India in the Olympics before Independence: Defining ‘Indianness’ under colonial rule

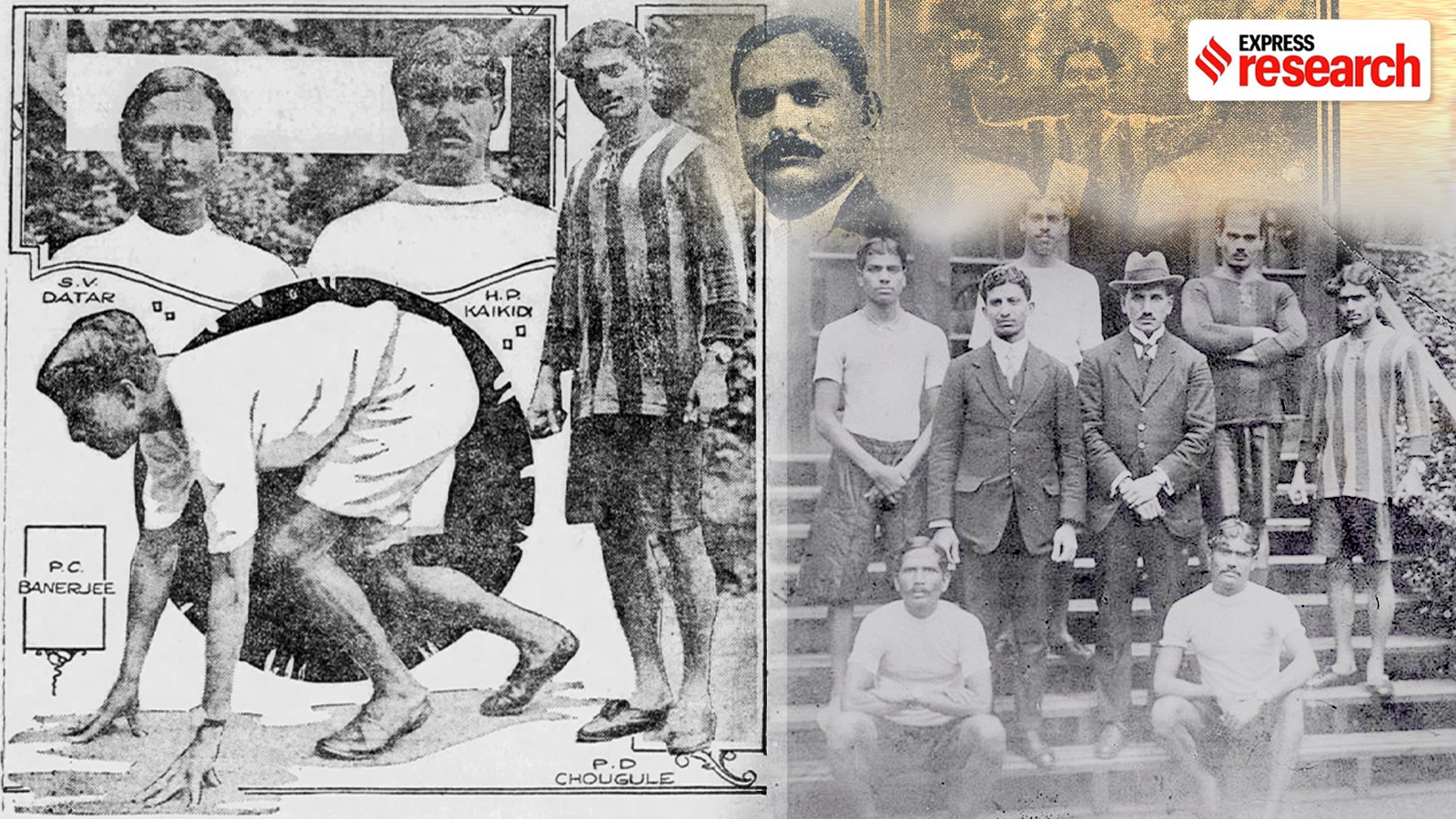

Not many know that P D Chaugule was the first Indian to compete in a marathon at the Olympics in 1920. Like Chaugule, many pre-Independence athletes are absent from India’s sporting history.

