© IE Online Media Services Pvt Ltd

Latest Comment

Post Comment

Read Comments

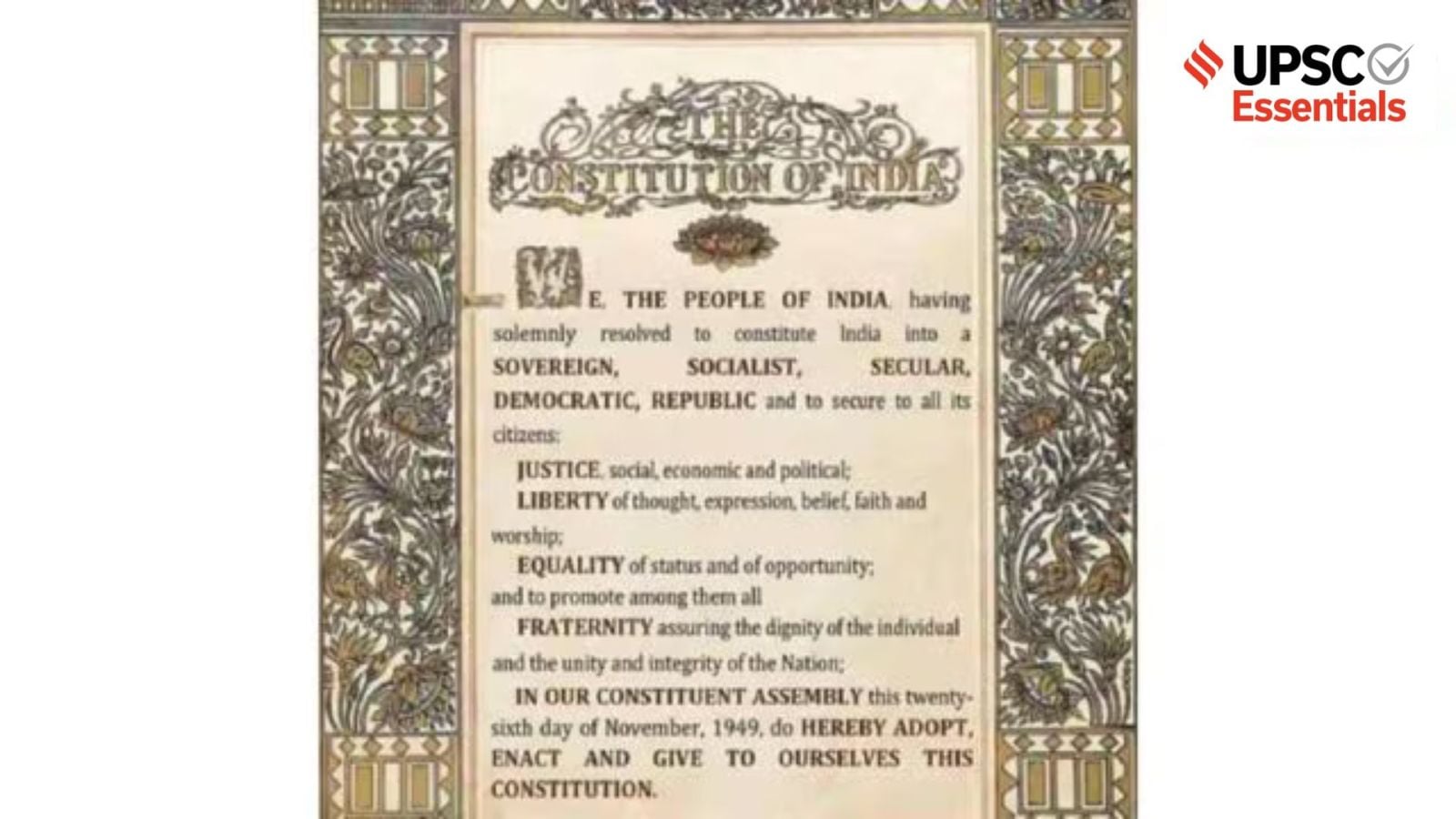

The first and foremost task for the leaders of independent India was to consolidate and strengthen the nation’s unity. How did they do this? (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

The first and foremost task for the leaders of independent India was to consolidate and strengthen the nation’s unity. How did they do this? (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)— Dileep P Chandran

In 1947, India commenced its long journey to overcome the legacies of colonial rule, such as centuries of economic stagnation, weak political institutions, undemocratic governance, fragmented polities, widespread illiteracy, westernised education, social inequalities, and pervasive poverty.

