Who gets to govern Delhi and how much of it? This has been a question haunting much of the city’s history since it became the British capital in 1911.

The Sepoy Mutiny of 1857 was in many ways a milestone moment in the history of British rule in India. Most importantly though what it did was to jolt the British into realising the problems of governing over a subcontinent as large as India from its Eastern corner. Rumblings over the need to shift the capital from Calcutta had been going on for more than a century before the Mutiny. Warren Hastings, the governor-general of Bengal between 1773 and 1785, had written a memo as early as 1752 citing the defects in Calcutta in serving as the seat of British Rule in India.

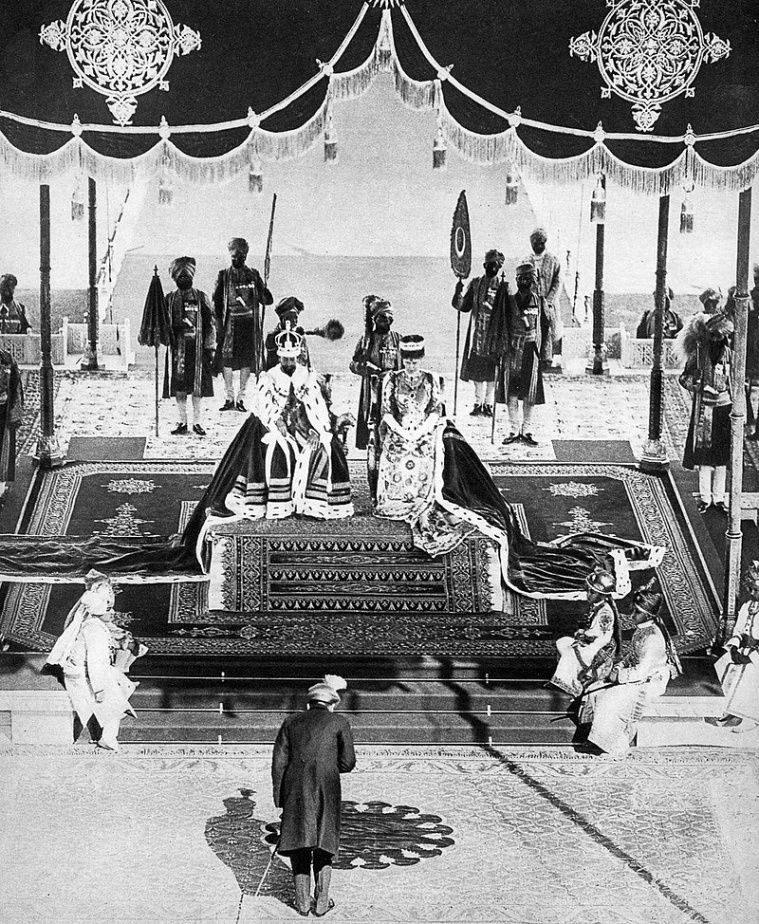

A post-Mutiny committee headed by Sir Stafford Northcote, the Secretary of State for India, favoured the decision to shift the capital along with giving full governorship to Bengal. Discussions were revived in 1877 by the then Viceroy, Lord Lytton, and yet again during the Durbar of 1903. However, it was the nationalist movement that swept through Bengal, especially after Curzon decided to partition the province, that proved to be the immediate catalyst. Finally, the historic decision to shift the capital happened during the Durbar of 1911.

Delhi was chosen as the new capital for several reasons. Suoro D Joardar, professor in the Schoor of Planning and Architecture in New Delhi in his article New Delhi: Imperial Capital to Capital of World’s Largest Democracy (2006) notes that besides the centrality and connectivity of Delhi, it also “carried in the minds of the colonial rulers a symbolic value- as the old saying goes: ‘he who rules Delhi rules India’- a realisation of the Indian ethos, especially across northern and central India, enhanced during royal contact with the innumerable minor and major princes.” Further, the British also hoped to gratify the Muslims by moving to a site that had historically been the centre of Pathan and Mughal dynasties.

Though the seat of Mughal power in the past, Delhi in the years after 1857 was no more than a humble provincial town, stripped of the memories of its glorious past. It had been gifted to the state of Punjab by the British for their loyalty during the revolt. A rarely remembered nugget of Delhi’s history is the fact that the first three colleges of Delhi University — St. Stephens (established in 1881), Hindu (established in 1899), and Ramjas (established in 1917) — were part of the Punjab University in Lahore until the capital was shifted and it was felt necessary to have a large educational institution in the new capital of India.