From questions of citizenship, fundraising, national identity and colonial patronage, several forgotten milestones led us to today. (Edited by Abhishek Mitra)

From questions of citizenship, fundraising, national identity and colonial patronage, several forgotten milestones led us to today. (Edited by Abhishek Mitra)Filmmaker Bipinchandra Chaugule is deeply engrossed in watching the ongoing Olympics. “Nowadays there is so much enthusiasm and patriotism associated with the Olympics,” he says. This was not the case in 1920 when his grand-uncle P D Chaugule competed in the marathon event. “The first question I am asked is, ‘Did he win a medal?’ That’s what people care about the most, but that’s missing the point. Simply going there makes him great,” says Bipinchandra. “It’s more than a gold medal, it’s a platinum medal,” he adds.

While P V Sindhu and Neeraj Chopra are household names, most pre-Independence athletes are absent from Indian history. What little is known about them is often clouded by mystery, judged simply from a sporting perspective, devoid of context, particularly, the challenge of making it to the competition in the first place.

Between 1900 and 1948, Indians faced an arduous process of Olympic qualification. From questions of citizenship, fundraising, national identity and colonial patronage, several forgotten milestones led us to today.

India’s first Olympian

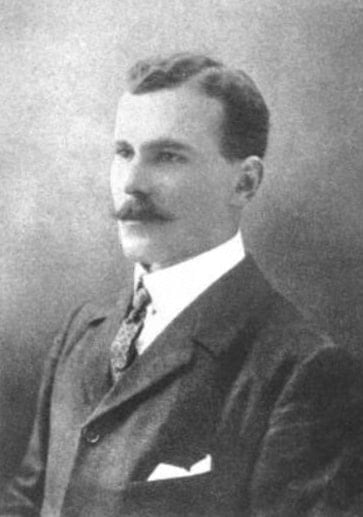

Norman Pritchard has taken on an almost mythical quality in the history of Indian sport. Born to two British citizens on June 23, 1875, in Calcutta, Pritchard was a gifted runner, although not much else is definitively known about him. According to Bengal Parish records, Pritchard visited London in 1900, presumably with no forthright knowledge that the relatively unknown Olympic games would be taking place in Paris later that year.

Although some claim that he simply wandered into the qualification event and registered as an athlete, the likelihood is that he went to England to compete and learned of the Olympics at local competitions whilst there. Informed largely by a 1998 article by Olympic historian Ian Buchannan, many believe that Pritchard represented England at the 1900 Olympics.

Norman Pritchard (Wikimedia Commons)

Norman Pritchard (Wikimedia Commons)According to Bipinchandra, Pritchard was not Indian. He says, “People often say he is Anglo-Indian. He is not. Just completely British.” By that reasoning, Bipinchandra argues, his grand-uncle should be recognised as the first Indian at the Olympics.

However, Gulu Ezekiel, a noted sports historian, and friend of the late Buchannan, insists that is not the case. Ezekiel, who has extensively documented what little is known about Pritchard, says that Buchannan’s 1998 article has been largely discredited. The British have a vested interest in claiming Pritchard as one of their own and have been at loggerheads with the American Olympic historians over several matters of citizenship, including that of Irish athletes.

According to Ezekiel, the bottom line is that the International Olympic Committee (IOC) has granted Pritchard’s two medals to India on their website. “Every four years, there is mass speculation about Pritchard,” he says, “but the IOC has given them to India and that is the end of the debate as far as I am concerned.”

Ezekiel also points to the fact that the Indian hockey team was credited with three gold medals during the colonial era and that in cricket, the Indian team is seen as a separate entity from the British. Additionally, South Korea, which was under Japanese occupation in the mid-1900s, has been credited for its athletes’ achievements during Japanese rule.

