Govajang is a village located in the border town of Moreh in Manipur. As per the 2011 Census, the village comprises 35 households with 123 inhabitants. The primary source of livelihood here is rice cultivation. As part of the India-Burma border fencing project (approved in 2010), the Centre erected a border pass through Govajang village. By 2014, about 3.47 km of border fencing was completed, dividing the village between India and Myanmar. In India and Myanmar Borderlands: Ethnicity, Security, and Connectivity (2020), author Pahi Saikia et al writes: “Village residents expressed how the erection of border fences would disrupt the socioeconomic ties and the circulation of cultural relations among the Kukis living on the other side of the border in Myanmar”.

“The India–Myanmar frontier has historically remained porous and lightly guarded; while hardly 10 km of it was fenced earlier, by 2024 the coverage had increased to around 30 km. The porous nature is not accidental— it reflects the social fabric of the borderlands,” says Sreeparna Banerjee, Associate Fellow, Observer Research Foundation.

Unlike the Indo-Bangladesh border, where porosity largely stems from topography, the porosity in the India-Myanmar border stems from the deep-rooted cultural and linguistic bonds. Banerjee explains in an interview with Indianexpress.com that the people inhabiting this stretch, the Nagas, Kukis, Mizos, and Chins, straddle both sides of the border, maintaining kinship ties, cultural practices and economic exchanges that long predate the imposition of an international border.

Spanning 1,643 km, the India-Myanmar land boundary passes through the northeastern states of Arunachal (520 km), Nagaland (215 km), Manipur (398 km), and Mizoram (510 km). The border is marked not only by its rugged terrain but also by its deep cultural ties – ties that have been tested by the drawing and redrawing of borders.

The Anglo-Burmese rivalry

Since the late 19th century, Myanmar (then Burma) had been flourishing, attracting Bengali, Armenian, Tamil, Chinese, and Japanese merchants. There was also an influx of migrant workers, with the “Burmese Dream rapidly outpacing the American one,” notes Sam Dalrymple in his book Shattered Lands: Five Partitions And The Making of Modern Asia (2025).

By the 18th century, Britain had established supremacy in India. In the following century, it aspired to extend its rule to Burma, drawn by its natural resources. There was also the pressing desire to open a trade route to China through Burma.

By the end of the 18th century, however, a combination of factors fuelled the conflict between British India and Burma. In January 1824, Burmese troops attacked Eastern India, particularly Cachar, which was a British-protected state. This led to the First Anglo-Burmese War in March 1824. The war ended with the Treaty of Yandabo in 1826, whereby Burma yielded her suzerainty over Manipur and Assam, ceding the provinces of Arakan and Tenasserim, paying indemnity, and permitting the exchange of envoys with the British.

Story continues below this ad

Rangoon (Yangon) in the 1890s (Wikimedia Commons)

Rangoon (Yangon) in the 1890s (Wikimedia Commons)

“The kingdom of Burma was down, but not out yet,” cautions former Ambassador Rajiv Bhatia in India-Myanmar Relations: Changing contours (2016). The Second Anglo-Burmese War followed (1852-53), resulting in the fall of Lower Burma. “In December 1852, [Governor-General Lord Dalhousie] proclaimed the annexation of the province of Pegu. The three Burmese provinces (i.e. Arakan, Tenasserim, and Pegu) were ruled by Company officials separately until 1862, when, at the end of the Company Raj, they became a single province of British India to be ruled by a Chief Commissioner,” writes Bhatia.

The Third Anglo-Burmese War (1885-87) led to the annexation of Upper Burma. “The idea and plan to subjugate Burma, divesting it of its independence and monarchy, which was absolutely pivotal to its socio-political structure, was that of Britain,” notes Bhatia.

Banerjee adds, “The origins of the India-Burma border can be traced back to the colonial period when British expansion into Burmese kingdom during the 19th century gradually reshaped the political geography of the region”.

Separation of Burma & India

The Simon Commission arrived in Burma on January 29, 1929, with the purpose of assessing whether the region should be separated from India and made a distinct colony. “Indeed, at the time,” notes Dalrymple in his book, “there was a huge amount of opposition to even separating Burma at all. Many Burmese worried that separation would eviscerate their thriving economy…” he writes. But the Commission had made up its mind even before reaching Rangoon that Burma was not part of India.

Story continues below this ad

The Commission concluded that Burma and India were two completely different countries. Bhatia writes, “It favoured immediate separation…but it did not make any recommendation on what kind of constitutional order should be given to a Burma separated from India”.

Photograph of surrender of the Burmese Army, 3rd Anglo-Burmese War (Wikipedia)

Photograph of surrender of the Burmese Army, 3rd Anglo-Burmese War (Wikipedia)

Interestingly, Mahatma Gandhi also visited Rangoon in March the same year. While his speeches attracted a large crowd of people, his vision left the masses feeling dejected. Gandhi declared that Burma was not part of Bharatvarsha – later expanding, as Dalrymple cites, “it would only be worth the while of Burma to remain part of India if it means a partnership at will on a basis of equality with full freedom of either party to secede whenever it should wish”.

