‘One small step for LLMs’: Why training the first AI model in space is a breakthrough

A little-known startup called Starcloud may have just proved that the futuristic concept of space-based data centres is no longer a pipe dream.

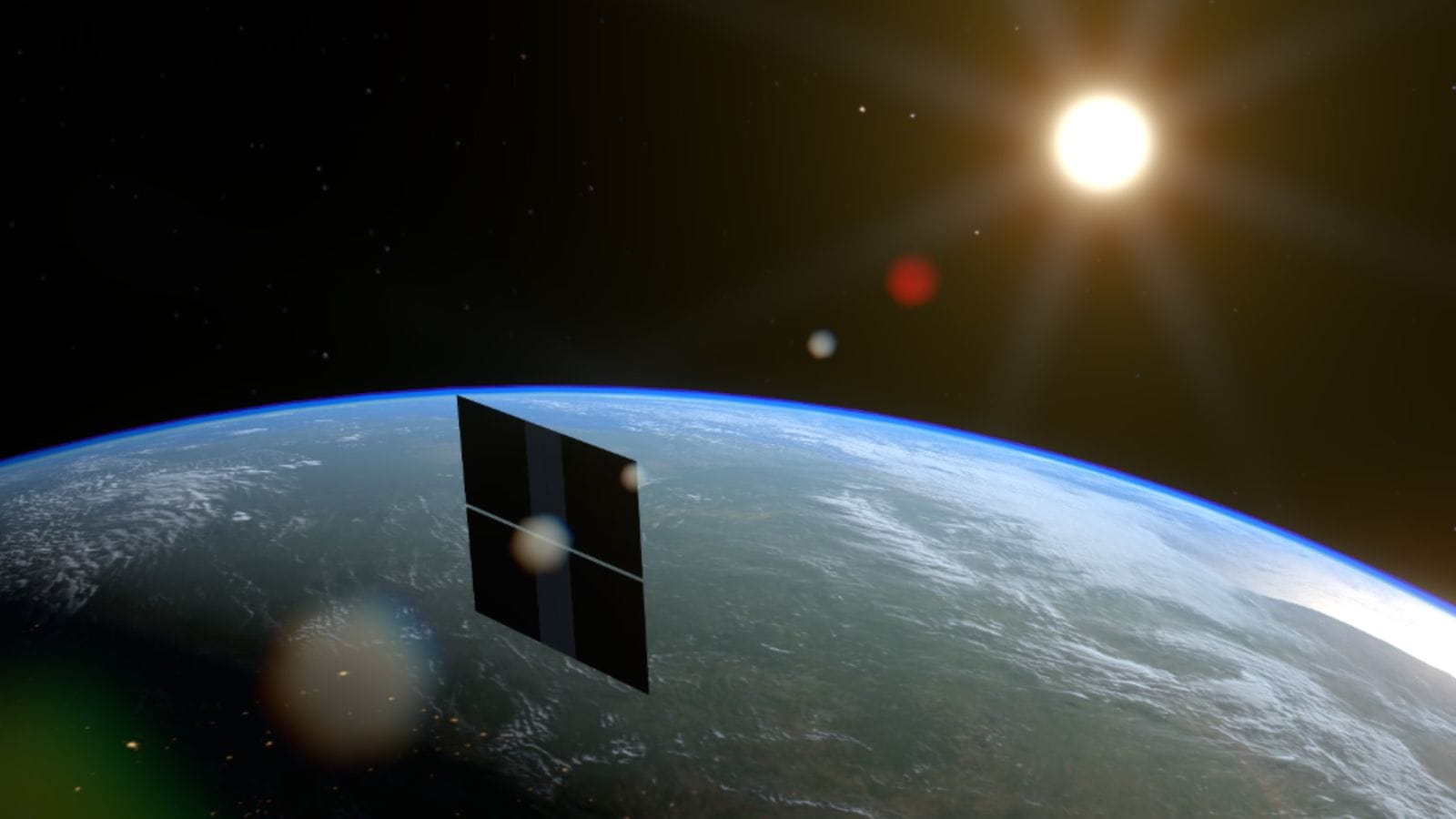

Starcloud plans to build a 5-gigawatt orbital data centre with solar and cooling panels measuring 4 kilometers in width and height next year. (Image: Starcloud)

