How India’s independence movement influenced Korea’s struggle for freedom from Japanese rule

Newspaper clippings from the Korean peninsula under Japanese rule show that Gandhi’s aims of obtaining full independence from British rule through the Non-Cooperation movement that reached its peak in 1921, had an unexpected impact on the Korean independence movement.

By early 1922, Gandhi’s stature and awareness about the Indian nationalist leader had only grown in the Korean peninsula, and to such heights that Dong-A-Ilbo began referring to him as Mahatma Gandhi. (Courtesy: Santosh Kumar Rajan)

By early 1922, Gandhi’s stature and awareness about the Indian nationalist leader had only grown in the Korean peninsula, and to such heights that Dong-A-Ilbo began referring to him as Mahatma Gandhi. (Courtesy: Santosh Kumar Rajan)In a small park in central Seoul, lie clues about the little-known history of pre-Independence relations between India and the Korean peninsula. Two years before India attained independence from British rule, on the same date, the Korean peninsula had witnessed the end of 35 years of brutal Japanese occupation. Tapgol Park, a stone’s throw from Gwanghwamun, is the site of the March 1st Movement of 1919, that historians believe started the Korean independence movement in earnest. This park in South Korea also served as the location for the first reading of the Proclamation of Independence.

Tapgol Park in Jogno-gu, Seoul, South Korea, is the birthplace of the March 1st movement of 1919, against the Japanese occupation of the Korean peninsula. (Courtesy: Santosh Kumar Ranjan)

Tapgol Park in Jogno-gu, Seoul, South Korea, is the birthplace of the March 1st movement of 1919, against the Japanese occupation of the Korean peninsula. (Courtesy: Santosh Kumar Ranjan)

In the discourse surrounding freedom movements around the world that started a little before and after the end of the First World War, there is a belief among some Korean academics that India’s independence movement was inspired by the March First movement, explains Jawaharlal Nehru University’s Professor Santosh Kumar Ranjan, who conducts research on engagements between colonial India and the Korean peninsula. In actuality, Ranjan says, historical documentation indicates it may have been the other way around.

Some scholars consider the Jallianwala Bagh massacre of April 1919 to be the start of the independence movement in the Indian subcontinent, but Indian historians recognise that the fight for the country’s freedom struggle started much before the massacre. Ranjan says, “data shows that Gandhi wasn’t inspired by the Korean independence movement.”

In his research on the subject, one of India’s leading experts on Korea’s colonial history, Professor Pankaj Narendra Mohan writes that “it is erroneous to assume that the March First movement influenced India’s Satyagraha movement of 1919, waged for the repeal of the draconian Rowlatt Act.” According to Mohan’s research, when Gandhi first planned the Satyagraha movement, he had no information about Korean independence activists planning the March First movement for their own freedom.

The freedom movements in the Indian subcontinent and the Korean peninsula originated independently of each other, he finds. “But the example of the March First movement was used by Gandhi and other leaders of the Indian national movement to encourage youth to participate in the Non-cooperation movement that commenced in 1921 and the other subsequent nationalist movements,” Mohan writes.

Between 1910 and 1945, the Japanese empire annexed and occupied the Korean peninsula, following the Japan–Korea Treaty of 1876. The Eulsa Treaty, also known as the Japan–Korea Treaty of 1905, made the Korean peninsula a protectorate of Japan, that five years later, was formally annexed by Japan. The Korean peninsula gained independence from Japan after a 35-year struggle in 1945.

This belief among some Korean scholars that the March First movement inspired freedom movements against British rule in the Indian subcontinent may be attributed to an interpretation of the subcontinent’s history that analyses the freedom struggle on the basis of the intensity and the impact that protests and fights had on a wider, perhaps more global scale, Ranjan believes. “After the Jallianwala Bagh massacre, these nationalistic movements in the Indian subcontinent just became more strong and larger,” he adds.

Dr. Ock-soon Lee, director of the Institute of Indian Studies in Korea (IISK), told indianexpress.com, “Much before the March First Movement took place in Korea, the nationalist movement led by M.K. Gandhi was already in full swing in India. What happened later, thus I assume, cannot affect what happened earlier.”

“Korean scholars have had difficulty approaching (this subject)”, explains Lee Jeong-eun, president of the March First Independence Movement Memorial Society in South Korea, “because they did not have access to Indian historical data. So they could only insist that the (Indian independence movement) was a part of the new independence movements that were starting in Asia, the Middle East and Europe, by those oppressed by global imperialism. This needs to be further verified by Indian historical documents.”

Regardless of any dispute that may exist among scholars regarding historical timelines, there is a consensus that 1919 marked the beginning of the end of imperialism in several regions, including the Indian subcontinent and the Korean peninsula.

