The untold story of Karsandas Mulji, the journalist who won the fight against the Maharaj

Karsandas Mulji has recently been popularised by the Netflix biopic Maharaj. In the film he is depicted as a staunch feminist and patriot but the reality is slightly more complicated

The Maharaj Libel Case of 1862 captivated the attention of India and the World

The Maharaj Libel Case of 1862 captivated the attention of India and the WorldMaharaj, a biopic on Karsandas Mulji, a journalist and a social reformer, is currently streaming on Netflix.

Mulji gained fame and notoriety after he accused a religious leader of sexual impropriety. In response, the accused, Jadunath Maharaj, filed a libel case against Mulji, which played out in dramatic fashion within the confines of the Bombay High Court in 1862.

Like its protagonist, the producers of Maharaj were also called before the Gujarat High Court, when members of the Vaishnavite sect objected to the “scandalous and defamatory language” used in the film.

In an instance of the past mimicking the present, both cases were eventually dismissed.

However, while the film portrayed Mulji as an indisputable Indian hero and feminist — the latter critics contest ardently against — the reality is slightly more complex. Mulji was a courageous figure, progressive by the standards of his time, but his credentials as a feminist are slightly questionable today, and his vision of reform must be contextualised through a colonialist lens.

Karsandas Mulji

In 1832, the year of Mulji’s birth, Bombay was emerging as a city on the cusp of transformation. It was the year of the Bombay Dog Riots, of the deadly cholera epidemic, and of widespread advancement in commerce, industry and education, such as the advent of literary societies and increased trade. Although he was born in Gujarat, Mulji’s family soon relocated to Bombay, drawn to the vibrant diversity and multitude of opportunities the city offered.

As a young adult, Mulji was among the most prominent members of the class, which Parsi historian Christine Dobbin termed “the Bombay intelligentsia.” A conventional example of a Macaulay man, Mulji was educated at the prestigious Elphinstone College, where he met and befriended other prominent reformers such as Dadabhai Naoroji, who was also known as the ‘Unofficial Ambassador of India’; Bhau Daji, the antiquarian Sheriff of Bombay; Justice MG Rande, social reformer and one of the founding members of the Indian National Congress; and the Gujarati poet Narmadashankar Dave.

In Spiritual Despots (2016), Canadian historian JB Scott writes that after these men graduated from Elphinstone and entered into public life, they formed a “new elite” that eventually wrestled power and influence away from their traditionalist competitors.

Dadabhai Naoroji was a friend of Mulji’s from Elphinstone College (Wikimedia Commons)

Dadabhai Naoroji was a friend of Mulji’s from Elphinstone College (Wikimedia Commons)

In 1851, Mulji began his first stint as a journalist, contributing to the now defunct Rast Goftat the same year. Mulji invited criticism from the onset, penning controversial articles advocating for widow remarriage.

When news of the same reached his aunt, who had cared for him since his mother’s death, she immediately evicted him from her home, leading the young reformer to fend for himself. Undeterred, Mulji continued to contribute to Rast Goftar and, in 1855, founded a Gujarati weekly Satya Prakash. In its first issue, Mulji proclaimed that the paper represented a deadly weapon, a literary embodiment of reformist values that would confront outdated traditions and prioritise knowledge over profit.

By 1857, Mulji was famous within Bombay reform circles. He was well known for his advocacy for widow remarriage and his ardent belief in the value of overseas travel. While these alone invited the ire of his religious compatriots, Mulji doused fuel into the fire when he criticised the leaders of the influential Vaishnavite sect. A Vaishnav himself, Mulji began to expose the misdeeds of the revered Vaishnav Maharajas.

He first wielded his pen against the Maharajas in 1857, when he participated in an essay competition on Gurus and their female devotees. That led to a series of events that eventually required Jivanji, the influential Maharaja of Bombay, to appear in court. In response, the Maharaja closed all Vaishnava temples in the city, and his followers issued a bond stating that no Vaishnav could summon a Maharaja before a court, and were they to do so, they would be excommunicated from the community. Their efforts were temporarily successful, but due to Mulji’s continuing advocacy and the negative attention it commanded, many Maharajas, including Jivanji, fled from Bombay.

In 1860, Jadunath Brijratan, an intelligent and eloquent priest, travelled to Bombay to fill the void left by Jivanji and restore the sect’s influence. He publicly contradicted many of Mulji’s claims and participated in an inconclusive debate on widow remarriage with Narmadashankar. Like his predecessor, Jadunath was staunchly criticised by reformers, culminating in the Maharashtra Libel Case of 1862.

The famous case of 1862

On 21 September 1861, Mulji published an article in Satya Prakash accusing Vaishnavi Maharajas of immorality, writing that “no other sects have ever perpetuated such shamelessness, subtilty, immodesty, rascality, and deceit as have the sect of the Maharajas.” He accused Jadunath of adultery, alluding to reports stating that the Maharaj demanded ‘services’ from the wives and daughters of his followers.