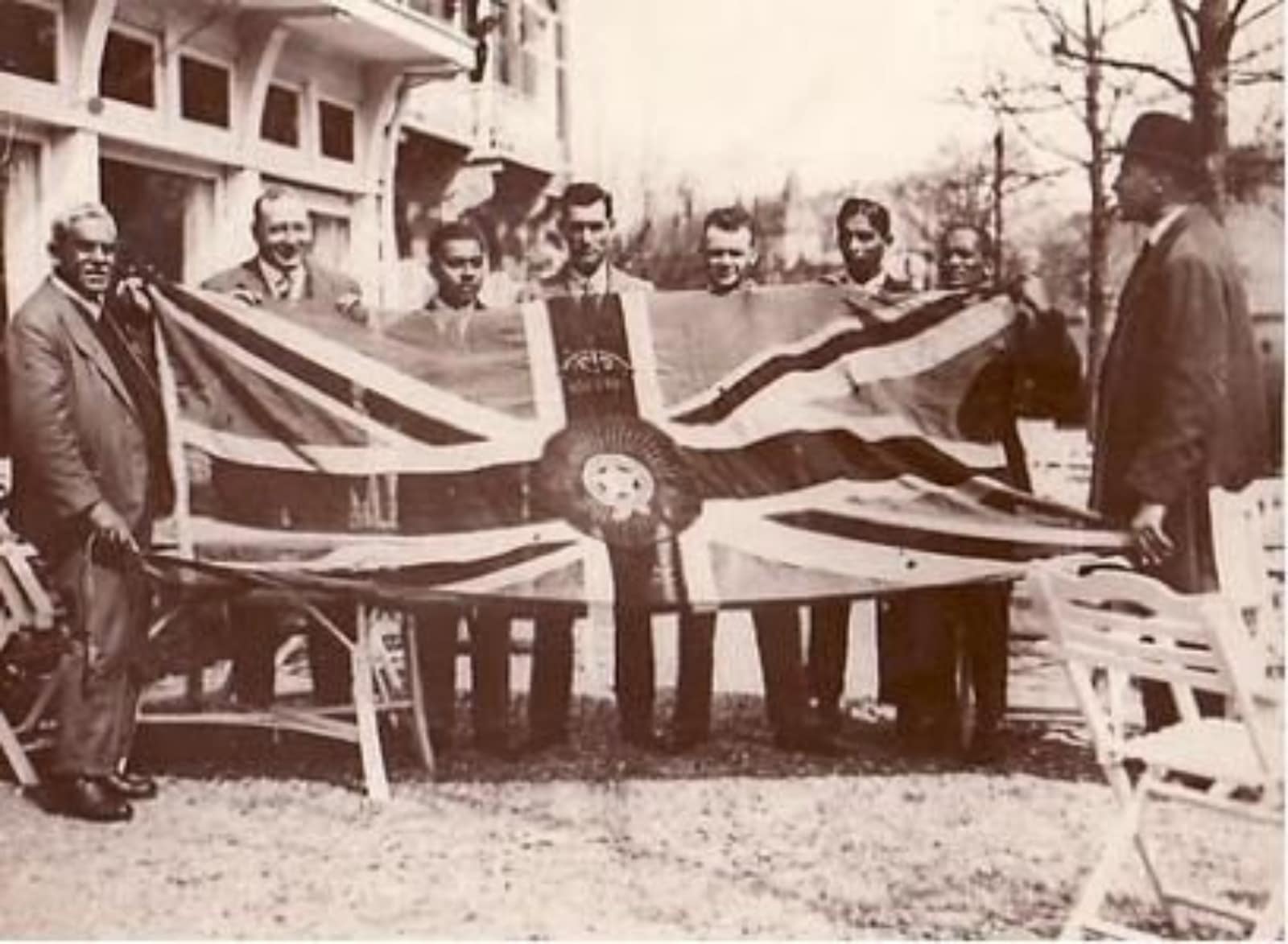

The confusion in this case likely stems from logistics. India first sent a national delegation to the Olympics in 1920 and its first official Olympic association was formed only in 1927. When the Indian hockey team won three gold medals, it was the British anthem that blasted through the stadium.

These semantics undermine what happened in reality. India has a long history of sporting achievement, although its formalisation largely occurred under the Company and later colonial rule. Until 1947, India as a country did not exist. We were a federation of different entities, bound together by the British. Although the concept of national identity was less coordinated during that time, the creation of the national Olympic association was very much an Indian endeavour.

The Indian Olympic Association

The credit for forming and funding the first Indian Olympic delegation belongs to Dorabji Tata, a prominent industrialist and scion of the Tata Group of companies. Like many of the Bombay mercantile class, Tata was educated at private institutions across Britain, which imbibed within him a great passion for sports.

Upon returning to India, in 1893, Tata instituted the formation of an athletic association of high schools in Bombay with the help of the school principals. Leading up to the 1920 Antwerp Olympics, Tata organised a sporting competition at Deccan Gymkhana in Poona, the first of its kind for Indian athletes. According to historian Boria Majumdar, Tata found that the boys, while physically talented, often came from poor backgrounds and were ignorant of European rules and modern training methods.

In Olympics: The India Story (2012), Majumdar writes that while Indians struggled with the shorter races, Tata was impressed by their performances in the long-distance races, particularly, the 25-mile marathon. Even running barefoot, the Indian athletes posted times comparable to their European counterparts. Struck by “a sense of wonder at this clash of peasant and Western cultures,” Tata personally financed sending three of the runners to the 1920 Olympics. This in turn, in his own words, “fired the ambition of the nationalist element in the city,” and according to Majumdar, “represented the birth of India’s Olympic encounter”.

