lal Vachan writes his songs on the factory shopfloor. “I snatch a few minutes here and there to compose a line and set it to a tune. After the 11kv furnace designed to melt 500 kg of iron by the hour is rested, I begin composing. My first audience is my immediate worker friend. Later, I sing it to my worker friends across Mayapuri. They love my songs,” he says.

Lal Vachan lives with his wife and daughter-in-law in a jhuggi along the railway line. His songs reflect his circumstances and those of the workers around him. “I was not paid my wages amounting to Rs 60,000 for six months back in 2013 by the owner of Karan Motors, the factory I work in. Almost all of us, 140 workers, went to court and the case is pending. Woh zulm karte jaate hain, aur koi hisab kitab nahi hota. (The owners exploit us and no one keeps an account),” he says. All 140 workers continue to work in the factory after a court-mediated settlement.

The Mayapuri industrial area is home to the country’s biggest scrap yard for automobiles and hundreds of small-scale metal forging and auto-part units. It began taking shape around 1975 as the capital’s scrap and furniture markets shifted out of the Old Delhi railway station area and Kirti Nagar, respectively and moved here. Export garments and heavy machine factories followed suit in the 1990s, followed by migrants in search of work.

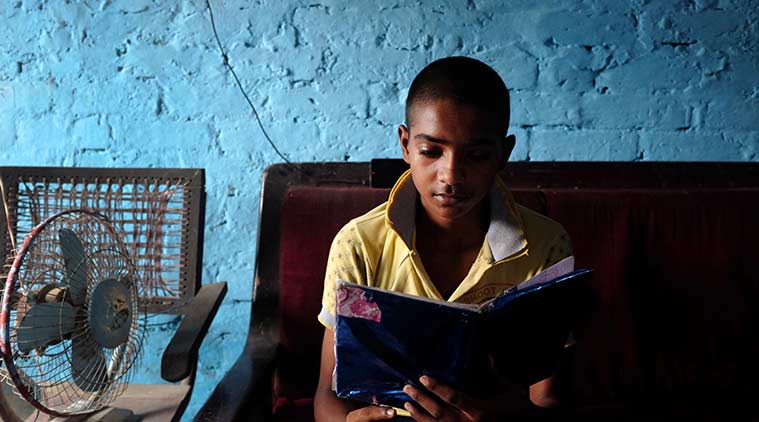

16-year-old Ashish Kumar in Haiderpur

16-year-old Ashish Kumar in Haiderpur

In the early 2000s, as news of accidents, deaths and instances of harassment began to be reported, the Indian Federation of Trade Unions (IFTU) opened a chapter here. This was also the time heavy industries moved out of Mayapuri to Bahadurgarh and Manesar on the fringes of the NCR, making way for hundreds of smaller textiles, utensil and auto-part units, which employ roughly 100 to 200 workers each. Today there are roughly 1,800 factory units in Mayapuri.

Rajesh Kumar, general secretary of IFTU’s Delhi committee, who convinced Lal Vachan to join the union when the workers filed the court case, says, “We keep an eye out for higher minds like Lal Vachanji who are popular among their co-workers. Their songs, their stories and plays are a potential media for broadening worker consciousness.”

The worker on the assembly line has inspired films such as Charlie Chaplin’s Modern Times and the music of Pete Seeger. Much earlier, French philosopher Jacques Ranciere’s seminal work Proletarian Nights celebrated the writer-worker of the French working class during the revolution of 1830. He wrote about the worker-writer who rises above his proletarian lot by thinking and writing, radical acts in themselves by virtue of being exercised by workers who were otherwise “destined” to plod away at mindless, alienating labour. Ranciere re-evaluated the working class as not merely a wretched lot clamouring for better wages and work conditions but also one comprising an aesthetically conscious few who want an alternate life, without the “daily theft of their time”. He discovered workers who reclaimed the nights from the cycle of work and sleep to write, discuss, keep journals and circulate newspapers — acts which brought them closer to the intellectually mobile bourgeoisie class “endowed with the privilege of thought”.