When the call for the shifting of the capital came in December 1911, the administration of Punjab and the imperial government had to make several negotiations regarding the responsibilities of improving and developing Delhi in a manner fit to be the capital. Delhi had to be brought back upon the political map of India and the Municipal Committee of Delhi was faced with a mammoth task of using a provincial city’s funds and machinery to build an imperial capital.

Malcolm Hailey, who later became the governor of Punjab, is known to have congratulated the Delhi Municipality for “making much progress in facing the problem of adapting the machinery and methods of a provincial town to the complex needs of the capital of India”, writes historian Narayani Gupta in her book Delhi between two Empires (1803-1931) (1998).

But soon afterwards the case was made that the municipality cannot be expected to be financing and administering the making of a capital city. “You cannot expect the city to bear all the expenses of the improved administration….for the demand is not the demand of the people but of the government,” said Hailey’s aide Sir Geoffrey de Montmorency, while making a case for more financial aid to be given from the government to the municipality.

Who and how must Delhi be administered was yet another question that cropped up with much urgency. The Cantonment Code was considered for a brief while. Gupta in her book notes that this would mean a government consisting of the chief commissioner and various officials including some of the best members of the Municipal Committee who could be nominated. The governor of Punjab, Louis Dane, however, was of the opinion that the provincial government of Punjab could carry out the governance as effectively as the imperial government and that less disruption would be caused if Delhi was retained in Punjab.

The Cantonment Act was not extended to Delhi, but the degree of effective self-government was considerably reduced. The chief commissioner was to play a significant role in the administration of the city because it was not an imperial enclave. Further, the area under the Municipality’s authority was cut down quite drastically. The Civil Lines along with 500 acres to its north was turned into a Notified Area Committee. From 1912 to 1922, when New Delhi was being built, it was maintained as a temporary capital to house representatives of the imperial government. A Viceregal lodge was built north of the Ridge in which the Viceroy was to stay. Later, it came to be used as the office of Delhi University. A Secretariat was also established on Alipur Road and also a makeshift office for the commander-in-chief came up south of Alipur Road. The latter was meant to be demolished in 1930 but was sold to Indraprastha College in 1932.

Story continues below this ad

The Notified Area was initially brought under a tripartite administration consisting of the municipality, the cantonment, and the temporary works directorate. However, the arrangement was considered ineffective soon afterwards and gave way to a Notified Area Committee. As Gupta writes, “it was a simplified form of municipality”. The committee had only five members: the president, the military chief, the civil surgeon, a representative of the Punjab Chamber of Commerce, and one Indian member.

Even in these early days of the capital building, the tussle between the municipality and the imperial government had become evident. “Both the municipality and the notified area received imperial grants. Not only did the notified area get the lion’s share, but it also exploited the municipality,” Gupta writes.

Once New Delhi as the capital had taken shape, the imperial government, through the Government of India Act of 1919 and 1935, classified Delhi as a chief commissioner’s province, which is equivalent to a Union Territory today. Delhi was broken away from the Punjab province and was to be administered by the Viceroy of India, acting through a chief commissioner.

The capital of independent India

The power tussle and debate over the administration of Delhi have been ongoing since the making of independent India. Every political party, both at the Centre and in Delhi, has at various points in time argued for and against the idea of full statehood. At present, the authority over Delhi is shared between the Legislative Assembly and the Centre.

Story continues below this ad

As early as July 1947, the Pattabhi Sittaramayya Committee had advised for greater autonomy in Delhi’s governance. The committee had been set up to study the administrative structures in the chief commissioner’s territories. It singled out Delhi as a special case to be planned and developed as a national capital. Having taken into consideration the circumstances under which Delhi was made an imperial capital by the British, the committee concluded that the “province which contains the metropolis of India should not be deprived of the right of self-government enjoyed by the rest of their countrymen living in the smallest of villages.” Consequently, it recommended Delhi be governed by a lieutenant governor appointed by the President of India along with an elected legislature.