Despite Tata’s efforts, raising funds for the event proved to be difficult. Majumdar writes that at this nascent stage, public money was not forthcoming and therefore the initiative was largely financed by a combination of money by “Tata, sundry princes, private collections – these increased substantially in later years – and interestingly, the Government of India”. Tata bore the brunt of the costs, however, and in exchange for his generosity, was asked to become chairman of the proposed Indian Olympic Association.

Although India came home without any medals from the Antwerp Olympics, by the time the Paris games rolled around in 1924, the country was far more organised in its efforts. This time, a nine-man contingent was sent to the games, selected not by Tata, but by a rigorous qualification process that would later be known as the National Games.

In the words of A G Noehren, leader of the Madras YMCA, the National Games (or Delhi Olympic Games as they were known at the time,) were truly a coordinated effort. He writes, “It is fair to state that these have been far more successful, have created a wider interest throughout the country and have produced more permanent results than any of us dared to hope for.”

Despite its popularity amongst the masses, the Indian Olympic Association was dissolved in 1926 and replaced by a body by the same name, hereon referred to as IOA. Although India had no permanent Olympic Association before 1927, the IOC allowed it to participate in the Antwerp and Paris Olympics to promote sports outside of Europe.

British India at the Olympics

After forming the IOA in 1927, the Indian hockey team won the country’s first medal in 1928. When one thinks about pre-Independence sport, the famous hockey team of Dhyan Chand is probably the first to come to mind. While their exploits will be touched upon further, it is also worth noting the contributions that came before them.

According to Bipinchandra, when he first contacted the IOA about the 1920 team that his uncle was a part of, they had no information to provide. “These babus don’t do anything,” he says scathingly, “all the information they now have is because of me.” It is unfortunate that few remember this team, who despite not winning any medals, accomplished a lot just by being there.

When the Indian hockey team won three gold medals, it was the British anthem that blasted through the stadium. (Personal Collection of Bipinchandra Chaugule)

When the Indian hockey team won three gold medals, it was the British anthem that blasted through the stadium. (Personal Collection of Bipinchandra Chaugule)

The six men came from modest backgrounds, including Chaugule who trained for his marathon by running from his school to his farm to his family’s printing press daily. When he ran, he felt like he was flying, Bipinchandra says, and he felt no fatigue whatsoever. Even before his first international competition, Chaugule inspired fear in the hearts of his competitors. Afraid of being beaten by a native, British soldiers would ask ahead if Chaugule was participating. If he was, they would drop out, his grand-nephew says.

For the men however, the conditions in Britain were starkly different from what they were accustomed to. For starters, the boat journey, undertaken in third class, was long and arduous. While Bipinchandra insists that the British did the best they could, they were also unsympathetic to the cultural needs of Indians. All the men were teetotaling vegetarians and struggled to cope with the diet, cold, and drinking culture of Britain. For the entirety of their trip, meals consisted of fruits, milk, plain rice and butter.

More importantly, the Indian runners were used to competing barefoot. According to Bipinchandra, his granduncle suffered from debilitating blisters on his feet that couldn’t be treated by the medicines of the time.

PD Chaugule (Personal Collection of Bipinchandra Chaugule)

PD Chaugule (Personal Collection of Bipinchandra Chaugule)In 1924, the conditions had improved, but there was still little money or glory associated with the games. When asked why, then, would people undertake the challenge, Bipinchandra said that while there was no known sense of national pride or animosity against British rule, the athletes saw the games as an opportunity to visit foreign lands and make their hometowns proud.

Arguably, the first correlation between the Olympics and nationalism occurred in 1928. While there were no overt demonstrations, tellingly, during the era of Indian hockey dominance, the British refused to field a national hockey team. In The Complete Book of Olympics (1982), historian David Wallechinsky notes, “Ever since India first appeared on the field hockey scene, Great Britain had studiously avoided playing the Indian team, apparently afraid of the embarrassment of losing to one of its colonies.”

Between 1928 and 1960, the Indian hockey team won seven out of eight Olympic gold medals. Apart from K D Jadhav’s bronze in wrestling in 1952, India won its first medal outside of hockey in 1996, when Leander Paes won a bronze in men’s tennis doubles. According to Ezekiel, hockey was the flag bearer for Indian sports, and was “in the forefront of patriotism and feeling of national pride”.

