In Lahore, the City of Gardens, stands the famous shrine of Madho Lal Hussain. Inside the mausoleum are two graves lying side by side, together in death as in life — the 16th-century Punjabi Sufi saint Shah Hussain and his Hindu companion, Madho Lal.

As the world observes Pride Month, the timeless legend of the Sufi saint who fell in love with a Brahmin boy shows that queer love is not a modern concept, but has existed and been celebrated across the Indian subcontinent for centuries. The dargah where the two saints are interred has been a site of reverence and pilgrimage for devotees across religions. Over the centuries, Mela Chiraghan, which celebrates the Sufi Saint, has found patronage from the Mughals, the British, and even the Sikh emperor Maharaja Ranjit Singh, who famously merged the Urs (death anniversary) of the saint and the festival of Basant.

Draped in red robes, clean shaven, wine flask in one hand and an earthen lamp in the other, the legend of Hussain, the rebellious pir fakir, and his band of disciples dancing through the streets of Lahore in drunken ecstasy continues to capture the imagination over 430 years after his death.

It is said Hussain (1538-1599) faithfully followed Orthodox Islam for 26 years, gaining acclaim, until one day he read the lines: “Harken, Ye Folks, the world is a play and a show, a display of pageantry, pride, and boasting between yourselves, and competing with one another for greater wealth and number of children (Sura Al-Hadid 57: 20).” Interpreting the verse literally, Hussain began to treat the world as just that: an ephemeral playground.

There are varied accounts of how the name of the red-robed Sufi mystic came to be fused with that of Madho Lal, who came from a Brahmin family, and by all accounts was at least 40 years his junior. Legend has it that Madho, a beautiful boy of sixteen, was riding a horse in a market in Lahore when Hussain took one look at him and was besotted, writes Noor Ahmad Chishti, a famed architect and chronicler of Lahore, in Tahqiqat-e-Chishti. In another version of the tale, Hussain came upon Madho in Shahdra, a busy suburb across the Ravi, and fell in love at first sight. It is said that Hussain was so in love with Madho that he began to celebrate the Hindu festivals of Basant Panchami and Holi.

Story continues below this ad

“Once Madho Lal exclaimed that posterity would forget him and only remember the enigmatic poet-saint. So, Shah Hussain assured him that Madho Lal’s name would be taken before his own for all of eternity. And, so it came to be that the saint (Shah Hussain) and his disciple (Madho Lal) are invoked in the same breath,” recounts Zubair Ahmad, a Lahore-based retired English professor and award-winning author of short stories.

This fusing of names to become a single entity embodies the Sufi principle of fana – cultivating a profound love for God so intense that it results in the merging of the individual self with the Divine so that the lover and the Beloved become one. And, there lies the rub, scholars do not agree on whether the relationship between the two was a spiritual bond of a Murshid (spiritual guide) and Murid (the novice seeking enlightenment), or “transgressed” beyond it.

Lore and folklore

In his poems, which remain popular in eastern and western Punjab, Hussain assumes a feminine voice and identifies as Heer, one-half of the star-crossed lovers Heer-Ranjha. One of his verses goes thus: “Ranjhan Ranjhan phiraan dhoudaindi, Ranjhan mairay naal (I wander calling for Ranjhan, but Ranjhan is with me).” Whether Ranjhan refers to the Divine or Madho is open to interpretation. However, the Sufi saints of Punjab that came after Hussain, including Bulle Shah and Waris Shah, continued the tradition of using the trope of Ranjhan as a metaphor for the beloved in their poetry.

As per some accounts, a lovelorn Hussain waited for 16 years for Madho, and would frequently cross the Ravi (the river is a common symbol in all four of the popular tragic romances of Punjab: Heer-Ranjha, Sohni-Mahiwal, Sassi-Pannu and Sahiban-Mirza), and circumambulate the house Madho shared with his wife, a ritual that one could argue borders on the religious. One of his Kafis (a classical form of Sufi music) goes thus: Sajjan bin raatan hoiyan whadiyaan/Ranjha jogi, main jogiani, kamli kar kar sadiyaan (The nights are long without my beloved/ Since Ranjha became a jogi, I have scarcely been my old self; people everywhere call me crazy).