At the Burma Roundtable Conference, held between November 1931 and January 1932, London announced its decision to have the separation issue decided through a general election in Burma. “Separation would mean a new constitution, whereas continuation with India would mean permanent stay (short of the Dominion status) within the proposed federation. Elections on this all-important issue took place in November 1932. The verdict was decisively and clearly against separation,” notes Bhatia, adding, “Regardless of the electoral verdict, subsequent political developments took Burma inexorably towards separation”.

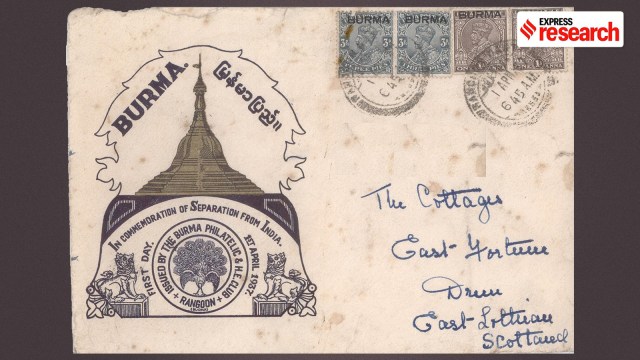

The British parliament considered the Government of Burma Bill in 1934–35, and the Act that separated Burma from India came into effect on April 1, 1937. Burma was made an entity of its own within the British Empire, to be governed under the supervision of the British government in London. “The shattering of the Indian Empire began in 1937, when the first largely forgotten partition carved Burma out of India to fulfil a decades-old demand by the ethic Barmar community, as well as the desire of Hindu nationalists for ‘India’ to match the boundaries of the ancient Hindu holy land of ‘Bharat,’” writes Dalrymple.

Story continues below this ad

Between 1937 and 1942, Burma functioned as a separate colony under the Raj. From 1942 to 1945, it was ‘liberated’ but remained under tight Japanese control. British authority was restored from 1945 to 1947, following the end of World War II. “The Raj lasted 61 years, counting from 1886 to 1947, as Burma gained independence in January 1948,” writes Bhatia.

In India and Myanmar Borderlands (2020), Ngamjahao Kipgen writes: “The separation of British India and Burma in 1937 and the Partition of India in 1947 created arbitrary boundaries, dividing many ethnic groups such as the Kuki-Chins and placed them into different nation-states.” These borders, he notes, were created by ignorant colonial overlords who ignored geographical and historical realities as well as economic interdependence, resulting in chaos in the borderland.

The drawing of borders

Interestingly, neither the Government of India Act of 1935, which recommended the separation of Burma from India, nor the Indian Independence Act of 1947 gave any attention to the India–Burma boundary. Instead, the matter was left for the postcolonial states to resolve.

On its uniqueness among South Asian borders, Dalrymple opines in an interview with Indianexpress.com: “I mean for one, until recently, it has not been walled, which I think is odd. India’s borders are some of the most fortified borders in the world. The India-Pakistan border, for instance, is visible even from space! In contrast, the border of India and Burma is remarkably uncentral to India’s self-image compared to the other borders that emerged from the Partition”.

Story continues below this ad

The formal agreement on the boundary between India and Burma was signed on March 10, 1967. The Ministry of External Affairs on its website provides the ‘Boundary agreement between the Government of India and the Government of the Union of Burma’ that clearly stated the demarcation of a 1,643-km-long boundary line which runs from the ‘tripoint with China in the north’ to the ‘tripoint with Bangladesh in the south.’ This boundary follows the ‘traditional’ line between the two states, i.e. India and Burma. “By ‘traditional’ line”, explains academic Pum Khan Pau in The Partition of the Indian Subcontinent (1947) And Beyond: Uneasy Borders (2023), “it means the administrative borders drawn by the colonial state in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, respectively”.

Pau cautions, “…the boundary treaty between India and Burma in 1967 was only a formality of affirming what the colonial state had already delineated”.

Living at the border

Among the many villages that dot the India-Myanmar border is Hmaungbuchhuah in Lawngtlai district of Mizoram. It displays patterns of lifestyle which, scholar Rajeev Bhattacharyya notes in India and Myanmar Borderlands (2020), “are similar and dissimilar to other settlements.” Many settlements on the borderlands lack educational infrastructure and medical facilities, and Hmaungbuchhuah is no exception.

During his field visit to Hmaungbuchhuah some years ago, Bhattacharyya found an abandoned school in the district. “There are no teachers who know the Zakai language, nor any books or syllabus designed specifically for the community. There are no schools across the border where the children could have enrolled themselves. The few monks stationed at the monastery in the village sometimes gather the children around them for informal classes but they are irregular and inconsistent,” he notes. Families with capital have begun to send their children for studies to Arunachal Pradesh.