Starcloud plans to build a 5-gigawatt orbital data centre with solar and cooling panels measuring 4 kilometers in width and height next year. (Image: Starcloud)The history of human spaceflight has come to be defined by messages that have been beamed back to Earth from across the void. From the rhythmic beep of Sputnik 1 to Neil Armstrong’s “one small step…”, these transmissions have marked moments of profound scientific achievement and technological innovation.

The latest entry in this ledger could be an AI-generated note: “Greetings, Earthlings! Or, as I prefer to think of you — a fascinating collection of blue and green,” read the first-ever message from a generative AI model trained using Nvidia hardware aboard the Starcloud-1 satellite launched last month and now circling in low-earth orbit.

The first generative AI model to be run in space is a fine-tuned variant of Gemma, Google’s open-weight small language model (SLM), built by StarCloud – an Nvidia-backed startup that wants to show how outer space can be a hospitable environment for data centres in comparison to enormous multi-gigawatt terrestrial facilities that consume millions of litres of water daily and produce substantial amount of greenhouse gas emissions.

Starcloud’s satellite carries an Nvidia H100 graphics processing unit (GPU) that was used to successfully train and run the Gemma model from space. The model has also been integrated with the satellite’s telemetry sensors measuring its altitude, orientation, location, and speed. This lets users on Earth query the chatbot about the satellite’s location and receive updates such as ‘I’m above Africa and in 20 minutes, I’ll be above the Middle East.’

In addition to Gemma, Starcloud said it used the space-based H100 chip to train NanoGPT, an SLM created by OpenAI founding member Andrej Karpathy, on the complete works of William Shakespeare.

Big tech’s insatiable demand for AI infrastructure is already straining Earth’s resources, pushing tech companies toward out-of-the-box solutions. By demonstrating that AI models can be trained and run on GPUs aboard solar panel-fitted satellites in orbit, Starcloud shows that the science fiction-like concept is not as outlandish as it seems. It could mark the birth of an entirely new industry. Though, there is still a long path ahead and several bottlenecks to resolve along the way.

To note, the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) is also exploring next-gen satellites with on-board data processing and data storage, according to the Centre’s response in Parliament on December 11.

What is the problem with terrestrial data centres?

Terrestrial data centres have a massive energy demand. As per the International Energy Agency (IEA), data centre power usage could double by 2026.

While renewables have been the first choice for companies, there are hurdles posed by green energy — not generating power when the sun’s not shining or the wind is not blowing, and absence of adequate storage options to bridge the shortfalls — that have made fossil fuels the go-to power source.

But this has made tech companies’ goals of becoming net zero or carbon negative by 2030 increasingly unattainable.

As a result, tech giants such as Google and Microsoft have signed deals with nuclear power plants to purchase energy for their data centres. But it may be years before some of these plants become operational.

Why are tech companies pursuing orbital data centres?

The idea of low-earth orbit satellites serving as a new home for AI processing chips is appealing to both tech startups and hyperscalers because they can tap into the limitless energy of the Sun and set up greater, gigawatt-sized operations in space. It could also alleviate a potential crisis on Earth that could result in soaring electric bills, heavy water usage, and other burdens of power-hungry terrestrial data centres.

Starcloud’s orbital data centres will have 10 times lower energy costs than terrestrial data centres, according to CEO Philip Johnston. “Anything you can do in a terrestrial data centres, I’m expecting to be able to be done in space. And the reason we would do it is purely because of the constraints we’re facing on energy terrestrially,” Johnston was quoted as saying by CNBC.