Story continues below this ad

It is said that moved by Hussain’s devotion, a once indifferent Madho eventually became Hussain’s devotee, and the two remained inseparable in life and death.

Renowned Pakistani author Nain Sukh, whose novel Madho Lal Hussain was seen as a “transgressive event in the world of letters in Pakistan,” recounts: “When word got out about Hussain and Madho, a diktat was passed directing that the “lovers” be “caught in the act” and be presented in the durbar. So, a spy followed the saint and his companion to their chambers, but when he opened the door, Hussain and Madho were nowhere to be found, instead two lions were caressing each other.”

In another version, no matter how much the scandalised locals tried, they could not find the door to Madho and Hussain’s chamber.

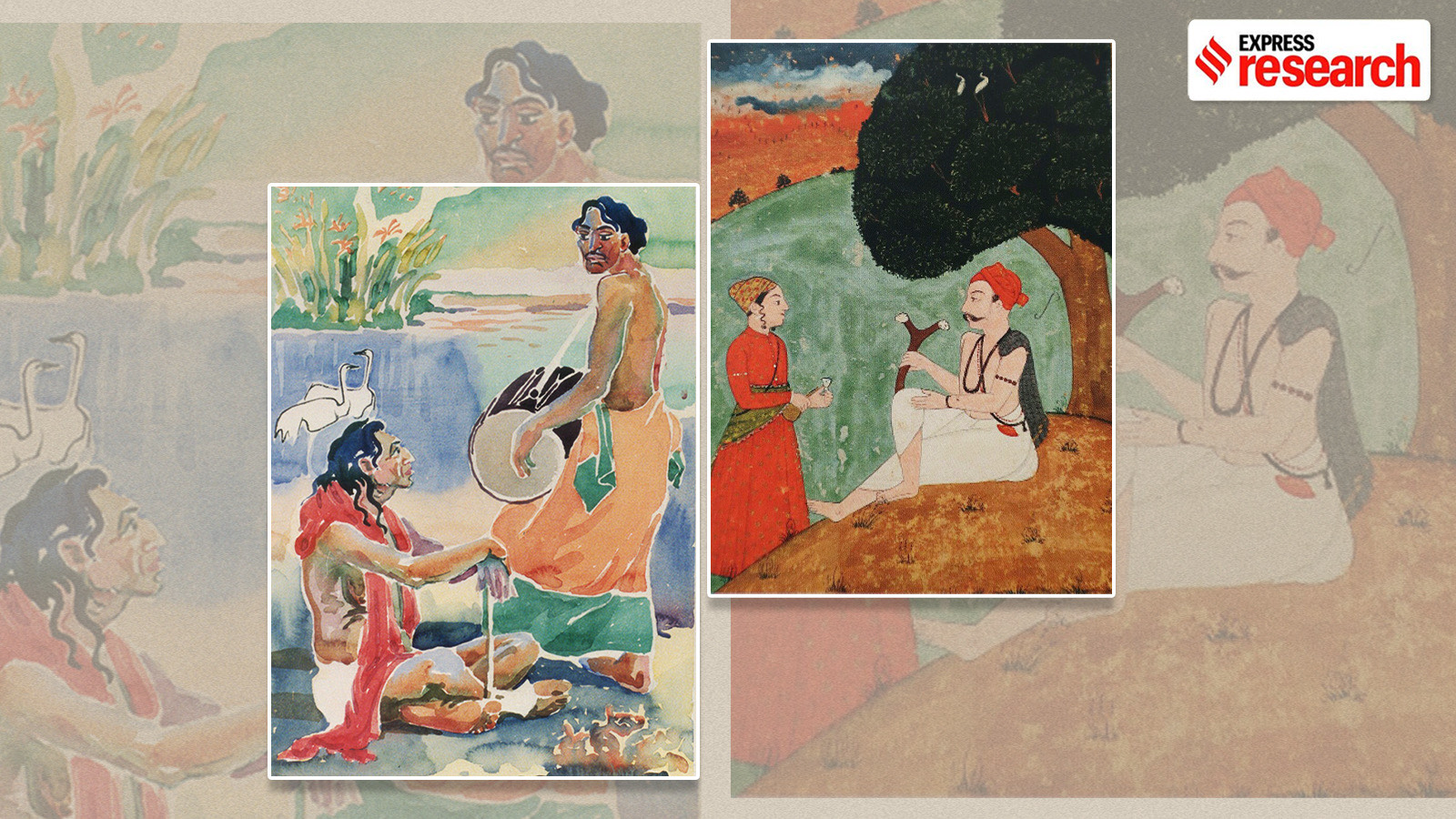

A pictorial depiction of the legend of Madho Lal Hussain and Dulla Bhatti, the Punjabi folk hero who led a revolt against the Mughal emperor Akbar, (right) the chains holding Hussain vanish even as Dulha Bhatti is executed. (Courtesy: Lahore-based painter and political cartoonist Sabir Nazar)

A pictorial depiction of the legend of Madho Lal Hussain and Dulla Bhatti, the Punjabi folk hero who led a revolt against the Mughal emperor Akbar, (right) the chains holding Hussain vanish even as Dulha Bhatti is executed. (Courtesy: Lahore-based painter and political cartoonist Sabir Nazar)

Hussain’s skirmishes with Akbar are the stuff of legends. One relates to Dulha Bhatti of Punjab’s iconic Lohri song “Sundar Mundariye Ho, Tera Kaun Vichara Ho, Dulla Bhatti Wala Ho” fame.

Story continues below this ad

Lahore-based political cartoonist Sabir Nazar, who has depicted the episode in one of his paintings, says, “Hussain was a votary of Rai Abdullah Khan Bhatti, popularly known as Dulla Bhatti, a Muslim zamindar who fought the oppressive tax imposed on peasants and was hanged by Emperor Akbar. It is said that Akbar also wanted to hang Hussain, but no matter how many times the guards shackled Hussain, the chains would vanish. On a metaphorical level, the painting depicts that no matter how much one wants to imprison Hussain’s syncretic poetry, it cannot be chained.”