Enraged, the Maharaja filed a libel case against Mulji, suing him and the Satya Prakash publisher for Rs 50,000. Described as the “greatest trial in modern times,” the ensuing spectacle has been extensively documented in the Report of the Maharaj Libel Case and of the Bhatia Conspiracy Case Connected With It (1862), henceforth referred to as MLC.

Before the trial began, Jadunath convened a meeting of the Bombay Bhatia community and decreed that anyone who testified against him would be excommunicated. Upon hearing this, Mulji accused nine Bhatia leaders of conspiracy. Despite a robust defence, several Bhatias testified that they were in fact sworn to silence, with one, Luckmiduss Khimjee, stating that he was given to understand that if he gave evidence, he would be expelled from the caste and his children would be barred from marriage.

After nine days of proceedings, the court ruled against the Bhatias, imposing a fine between Rs 500 and Rs 1000 on nine members of the sect. According to the MLC, “The eyes of India were riveted on the proceedings. The disclosures in court startled the outside world. They were revelations of a theology the most hateful, amorality the most outrageous and filthy, a body of religious guides who may be described as living incarnations of Satan.”

Soon after, the libel case against Mulji was heard by the Bombay High Court, with Chief Justice Mathew Richard Sausse presiding. The Justice acknowledged that the validity of the case was tarnished from the onset due to the events of the Bhatia conspiracy.

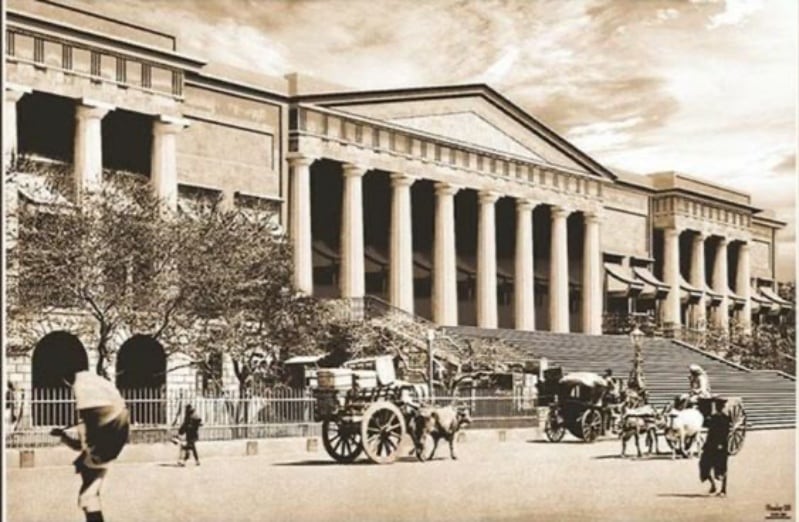

Bombay High Court in 1830, now the Asiatic Society (Archives)

Bombay High Court in 1830, now the Asiatic Society (Archives)

What followed reads like a crime thriller: a fierce battle between Jadunath (the plaintiff) and Mulji (the defendant) set against the backdrop of Bombay’s Town Hall, emblematic for its grand columns and sweeping steps. Mulji’s lawyer, Thomas Anstey, began by arguing that no individual can be prosecuted for heresy (religious defamation) in a temporal court unless such an offence was previously mandated to be punishable by law. Lyttleton Bayley, for the plaintiff, said that Jadunath was targeted as a private individual, not a spiritual leader, and if the court allowed that to proceed, every Brahmin in the land could be “libelled with impunity.”

Both sides then fiercely debated Hindu theology, with Anstey arguing not against religious beliefs but against the Vaishnavas’ interpretation of them. The court eventually stated that Mulji’s statements would not be considered libellous if he could prove that Jadunath had offended public morality. To make this case, the defence brought in several witnesses who claimed that Jadunath was “addicted to the society of women.” One said that as a teenager, he was asked to pay a fee to watch the Maharaja have sex with another man’s bride. He spoke of it plainly and considered it a privilege. Most damningly, two doctors testified to having treated the Maharaja for syphilis.

After 19 days, the Maharaja finally arrived in person, subjecting himself to the judgment of a court that viewed him not as a God or a guru, but as an ordinary subject of the Crown. The Maharaja’s case was already on precarious grounds owing to the Bhatia case, the testimony of Astley’s witnesses, and the fact that witnesses for the plaintiff were all members of his sect. Jadunath made matters worse by initially refusing to swear on the Holy Book, expressing his unfounded fear that someone would touch him, and answering questions with meandering theology.

On April 22, 1862, Judge Joseph Arnould issued the verdict of the court in favour of the defence. In a scathing criticism of the Maharaj along with the caste system as a whole, he said, “It is not a question of theology that has been before us. It is a question of morality. The principle for which the defendant and his witnesses have been contending is simply this: That what is morally wrong cannot be theologically right.”

The case captured the attention of India and the world. It was described by the MLC as an instance in which “human nature rises in rebellion against the morality of a theology which sanctions and imperatively enjoins adultery.” However, two major consequences of the case — its cultural implications and its effect on women — remain relatively unexplored.