In addition, the partition of British India and the communal tensions that accompanied decolonisation further compounded the challenges of nation-building, as well as fulfilling promises made during the freedom struggle.

The first and foremost task for the leaders of independent India was to consolidate and strengthen the nation’s unity by recognising the regional, linguistic, cultural, and social diversity of its vast population and by preparing the country for social transformation, economic development, and political unity.

In doing so, building a democratic structure with robust institutions for national integration warranted urgent attention. This was to defy the pessimism of sceptics who had predicted that independent India would collapse and disintegrate sooner or later.

To shape the destiny of its people, independent India required a Constitution framed without any external interference – an idea for which its leaders had bargained with the British even during the colonial period. As early as 1921, Mahatma Gandhi asserted that Swaraj must spring from the will of the people expressed through their freely chosen representatives.

M N Roy was the first national leader to demand a Constituent Assembly to draft the Constitution for independent India in 1934. The following year, the Indian National Congress made this part of its official demands. Despite differences over specific proposals, the Constituent Assembly was constituted in 1946 under the scheme formulated by the Cabinet Mission Plan. The Assembly’s members were partly elected and partly nominated.

It held its first meeting on December 9, 1946, which was attended by 207 of 389 members originally envisaged. The process of Constitution-making extended over two years, eleven months, and eighteen days. The draft Constitution, prepared under the chairmanship of B R Ambedkar, was debated for 114 days in the Constituent Assembly before it was finally adopted on November 26, 1949.

The original Constitution, comprising a Preamble and 395 Articles, came into force on January 26, 1950 – commemorating the Purna Swaraj day first observed on January 26, 1930. Through this long and meticulous process, the framers envisioned India as a sovereign, democratic republic, adopting a parliamentary model of government within a federal structure.

Alongside the Constitution drafting, unifying a fragmented polity with more than five hundred large and small princely states after the partition of British India was yet another test of the statesmanship of leaders of independent India.

Many of the large princely states wanted to remain independent, claiming that their paramountcy couldn’t be transferred to independent India or Pakistan. This sentiment was further encouraged by British Prime Minister Clement Atlee, as he granted them the freedom to become independent states. Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel and V P Menon were tasked with integrating these hundreds of princely states into the Indian Union.

Patel warned Menon, “the situation held dangerous potentialities and that if we did not handle it promptly and effectively, our hard-earned freedom might disappear through the States’ door.” Patel also offered the rulers of princely states privy purses and other privileges in exchange for their accession to the Union.

Political strategies and diplomacy of Patel and Menon persuaded all except Hyderabad, Junagadh, and Jammu and Kashmir to accede to the Indian Union by August 14, 1947. Subsequently, Junagadh joined the Indian Union through a plebiscite, Hyderabad was integrated after military action, and Jammu and Kashmir acceded to India through an Instrument of Accession.

The process of territorial integration was completed when the French authorities handed over Pondicherry in 1954 and Goa was liberated from Portugal following a military intervention ordered by then Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru in 1961.

The political turmoil surrounding the process of integration compelled the leaders of free India to set aside the formation of linguistic states, which was promised during the national freedom movement. However, Potti Sriramalu’s martyrdom after a 58-day hunger strike demanding a separate state for Telugu-speaking people triggered mass protests, and eventually forced Nehru to announce the formation of Andhra Pradesh in 1952.

Following the recommendations of the Fazl Ali Commission, the government enacted the State Organisation Act, 1956, which established 14 states and 6 Union Territories. This reorganisation helped avert the fear of disintegration and preserve national unity.