In a 2004 interview with the International Society of Olympic Historians, Feroz Khan, a member of the Indian hockey team that won gold in 1928, said that while the Indian team were dominant and well-regarded, marks of colonialism still ran rampant throughout the team. An example of that, he says, was the decision to appoint Oxford athlete, the Indian-born Jaipal Singh as the team’s captain. “The British influence was felt both on and off the field and British management was of the view that an Oxford-educated hockey captain would be better than anyone in India,” said Khan. Furthermore, as was the case till Independence, the Indian flag was the Union Jack and the victory anthem was ‘God Save the King’.

According to Singh, there wasn’t much public awareness about the games either and when the team sailed from Bombay harbour, only three people came to see them off. However, when they returned home triumphant, “Bombay made up for its earlier lapse, and gave us a welcome befitting Olympic champions.”

However, Brian Stoddart, an Australian academic at La Trobe University, argues that the formation and subsequent victories of the Indian Olympic delegations had little effect on nationalist sentiments. “Hockey wasn’t considered on the same level as cricket back then,” he says, “and while victories in cricket and football exposed the fallibility of Western superiority, hockey at the Olympics was seen almost like the sports version of Orientalism.”

There are several reasons behind this – from how the sport was introduced in India, the relative lack of nationalist sentiment amongst the athletes, and the nature of its patrons. However, as we will also observe, that alone, doesn’t paint the whole picture.

Sport and national identity

According to Stoddart, sports like cricket were introduced in India to civilise the natives. Much like Thomas Macauley’s theory on Western education, western sport was designed to teach Indians how to conduct themselves in a gentlemanly manner. For example, during a 1900 Indian cricket tour of England, a native fast bowler sought permission to play without footwear. His white captain responded, “Certainly not, my good man. This is England and a first class country to boot sir.”

Thus, says Stoddart, “Cricket was as much about social instruction, decorum and respectability as about physical exercise.”

Bipinchandra is aware of the relative lack of nationalist sentiment amongst early Indian athletes. He notes that as many Indians had connections to the British administration, and failed to recognise India as a coherent national identity, participating in the games was not a means of rebelling against British rule.

Perhaps, the best example of this approach comes from Ranjitsinhji, a cricketer and Maharaja of Nawanagar, patron of sports in India. Ronojoy Sen, author of Nation at Play: A History of Sport in India (2005), writes that Ranji is perhaps India’s best-known cricketing export, having more biographies written in his name than the likes of Sunil Gavaskar and Sachin Tendulkar.

However, despite funding India’s Olympic contingent in 1920, Ranji was not particularly interested in advancing sports in India. When asked to support the nascent Board of Control for Cricket in India (BCCI), he famously said, “I am an English cricketer and have not had the pleasure of seeing anything of Indian cricket.”

Nevertheless, as an undated Times of India report points out (and Sen quotes), “the service which Prince Ranjitsinhji has performed for India is not that he has proved one of his race to be capable of the highest achievement in our national spot, but that he has made the fact known to the whole British people.” While understated, that alone severely dented the notions of inherent British superiority.

In The Routledge Handbook of Sport in Asia (2020), sports historian Souvik Naha states that sports during the colonial era “was a sphere of simultaneously collaborating with and resisting the British,” becoming a symbol of resistance against colonial ideology. Thus, when India defeated a European team in cricket in 1906, it was celebrated as “a feat comparable with the military victory of Japan over Russia in 1905.”

Sporting victories became the personification of nationhood, and, according to Majumdar, “at a time where nationalist sentiment in India was gaining pace, the Olympics were the only international arena where Indian-ness could be projected on the sporting field.”

This was particularly evident during the 1936 Olympic Games in Berlin, when, according to George Orwell, “the imagined community of millions seems more real as a team of eleven named people. The individual, even the one who only cheers, becomes a symbol of his nation himself.”

It took on added significance as India was not invited to participate in the first British Empire Games (later the Commonwealth Games) in 1930. It was the country’s only opportunity to compete against the British on even terms, without the threat of reprisal or violence.

Following an eight-year break because of the Second World War, the 1948 Olympics took place in London, right after India gained its independence from the British. For the first time, India competed under the tricolour flag, without the prefix British attached. At those games, the British were finally forced to play against the Indian hockey team, losing by four goals in the final at Wembley Stadium.

Balbir Singh, who played the match, later summed up what it meant for the newly independent nation in an interview with the Olympics committee in March 2021. “The Tiranga rose up slowly. With our National Anthem being played, my freedom-fighter father’s words ‘Our Flag, Our Country’ came flooding back. I finally understood what he meant. I felt (I was) rising off the ground alongside the fluttering Tiranga,” he said.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05