Space-based data centres would be able to capture constant solar energy to run AI processing hardware as they would be not be hindered by the Earth’s day-night cycles and weather changes. There are also potential opportunities to leverage the fact that the speed of light in a vacuum is 35 per cent faster than in a typical glass fibre, Starcloud’s white paper reads.

As concerns mount over AI and terrestrial data centres, the lack of clear regulations governing space-based data centres may be another factor at play.

Who all is in the running to launch orbital data centres?

Founded in 2024 by Philip Johnston, Ezra Feilden, and Adi Oltean, Starcloud has quickly gained traction after joining Nvidia’s Inception programme and graduating from leading accelerators such as Y Combinator and the Google for Startups Cloud AI Accelerator.

The Redmond, Washington-based startup plans to build a 5-gigawatt orbital data centre with solar and cooling panels measuring 4 kilometers in width and height next year. The company has reportedly partnered with Elon Musk-owned SpaceX for the nearly 100 rocket launches required to deploy the entire 5GW data centre in orbit, according to its white paper. Starcloud has raised over $20 million in seed funding, according to Pitchbook, with Andreessen Horowitz and Sequoia Capital as major investors.

Besides Starcloud, several companies have announced space-based data centres missions. Google’s Project Suncatcher aims to launch solar panel-fitted satellites with its custom tensor processing units (TPUs) as payloads in 2027. Musk has indicated scaling up the Starlink constellation with new versions of its satellites equipped with solar arrays, while OpenAI CEO Sam Altman was reportedly in talks to acquire a rocket startup.

A major additional factor should be considered.

Satellites with localized AI compute, where just the results are beamed back from low-latency, sun-synchronous orbit, will be the lowest cost way to generate AI bitstreams in <3 years.

And by far the fastest way to scale within 4…

— Elon Musk (@elonmusk) December 7, 2025

Earlier this year, Lonestar Data Holdings somewhat successfully placed a mini-data centre on the Moon in a test to prove that it can store data off-Earth. It is expected to carry out more launches next year. Similarly, Aetherflux plans to launch an orbital data centre satellite in the first quarter of 2027.

Among Indian space-tech startups, TakeMe2Space is working on building satellites with AI computing capabilities. The Hyderabad-based startup has raised Rs 5.5 crore in a pre-seed funding round led by Seafund. Visakhapatnam-based Taramandal is also exploring modular, small satellite-based compute prototypes.

“These early efforts show that the Indian ecosystem is also gearing up for the next wave of in-orbit technologies,” Lt. Gen. AK Bhatt (retd.), Director General, Indian Space Association (ISpA), told The Indian Express.

What are the risks of running a data centre in orbit?

Orbital data centres could enable better satellite imagery and real-time information that could aid on-ground disaster-response efforts. But maintaining large structures in space is expensive and comes with a host of complex challenges as attested by the International Space Station (ISS).

Data centres do not have to support human life, but they are exposed to harsh radiation and debris hazards requiring in-orbit maintenance.

“Despite advanced shielding designs, ionising radiation, thermal stress, and other aging factors are likely to shorten the lifespan of certain electronic devices,” Starcloud admits. But the positive effects of space such as cooler operating temperatures, mechanical and thermal stability, and the absence of a corrosive atmosphere (except atomic oxygen) may prolong the lifespan of other devices, the company argued.

Overall, Starcloud expects its satellites to have a five-year lifespan given the expected lifetime of the Nvidia chips on its architecture.

ISRO, in its study, also found that while deploying edge computing infrastructure in space is feasible, more research is needed in areas such as in-orbit power generation, radiation-hardened GPUs and CPUs, and security shields for orbiting satellites.

Other issues like upgrades, which are routine on Earth, may become massive engineering problems in space. Launching orbital data centres would further require a tremendous amount of rocket capacity, and the concept is only financially viable after rockets start launching at a high cadence.

While companies argue that these hurdles are not insurmountable, the long-term viability of space-based data centres remains uncertain and heavily relies on the upward curve of AI demand.