Story continues below this ad

There is also a very high incidence of diseases like malaria and jaundice at Hmaungbuchhuah, besides the other ailments. Bhattacharyya writes, “Every year, these diseases take a toll in the absence of either health centres or hospitals in close proximity. The civil hospital is located at the headquarters in Lawngtlai but availing its services could depend upon availability of transport.” There was a case, he cited, where a patient breathed his last as he needed a surgery but there was no surgeon in the hospital.

In terms of preventive measures, Bhattacharyya found, some pills imported from Myanmar are kept handy. In the absence of electricity, firewood is the fuel for all the households, which also becomes scarce during the rains. He adds, “Electric poles were erected early in 2018 but there was no supply of power.” A Google search of the village today yields little more than a weather forecast and a few connectivity options; it remains as distant from mainstream news as it does from the internet.

Transit & transgression

Unlike the rigid bordering practices along the borders between India and Pakistan, the India–Myanmar borders are marked by limited border norms like walls and border fencing. They are, instead, characterised by porosity and special arrangements for the transit of people under the Free Movement Regime (FMR).

Banerjee explains in her interview, “After independence, the government of India recognized that the India-Myanmar borderland was home to tribes who shared deep cultural, social, and economic bonds that predated the international boundary. For them, crossing the border was an integral part of their daily lives, tied to subsistence practices and family networks. To prevent disruption of this way of life, New Delhi introduced special provisions to allow hill tribes to move across the frontier without travel documents.”

Story continues below this ad

“On September 26, 1950, the Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) issued a notification amending The Passport (Entry Into India) Rules. So this exempted hill tribes who are either citizens of India or the Union of Burma and ordinarily resident within 40 kilometers on either side of the frontier from carrying passports or visa when they are entering India,” Banerjee adds.

However, the FMR was soon exploited by insurgent groups in Northeast India. “Insurgents took advantage of the porosity of the frontier using it to slip into Myanmar for training, safe havens and supplies before re-entering India to carry out attacks,” says Banerjee. In August 1968, thus, the MHA introduced a permit system, whereby both Indian and Burmese citizens had to obtain prior authorisation from their respective governments before crossing the border.

Rickhawdar (Myanmar, left)- Zokhawthar (India, right) border crossing. (Wikimedia Commons)

Rickhawdar (Myanmar, left)- Zokhawthar (India, right) border crossing. (Wikimedia Commons)

In 2004, India reduced the permissible movement under the regime to 16 km on either side of the border and limited crossing to three designated points. “One was in Arunachal Pradesh, one was in Manipur, and the other was in Mizoram,” she says. This system was eventually formalised through the signing of the India–Myanmar Agreement on Land Border Crossing in 2018.

Scholar Pratnashree Basu, in her chapter in India and Myanmar Borderlands, argues: “While [FMR] is susceptible to being misused by militants and smugglers who gain easy access to either side of the border, at the same time, it is extremely beneficial to people who inhabit these areas and share similar cultural histories, especially the Naga, Meitei and Kuki tribes”. The border town of Zokhawtar, located in Mizoram, she cites as an instance, consists of only a bridge dividing two parts of what is actually one large settlement. Since there are English medium schools on the Indian side of the town, children from across the border are enrolled in these schools and cross the bridge every day to come and attend classes on the Indian side. “The FMR has made this possible.”

Story continues below this ad

Yet, the fear of fencing clouds the minds of those on the borderland. Banerjee argues, “The lens with which India is looking into the current India-Myanmar border dynamics, and especially after the coup that took place in 2021, is very volatile in nature. Discussions in 2024 entailed scrapping the FMR completely and fencing the border”.

She adds that from December 2024, the permissible limit for movement has come down to 10 km from 16 km. “Tightened border pass requirements have started being laid out, where there will be biometric channels of verification of one’s identity, signalling a move away from community-based trust arrangements toward a heavily regulated pass-based system that was not there before,” she sighs.

Dalrymple remarks, “I think that the government should worry about cutting people off and trying to divide people with arbitrary fences. This is precisely what led to so many of these secessionist movements in the past. And it’s only through understanding that, that we can attempt to heal these borders and allow these regions to economically thrive”.

While the border was drawn and redrawn several times to suit political objectives, the collateral damage done to the ethnic communities in whose territory the border was drawn largely remains unnoticed.

Rangoon (Yangon) in the 1890s (Wikimedia Commons)

Rangoon (Yangon) in the 1890s (Wikimedia Commons) Photograph of surrender of the Burmese Army, 3rd Anglo-Burmese War (Wikipedia)

Photograph of surrender of the Burmese Army, 3rd Anglo-Burmese War (Wikipedia) Rickhawdar (Myanmar, left)- Zokhawthar (India, right) border crossing. (Wikimedia Commons)

Rickhawdar (Myanmar, left)- Zokhawthar (India, right) border crossing. (Wikimedia Commons)