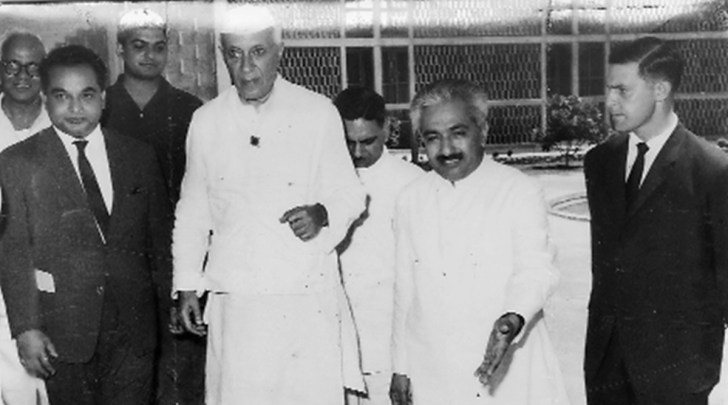

However, the recommendations were opposed by the Drafting Committee of the Constitution headed by B R Ambedkar. Jawaharlal Nehru who was part of the committee also had strong reservations against having a local government functioning in Delhi. He sympathised with the people of Delhi but argued that “Delhi is not a static situation.”

Jawaharlal Nehru addressing the Constituent Assembly (Express Archives)

Jawaharlal Nehru addressing the Constituent Assembly (Express Archives)

The Drafting Committee’s views on Delhi were not without its criticism. The strongest opposition came from the representative of Delhi, Deshbandhu Gupta. In what was a major showdown with Ambedkar, Deshbandhu noted, “I ask my worthy friend that while he poses to be the standard-bearer of the minority-rights—Dr. Ambedkar’s attentive eye at once catches even the minutest point, if any, concerning the minorities—how did the claim of this small province escape his notice? He should have shown some consideration to Delhi, regarding it at least as a minorities’ province.” [as cited by Niranjan Sahoo in his article Statehood for Delhi: Chasing a Chimera (2018)]

However, the Drafting Committee went ahead with its plans and forfeited its right to have a Legislative Assembly. It was to be governed exclusively by the president through a lieutenant governor appointed by him.

Story continues below this ad

But in 1951, the status of Delhi was changed when the Government of Part C States Act allowed for a Legislative Assembly to be formed in the city. Subjects such as public order, police, land, and municipality were left with the central government. Consequently, in 1952, Delhi had its first chief minister — Chaudhary Brahm Prakash of the Indian National Congress.

Prakash, however, resigned from his post in 1955 after a prolonged standoff with chief commissioner Anand Dattaya Pandit and later with the then Union home minister Govind Ballabh Pant over matters of jurisdiction and functional autonomy.

The classic case is that of the first Assembly that was constituted in 1952 with Chaudhary Brahm Perkash as the first chief minister. It was a clash that ended with Perkash’s resignation, followed soon after by the abolition of the Delhi Assembly. (Expres Photo)

The classic case is that of the first Assembly that was constituted in 1952 with Chaudhary Brahm Perkash as the first chief minister. It was a clash that ended with Perkash’s resignation, followed soon after by the abolition of the Delhi Assembly. (Expres Photo)

Meanwhile, the States Reorganisation Committee was set up in 1953 with the task of reorganising the states’ borders for better governance in an independent India. Sahoo in his article writes that perhaps the committee’s observations on Delhi were shaped partly by the ongoing feud between Prakash and the chief commissioner and home minister. For it suggested that “the dual control over the national capital had led to marked deterioration of administrative standards.” Consequently, it once again removed the Legislative Assembly from Delhi and suggested the formation of an autonomous Municipal Corporation instead.

The suggestions of the States Reorganisation Committee came under massive criticism both from political figures and from the people of Delhi. Sahoo cites the concerns raised by Member of Parliament, Sucheta Kriplani, who said, “Delhi is going to lose its democratic set up. We are going to lose the status of State. Our people will be disenfranchised. In place of the legislature we are going to be given a corporation with limited powers. Therefore, I feel Delhi is not being dealt with fairly.”

Story continues below this ad

Ignoring the voices of opposition though, the Union government enacted the Delhi Municipal Corporation Act in 1957, which provided for a Municipal Corporation to be elected in Delhi through universal adult franchise which would have jurisdiction over the entire city.

The dissatisfaction over the status of Delhi did not die down for the next several decades. In the 1960s, the Municipal Corporation was replaced by the Metropolitan Council to ensure greater representation of the people through 56 elected and five nominated members.

With the Jana Sangh emerging as a strong political opponent of Congress in the 1970s, the issue was further politicised. In 1977, for instance, the Jana Sangh which was heading the Metropolitan Council moved a resolution demanding that “Delhi be given the status of a state” to ensure its all-round development. The Congress while heading the fourth Metropolitan Council had moved four proposals demanding statehood for Delhi.