Political scientist Rajni Kothari observed, “In spite of the leadership’s earlier reservations and ominous forebodings by sympathetic observers, the reorganisation resulted in rationalising the political map of India without seriously weakening its unity.”

Together with process of Constitution-drafting and political integration, attention was also paid to India’s education system. The introduction of colonial education not only sidelined India’s traditional educational system, but it was primarily meant to serve the commercial interests of the East India Company and the clerical needs of the British administration.

The colonial education largely concentrated educational opportunities among the urban upper and middle classes and was heavily focussed on producing clerks and administrators. In doing so, it jeopardised mass education, research potential, and technical and vocational training.

The British administration’s inadequate investment in education and research was also criticised by Indian leadership. After independence, India’s leadership sought to address these issues by establishing robust institutional mechanisms, particularly in the higher education sector. The Constitution, under Article 45, mandated the State to provide free and compulsory education for all children until they complete the age of fourteen years.

The University Education Commission (1948-49) under the chairmanship of Sarvapalli Radhakrishnan was the first education commission of independent India. It recommended a comprehensive reconstruction of the university education system. Similarly, the Mudaliar Commission (1952) recommended developments in the secondary education system.

The establishment of the University Grants Commission (UGC), inaugurated by then Education Minister Maulana Abdul Kalam Azad in 1953 was a major milestone in this regard. Since becoming a statutory body in 1956, the UGC has been responsible for the coordination, determination, and maintenance of standards of university education across India.

To address the gap in technical education, Nehru pioneered the establishment of Indian Institutes of Technology (IITs), beginning with IIT Kharagpur in 1950, followed by four more within the next decade – IIT Bombay (1958), IIT Madras (1959), IIT Kanpur (1959), and IIT Delhi (1961). These institutions of higher education and research were designed to build the strong technological and scientific foundations of modern India.

In addition to strengthening internal foundations, the leadership paid attention to India’s relations with other countries. Notably, India began to engage seriously with British India’s relations with other countries during World War I. It was the original member of the League of Nations and played an active role in the governing body of the International Labor Organisation (ILO). The Indian National Congress articulated a vision for international relations through a resolution in 1921, which later became independent India’s foundational principles of foreign policy.

By the late 1920s, the Congress had a separate foreign policy department headed by Nehru, whose extensive foreign travels and keen interest in international politics considerably shaped the course of India’s future external relations. His leadership in the Afro-Asian Conferences and the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) marked the emergence of India’s significant voice in international politics.

Building upon this historical legacy, the foundational principles of free India’s foreign policy came to be shaped by anti-colonialism, anti-racism, non-alignment, Afro-Asian unity, peace, nonviolence, disarmament, democratic dialogue, cooperation with international organisations, and respect for human rights.

Article 51 of the Indian Constitution directs the State to promote peace and security and maintain just and honourable relations with other nations. The Panchsheel Agreement, signed with China in 1954, further guided India’s peaceful coexistence with other countries.

Trace India’s consolidation process during the early phase of independence in terms of polity, economy, education and international relations?

Discuss the major challenges faced by India in the immediate aftermath of independence in achieving political consolidation and national unity.

Examine the role of Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel and V P Menon in integrating the princely states into the Indian Union.

Evaluate the significance of the Indian Constitution in laying the foundation for a democratic and inclusive polity.

How did colonial education affect India’s indigenous systems of learning and research? Discuss the major recommendations of the University Education Commission (1948–49) and their relevance to modern India.

India Since Independence (2000) by Bipan Chandra, Mridula Mukherjee, and Aditya Mukherjee.

Indian Constitution: Cornerstone of a Nation (1966) by Granville Austin.

(Dileep P Chandran is an Assistant Professor at the Department of Political Science in P M Government College, Chalakudy, Kerala.)

Share your thoughts and ideas on UPSC Special articles with ashiya.parveen@indianexpress.com.

Click Here to read the UPSC Essentials magazine for October 2025. Subscribe to our UPSC newsletter and stay updated with the news cues from the past week.

Stay updated with the latest UPSC articles by joining our Telegram channel – IndianExpress UPSC Hub, and follow us on Instagram and X.

Read UPSC Magazine