As per another account, the Mughal guards took the mystic to Akbar who censured him for being publicly intoxicated, but when the wine in his flask was checked, the wine first turned to water, then sherbet, and then milk, tea, vinegar, and then back to wine again.

Unimpressed, Akbar asked his guards to imprison him but was startled to find Hussain in his harem. However, when his prison cell was checked, he was found to be there as well.

It is said Akbar also ordered that all his sayings be recorded in a book, accounts vary as to whether to keep tabs on the unconventional fakir with a large following of devotees or to preserve the saint’s legacy. “However, the secret book, which was called Baharia, has been lost. There is no record of it,” says Ahmad, adding that one set of scholars believe that Hussain was murdered at either the say-so of the emperor or the clergy whose authority he openly challenged through his rebellious poetry.

Story continues below this ad

As per another legend, Hussain had instructed Madho to serve a powerful nobleman for 12 years after his death, he had also told his followers that should they wish to see him again, they would only have to see Madho’s face, and when he returned from service, Madho’s face had turned into Hussain’s, thus becoming Madho Lal Hussain in the flesh.

The shrine where Shah Hussain and Madho Lal are buried at Baghbanpura, near the Shalimar Gardens, in Lahore, Pakistan. (Wikimedia Commons)

The shrine where Shah Hussain and Madho Lal are buried at Baghbanpura, near the Shalimar Gardens, in Lahore, Pakistan. (Wikimedia Commons)

It is said that following Hussain’s death Madho Lal sat in the Sufi saint’s seat for 48 years, secluding himself from the world till he died at the age of 73, after which he was buried right next to Hussain.

A saint of the Malamati tradition

In one of his Kafis, Madho says: “Ve Madho! Main wadda theyaa badnaam! (Madho! I have been slandered).

