World Economic Forum releases guidelines for tackling growing space debris problem

The World Economic Forum and the European Space Agency jointly released a set of guidelines aimed at mitigating the growing space debris problem.

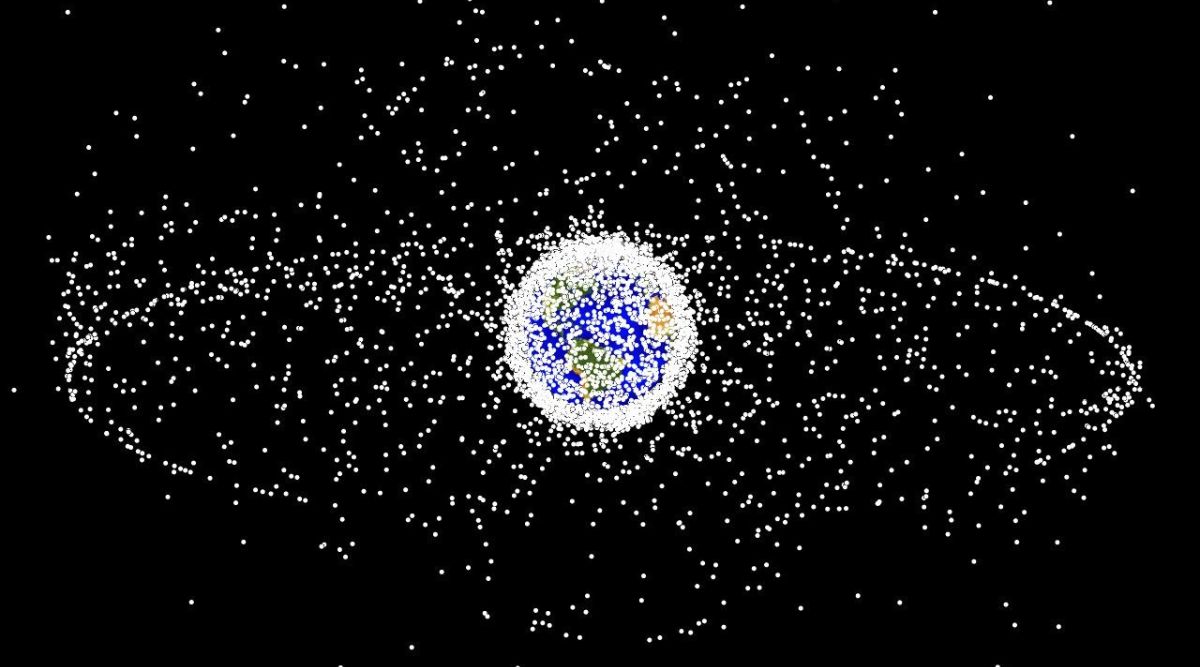

A computer-generated image showing the location of space debris that is currently being tracked. Note that the size of the debris has been scaled up for visibility and is not to scale with the planet. (Image credit: NASA Orbita Debris Program Offiice via Wikimedia)

A computer-generated image showing the location of space debris that is currently being tracked. Note that the size of the debris has been scaled up for visibility and is not to scale with the planet. (Image credit: NASA Orbita Debris Program Offiice via Wikimedia) The world has reaped the benefits of space-based technologies and applications like GPS and others. However, the increasing number of satellites in Earth’s orbit means that we also have to contend with the growing problems of orbital debris and collisions. The World Economic Forum (WEF) on Tuesday released a set of recommendations to mitigate the space debris problem.

Figures from NASA’s Orbital Debris Program Office paint a pretty grim picture of our planet’s orbit—as of January 2022, the amount of material orbiting our planet exceeded 9,000 metric tons. Of the debris in orbit, more than 25,000 objects are larger than 10 centimetres, 500,000 particles are between one and 10 centimetres in diameter and there are more than 100 million particles whose size exceeds one millimetre.

Many of these pieces of debris are flying through space at speeds many times that of a bullet. If one of the larger pieces of debris collides with an active satellite, it could sabotage what could very well be a crucial mission.

The Space Industry Debris Mitigation Recommendations was published by the WEF in collaboration with the European Space Agency to attempt and solve the problem of space debris. The guidelines mainly focus on how not to generate more space debris with the end-of-life operation of satellites and data sharing and traffic management in orbit for debris avoidance.

The guidelines are not exactly rules, and they are, therefore, non-binding. But they are aimed at setting behavioural norms and an example for the entire space industry.

Post-mission disposal

The main focus of the guidelines is on the disposal of satellites after the mission. The guidelines say that spacecraft operators try to get satellites removed from low-Earth orbit within five years after the end of the mission. In case operators are not able to maintain control of the satellite and de-orbit it, they should pursue other proven, reliable and cost-effective technologies to ensure it does not turn into space debris.

s

Collision avoidance systems

Also, spacecraft operators should try to reduce the probability of satellite collisions with the use of avoidance manoeuvres. Missions that orbit above an altitude of 375 kilometres should have an ability to actively manage the orbit. The guidelines encourage a propulsion-based system but other technologies could be more appropriate depending on the situation.

Data sharing and traffic management

This is a tricky one. The guidelines say that all spacecraft operators must answer all (reasonable and legitimate) requests for space traffic management coordination. This could be from other operators or other entities.

Also, every satellite operator should try to proactively coordinate with other operators and entities to create operational coordination agreements and space situational awareness information-sharing. The minimum information to be shared, as suggested by the guidelines, is operator points-of-contact, ephemerides (table of data giving calculated positions of spacecraft), ability to manoeuvre, and manoeuvre plans.

Long-term goals

The guidelines also put down some long-term goals and requests to policymakers. It encourages industry players to further study the objects in orbit—the population, evolution, and the interaction between them. This can help improve space situational awareness capabilities.

While most of the document focused on what can be done by the industry itself, it also lays down some ground rules that can be enforced by various governments. This includes asking governments to require by 2030 that all space missions have capabilities to remove satellites from orbit within five years of the end of mission.