Worker newspapers and journals have been thriving in industrial regions of the Delhi-NCR as well. They chronicle protests on factory shopfloors, court cases lost and won, happenings around the world, one’s engagement with time and life. The latest issue of the Faridabad Majdoor Samachar, a paper started by workers and activists in the 1980s, for instance, opens with an article titled ‘Sunday Sangharsh’ or ‘Sunday Struggle’.

Ashish pursues his education through a distance-learning programme offered by the CBSE for students of Class IX and X, plays cricket for a team in the HPL.

Ashish pursues his education through a distance-learning programme offered by the CBSE for students of Class IX and X, plays cricket for a team in the HPL.

It reads thus: “Uncle, have you heard of the latest invention: the Sunday struggle?” a youth begins. “It’s the day leaders want workers to stage hunger strikes, gather outside government offices, distribute pamphlets and oppose the dictatorship on shop floors.” The older worker clarifies, “You mean on the weekly off?” The youth says, “Exactly! Production stays safe. Companies stay safe. Officials stay safe. Nothing is harmed, no one is rankled.”

“Sunday struggle is a metaphor for all the hindrances invented and manufactured by factory owners to keep workers from agitating,” an editor of the monthly workers’ broadsheet says, as he opens the door to the Faridabad Majdoor Library, which hosts brainstorming sessions among workers, writers, artists and friends. “A worker told me about it and I put it down as the opening story in the current edition.”

It is 7 am on a Friday. The editor, who does not want to be named, is armed with an umbrella, a notebook and a pen. He anchors himself outside the office of a telecom giant in Gurgaon’s Udyog Vihar for his weekly session of baat-cheet. He also carries copies of the latest issue of the Samachar which is distributed gratis to whoever is interested.

Baat-cheet and taal-mel are informal modes of communication that involve sharing ideas and stories before or during shift hours outside factory buildings. The anecdotes fill up the pages of the Samachar, which currently has a circulation of 16,000 in Okhla, Gurgaon, Faridabad and Manesar.

An ocean of men and women, mostly migrants from Bihar and UP, flows through the bylanes of Udyog Vihar from the nearby urban villages of Kapashera and Dundahera for three hours between 7 am and 10 am. “What happened? When will my story appear?” Bablu, a tall haggard man walks up to ask. His wife, he says, has been working late into the nights in one of the factories in the area. “I am worried. I do not know why the owner keeps women working so late,” he says. Some come up for their copy of the Samachar while others come with stories of bekari, overtime without pay, landlords in Kapashera who charge Rs 200 for each “extra” child beyond the mandated two as part of the rent agreement.

Most of those who linger around for a copy of the Samachar are looking for work. Sonu Kumar, a worker in the export textiles industry, recently found out he was no longer needed at work when he returned from a short visit to Chhapra, Bihar, because his mother was ill.

“I took the supervisor’s permission. But I came back and saw my former colleague hired in my place. Everything is so fluid and temporary in the labour market. No one survives a work stint more than a year because the owner will fire you on some pretext or the other. Today, it’s down season in the export market and workers are not needed, tomorrow Diwali is nearing so factory owners lay off people by the horde to avoid paying bonus and then there is the bogey of the factory being shifted to Manesar,” Sonu says.

The newspaper not only records reports on lockouts, and international labour law violations or reforms, it also features short exchanges, aphoristic ruminations on how one sees life, time, work and rest.

Vipin, a 21-year-old who desperately wants to get out of factory work for good, is a regular contributor to the Samachar. “I am studying to clear exams for admission into a power supply company,” he says.

His stories offer a glimpse into the opaque logic of the factory. One of them, titled Behrupi Akritiyon ki Pratidhwani, or ‘Polymorphic Resonances’ (the English translation can be read online on the blog of the Faridabad Majdoor Samachar) talks of how free will spontaneously expresses itself on the “surreal” shopfloor.

He describes an instance of fellow workers rebelling against forced excess production — by finishing work before time. “That day there was no meeting. There were no hushed conversations. No one called others for discussions. Everyone was calm and quiet. The thought of stopping work and cleaning one’s hands 45 minutes before lunch hour came to each one on the shop floor. Was it magic? This happens often. Once or twice a month.”

Photos

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05