Cultural change

To understand the cultural context behind the case, it is important to look back at the year 1835, when Thomas Babington Macaulay delivered a treatise on Indian education. Macaulay believed in the need to civilise the native population through western education, transforming the elite from subjects to intermediaries of the Crown. In the wake of Macauley’s speech, the East India Company began investing huge sums of money into educational institutions, including the likes of Elphinstone College. This had a profound effect on the students, with Narmadashankar writing that “as we studied Western history, we began to visualise a way of life similar to that of the Westerners.”

Mulji himself was a keen admirer of Western civilisation. After travelling to England in 1863, he wrote gushingly about the beauty, splendour and civility of the country, stating that Indians should not judge the English by their behaviour in India, which he believed was simply a tactic to broaden the mind and educational prospects of the public. In Can the Hypnotized Subaltern Speak (2020), Dhwani Vaishnav, Assistant Professor at the Shantilal Shah Engineering College in Gujarat, writes that for Mulji, “travel seems to have reinforced his notion that colonialism was not merely justifiable but it was fortunate.”

That however, came much after the trail, but even in 1862, Mulji’s knowledge of Western culture proved to be an advantage.

In Creating a Community of Grace (2004), Athabasca University professor Shandip Saha writes that Mulji, “being a member of an English-educated elite of urban leadership in the Presidency,” knew how to “manipulate” the English legal system. As soon as Jadunath sued Mulji, Saha states, “he surrendered his power and authority to representatives of the colonial justice system, which did not care for his standing as a maharaja.”

Indeed, Mulji did seem to have a better grasp of how to appeal to the court, relying on prominent, educated eyewitnesses to give his case credibility. The English judges also demonstrated an orientalist misunderstanding of Hindu customs. As David Haberman, professor of religious studies at Indiana University, states, the trial hinged on the “ontological hierarchy” of guru and disciple. While Vaishnavis believed that the Maharaja was an incarnation of Krishna and therefore inherently different from his followers, the court saw the plaintiff, defendant, and witnesses as materially identical subjects of the Crown. The translation from vernacular languages to English compounded the problem.

One instance stands out in particular.

Asked by Anstley if some Vaishnavas believe the Maharaja to be a God, a witness for the plaintiff replies, “we consider him to be our gooroo.” Confused, Anstley asks again, “is a Gooroo a God?” The witness reiterates (earning himself a court fine in the process), “a Gooroo is a Gooroo.” The English judges considered this answer to be insufficient, believing it to be a tactic of diversion. However, for the witness himself, it is likely that his statement stood for itself – a Guru is a Guru; no further analysis required.

The trial largely “evacuated traditional institutions,” according to Scott, “so that caste would retain its salience only as a social marker.” As with the abolishment of Sati in 1829, preventing religious leaders from sexual impropriety may now seem progressive and self-evident, but at the time, for some, it represented a colonial ignorance of local customs rooted in the perceived moral superiority of the English. The trial “testifies to the emergence of an Orientalist legal apparatus that displaced traditional structures of religious authority in the process of asserting its own ability to adjudicate Hindu orthodoxy,” writes Scott.

Simply put, the English believed that they were culturally superior to the natives, an idea that anglophiles like Mulji, largely subscribed to. As Scott writes, Mulji’s reform agenda was “not simply about liberating liberal subjects but rather about producing them.”

Another point of contention relates to the characterisation of women by Mulji and his supporters.

Despite the fact that the case concerned the exploitation of women, no women were invited to participate. Even Streebodh, a journal co-founded by Karsandas, in 1857, failed to mention the case while proceedings were ongoing. In Puppets on the Periphery (1997), author and politician Usha Thakkar writes that the decision to limit the participation of women in the court and the press, “is to limit the sphere of women to home and family, and not involve them in the larger issues outside.”

As Mulji himself wrote, “the Maharajas are offered the wives and daughters before they are put to their own use.” Implicit in his statement is the role of a woman. They are docile creatures, free from blame for engaging in adultery, but also devoid of the agency to refuse.

In Women in the Maharaj Libel Case (1997), SOAS professor Amrita Shodan writes that the “only women whose activity was recognised by the reformers as independent were the older single women, mostly widows. Even in the article that sparked the case, Mulji charged the Maharaj with “spoiling” women, indicating, according to Shodan, that “the reformers were provoked more by the promiscuity of the Maharajas with other men’s wives and daughters, rather than by the criminal offence of forcing unwanted sexual attention on women and girls.”

The solution prescribed by Satya Prakash, then merged with the Rast Goftar, was to eradicate women from public spaces. In an article written in 1861, Mulji stated that women should be prevented from going to the temple and from visiting Maharajas without supervision. “Claim them as your own only,” he said. Thus, Shoden argues, though in other places, Mulji may have advocated for women’s rights, with regard to religious reform, the “solutions were restrictive rather than emancipatory.”

In his judgment, Justice Arnould praised the reformers for boldly proclaiming to the votaries of religion, that “their Evil is nor Good,” and “their Lie is not the Truth.” They did so bravely, he said, and all must “express a hope that what they have done will not be in vain.” Despite the contemporary context in which their shortcomings may be evaluated, the enduring legacy of men like Karsandas Mulji is a testament to the fact that their efforts will indeed not be forgotten.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05