Some scholars suggest that it was slander and disrepute that the saint set out to court in the first place, and that he encouraged the scandalous rumours, because he followed the Malamati tradition of opprobrium seeking. Practitioners of this tradition go out of their way to become disreputable to eschew the hubris that accompanies fame and acclaim and serves as a barrier between them and the Divine.

Story continues below this ad

Naved Alam, who has penned the Verses of a Lowly Fakir: Madho Lal Hussein, calls the poet-saint “the Donysius of Punjab”. He observes that Hussain’s self-humiliation reaches its apogee with a line, translated as: “I’m the bitch at your doorstep.”

On Hussain embracing the Malamati tradition, Nain Sukh, who has recorded the oral histories of Hussain for 32 years, says Hussain would shave his face, remain publicly drunk and dance with tawaifs, khwajja siras, all of which would invite disrepute.

“In Sufism, the Murshid and Murid have always shared a special relationship, take Rumi and Shams Tabrizi, Bulleh Shah and Shah Inayat, Sarmad Kashani and Abhai Chand, Nizamuddin Auliya and Amir Khusro, and the relationship of Hussain and Madho follows in the same tradition. It is said that Bulleh Shah danced and sang in women’s clothing,” Nain Sukh says.

While Ahmad believes that the relationship between Hussain and Madho was platonic, Nain Sukh believes that there is more to it. “It has been recorded that the men would kiss each other and dance together. We cannot negate the fact the relationship between the two was both spiritual and physical. Some of his lyrics such as the desire to kiss his beloved’s feet, listening to the dictates of the Beloved’s eyes, and ‘being intoxicated by the Beloved’s eyes’ cannot be interpreted as love for the Almighty,” says Nain Sukh.

Story continues below this ad

Ahmad, however, says: “There is no trace of homoeroticism in Hussain’s poetry. While his poetry is romantic, it is directed toward the Almighty. Notably, none of the renowned Sufi poets of the Indian sub-continent got married or became part of any worldly institutions. However, there had to be a reason that after Madho’s death, which took place decades after Hussain, the locals decided to bury the two together.”

Both Ahmad and Nain Sukh allow that given that Hussain’s compositions were discovered decades after his death, some verses might be incomplete, lost in translation, misinterpreted, or re-interpreted to suit modern sensibilities.

Nazar also finds parallels with the legend of Sarmad Kashani and Abhay Chand. “Their relationship was normal for the times they lived in. Had they been doing anything considered transgressive at the time, there would be a record of it. One of the Sufi tenets is if you don’t love, how will you love the Almighty. Besides, Sufism did not subscribe to the Christian concept of celibacy. There is also a possibility that the legend was given a homosexual colour later. Even if this were true, it affirms that the society was extremely tolerant as Shah Hussain remains extremely popular to this day.”

Rubbina Gogi, an acclaimed Lahore-based post-impressionist painter, says, “Whatever the nature of their relationship, it was accepted and seen as natural. Taboos are a Western import, and have become normalised because of television, and modern-day parochial politics.”

Story continues below this ad

Mela Chiraghan: The Saint’s legacy endures

Each year in March, thousands of carousing devotees converge at the Saint’s shrine at Baghbanpura, near the Shalimar Gardens, in Lahore to celebrate his Urs (death anniversary). The festival is called Mela Chiraghan or the festival of lamps.

Mela Chiraghan was one of the biggest festivals in pre-partition Punjab. The twin cities of Amritsar and Lahore would become one as people from Amritsar would walk to the shrine in Lahore singing and dancing all the way. (X@Abbrar)

Mela Chiraghan was one of the biggest festivals in pre-partition Punjab. The twin cities of Amritsar and Lahore would become one as people from Amritsar would walk to the shrine in Lahore singing and dancing all the way. (X@Abbrar)

“Mela Chiraghan was one of the biggest festivals in pre-partition Punjab. The twin cities of Amritsar and Lahore would become one as people from Amritsar would walk to the shrine in Lahore singing and dancing all the way. Some verses, called ‘Sakhnia’, which had slightly vulgar verses were sung along the way. Large puppets would be created with phallic imagery and lamps would be lit across the city. Maharaja Ranjit Singh, the first Maharaja of the Sikh empire, would walk barefoot from his fort in Lahore to the Saint’s shrine, distributing alms (ashrafis) along the way,” says Ahmad.