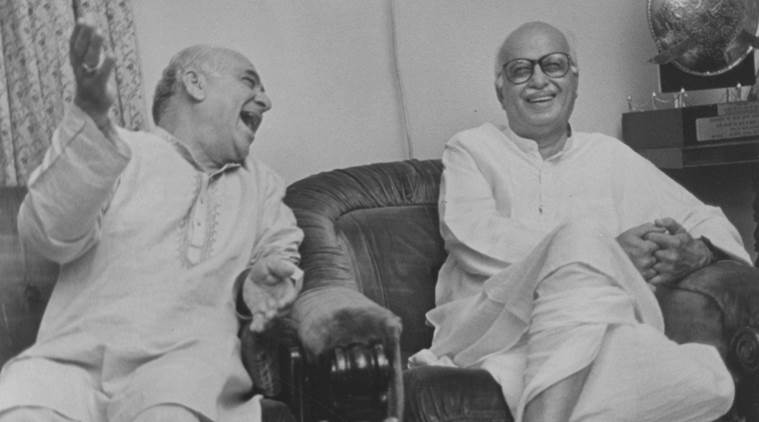

Sahoo notes that by the late 1980s, the demand for statehood in Delhi was gaining unprecedented traction with members of the Opposition raising their concerns about a Legislative Assembly in the Parliament almost every day. The most vocal among them was the representative of the BJP (descendant of the Jana Sangh), Madan Lal Khurana. So fierce was Khurana’s political rallying around statehood that it earned him the epithet, ‘Dilli ka sher’ (lion of Delhi).

Story continues below this ad

Finally, in 1987, the Centre agreed to set up a committee to review the administrative set-up in Delhi. The Sarkaria Commission, under the chairmanship of Justice R S Sarkaria, after studying the existing structure in Delhi emphasised that while the Centre needed to have substantial control over the administration of the national capital, the people of the city also needed a representative body to look into the matters of their daily life. Thereby, it recommended the reinstatement of a Legislative Assembly in Delhi, which was carried out through the 69th Amendment to the Constitution in 1991. Ironically, the Congress at the Centre, which had in the past demanded statehood for Delhi, suddenly made a political U-turn.

BJP leaders Madanlal Khurana and L K Advani sharing a joke at later’s residence. (Express Archive)

BJP leaders Madanlal Khurana and L K Advani sharing a joke at later’s residence. (Express Archive)

Since 1991, the statehood of Delhi has been an electoral issue. It is as much a political tug-of-war between parties in the state and the Centre as it is a matter of winning votes by pandering to popular concerns over the effective governance of the city.

Yet, as experts would point out, the situation is not unique to the Indian capital. In the American capital Washington DC, for instance, a series of popular movements since the 1990s has emerged demanding full statehood. Similar tensions caused due to overlapping jurisdictions have arisen in the Australian capital Canberra as well as in Brazil’s capital Brasilia. Sahoo points out that “conflicts and misunderstandings are the inevitable facet of the national capital governance system.” However, what Delhi can learn from other countries, he suggests, is putting in place some form of an institutionalised mechanism for better coordination and a healthier form of conflict resolution.

Further reading:

Suoro D. Joardar, ‘New Delhi: Imperial Capital to Capital of the World’s Largest Democracy’ in David Gordon ed. ‘Planning Twentieth Century Capital Cities’, Routledge, 2006

Story continues below this ad

Narayani Gupta, ‘Delhi between Two Empires (1803-1931)’, Oxford University Press, 1998

Niranjan Sahoo, ‘Statehood for Delhi: Chasing a Chimera’ Observer Research Foundation, 2018

The shift of capital from Calcutta to Delhi was announced in the Durbar of 1911. (wikimedia Commons)

The shift of capital from Calcutta to Delhi was announced in the Durbar of 1911. (wikimedia Commons) Jawaharlal Nehru addressing the Constituent Assembly (Express Archives)

Jawaharlal Nehru addressing the Constituent Assembly (Express Archives) The classic case is that of the first Assembly that was constituted in 1952 with Chaudhary Brahm Perkash as the first chief minister. It was a clash that ended with Perkash’s resignation, followed soon after by the abolition of the Delhi Assembly. (Expres Photo)

The classic case is that of the first Assembly that was constituted in 1952 with Chaudhary Brahm Perkash as the first chief minister. It was a clash that ended with Perkash’s resignation, followed soon after by the abolition of the Delhi Assembly. (Expres Photo) BJP leaders Madanlal Khurana and L K Advani sharing a joke at later’s residence. (Express Archive)

BJP leaders Madanlal Khurana and L K Advani sharing a joke at later’s residence. (Express Archive)