Ahmad adds that the festival, while still popular, is not quite the same as before, especially after Pakistan’s former president Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq banned the playing of dhol and the use of phallic symbols. “The authorities are also concerned about the misuse of narcotics during the festival,” he says.

Even today, the three-day festival attracts large crowds where devotees sing and dance (the performance is called dhamaal) around a fire in red robes, evoking the image of a Sufi saint as a moth attracted to a Candle’s flame.

Even today, the three-day Mela Chiraghan festival attracts large crowds where devotees sing and dance (the performance is called dhamaal) around a fire in red robes, evoking the image of a Sufi saint as a moth attracted to a Candle’s flame.(Facebook/Pakistan Tours Tourism Guide)

Even today, the three-day Mela Chiraghan festival attracts large crowds where devotees sing and dance (the performance is called dhamaal) around a fire in red robes, evoking the image of a Sufi saint as a moth attracted to a Candle’s flame.(Facebook/Pakistan Tours Tourism Guide)

Gogi says, “While Mela Chiraghan is one of the few festivals from the pre-Independence era that have stood the test of time in Punjab, these days there are restrictions abound. Traditionally, the final day of the three-day festival was reserved for women, but this time authorities fixed the curfew at 10 pm.”

Gogi, who grew up listening to the Saints’ poetry, finds that the younger generation is taken with a different genre of music these days, and so the Saints’ legacy faces the danger of being relegated to obscurity.

Nazar agrees: “One reason why my paintings draw from the myths and legends of the land is because there is a looming danger of collective amnesia. At least, when one looks at the paintings one asks: who are the men in the painting and why are the chains vanishing. Thus, it is important to depict the politico-social realities of the day using our myths, symbols, and legends.”

The shrine and legend of Madho Lal Hussain is a testament to the pre-modern syncretic tradition, a medley of Hinduism and Islam, upper caste and lower caste, youth and experience, feminine and masculine, Murshid and Murid, Divinity and humanity, lover and the Beloved.

A pictorial depiction of the legend of Madho Lal Hussain and Dulla Bhatti, the Punjabi folk hero who led a revolt against the Mughal emperor Akbar, (right) the chains holding Hussain vanish even as Dulha Bhatti is executed. (Courtesy: Lahore-based painter and political cartoonist Sabir Nazar)

A pictorial depiction of the legend of Madho Lal Hussain and Dulla Bhatti, the Punjabi folk hero who led a revolt against the Mughal emperor Akbar, (right) the chains holding Hussain vanish even as Dulha Bhatti is executed. (Courtesy: Lahore-based painter and political cartoonist Sabir Nazar) The shrine where Shah Hussain and Madho Lal are buried at Baghbanpura, near the Shalimar Gardens, in Lahore, Pakistan. (Wikimedia Commons)

The shrine where Shah Hussain and Madho Lal are buried at Baghbanpura, near the Shalimar Gardens, in Lahore, Pakistan. (Wikimedia Commons) Mela Chiraghan was one of the biggest festivals in pre-partition Punjab. The twin cities of Amritsar and Lahore would become one as people from Amritsar would walk to the shrine in Lahore singing and dancing all the way. (X@Abbrar)

Mela Chiraghan was one of the biggest festivals in pre-partition Punjab. The twin cities of Amritsar and Lahore would become one as people from Amritsar would walk to the shrine in Lahore singing and dancing all the way. (X@Abbrar) Even today, the three-day Mela Chiraghan festival attracts large crowds where devotees sing and dance (the performance is called dhamaal) around a fire in red robes, evoking the image of a Sufi saint as a moth attracted to a Candle’s flame.(Facebook/Pakistan Tours Tourism Guide)

Even today, the three-day Mela Chiraghan festival attracts large crowds where devotees sing and dance (the performance is called dhamaal) around a fire in red robes, evoking the image of a Sufi saint as a moth attracted to a Candle’s flame.(Facebook/Pakistan Tours Tourism Guide)