A photograph of Koreans protesting near the pagoda inside Tapgol Park in Seoul during the March 1st movement of 1919. (Courtesy: Santosh Kumar Ranjan)

A photograph of Koreans protesting near the pagoda inside Tapgol Park in Seoul during the March 1st movement of 1919. (Courtesy: Santosh Kumar Ranjan)What there is no dispute about, however, is how nationlistic movements in both the Indian subcontinent and the Korean peninsula influenced the other in many ways. While there had been religious exchanges between the two regions, Ranjan says the subjugation of both regions and the movements against these revived interest in each other in an unprecedented way. In the absence of official diplomatic relations, he points to how newspapers and other publications printed post 1919, generated awareness and curiosity of a shared plight and a desire for freedom from brutal occupation.

In 1920, when the Chosun Ilbo and the Dong-A-Ilbo newspapers launched their first editions, criticising Japan’s brutal policies, the imperial government deemed it to be subversive acts, often suppressing the newspapers’ operations. Ranjan has found at least 54 editorials that were published in Dong-A-Ilbo and Choson Ilbo between 1920-1930 that report on the Indian subcontinent’s fight against British colonial rule.

He says that these reports indicate how despite the absence of official diplomatic relations, the Korean peninsula was aware of and getting regular information about the Indian freedom movement, particularly Mahatma Gandhi. “There were almost daily reports on India’s Non-Cooperation movement of 1920-22 and the Civil Disobedience Movement of 1931-34.”

A photograph of Koreans protesting near the pagoda inside Tapgol Park in Seoul during the March 1st movement of 1919. (Courtesy: Santosh Kumar Ranjan)

A photograph of Koreans protesting near the pagoda inside Tapgol Park in Seoul during the March 1st movement of 1919. (Courtesy: Santosh Kumar Ranjan)

Newspaper clippings from the Korean peninsula under Japanese rule show that Gandhi’s aims of achieving self-governance and obtaining full independence from British rule through the Non-Cooperation movement that reached its peak in 1921, had an unexpected impact on the Korean independence movement.

In September 1921, Gandhi was introduced to Koreans in an editorial in the Chosun Ilbo titled ‘Mr. Gandhi, the real enemy of England’. That was followed by a series of articles in the same newspaper as well as the Dong-A-Ilbo with headlines like ‘The Savior of New India’ and ‘Gandhi: the hope of entire India’.

Ranjan says that by early 1922, Gandhi’s stature and awareness about the Indian nationalist leader had only grown in the Korean peninsula, and to such heights that Dong-A-Ilbo began referring to him as Mahatma Gandhi. In March that year, following Gandhi’s imprisonment by the British government, the newspaper published an editorial that said, “We respect Gandhi neither because of his status and position nor for his leadership qualities or political abilities. In fact, his commitment to truth and violence and his sacrifice of luxury and family pieties to come up with different hope of actions is respected by us.”

A copy of the January 8, 1910 edition of ‘India Opinion’ magazine published by Mahatma Gandhi, where the leader wrote about the assasination of Itō Hirobumi, Japan’s first prime minister, by Korean independence activist An Jung-geun, in retaliation for Itō’s role in the signing of the Japan–Korea Treaty of 1905 that allowed for Japan’s annexation of the Korea peninsula. (Courtesy: Santosh Kumar Ranjan)

A copy of the January 8, 1910 edition of ‘India Opinion’ magazine published by Mahatma Gandhi, where the leader wrote about the assasination of Itō Hirobumi, Japan’s first prime minister, by Korean independence activist An Jung-geun, in retaliation for Itō’s role in the signing of the Japan–Korea Treaty of 1905 that allowed for Japan’s annexation of the Korea peninsula. (Courtesy: Santosh Kumar Ranjan)

At least more than a decade before the Korean peninsula learned of the Mahatma, Gandhi had been writing about Koreans rebelling against Japanese occupation. In the January 1910 edition of the ‘India Opinion’ magazine, published by Gandhi, the leader wrote about the assasination of Itō Hirobumi, Japan’s first prime minister, by Korean independence activist An Jung-geun, in retaliation for Itō’s role in the signing of the Japan–Korea Treaty of 1905 that allowed for Japan’s annexation of the Korea Peninsula.

Gandhi cited the incident to highlight the evils of imperialism and its implications for the Indian subcontinent under British rule. “The man who fired the revolver-shot bluntly admitted that he had killed Itō because he could not bear to see Japan ruling Korea,” Gandhi wrote, referring to An. “It is said that Japan has killed nearly 12,000 Koreans to teach a lesson to the people. This lesson shows that power is an ugly thing…..Some of our young men believe that the British can be driven out of India by killing (some of them). Even if this is possible, it is not worth doing. Some things in Japan are commendable, but her imitation of Western ways does not deserve to be admired.”

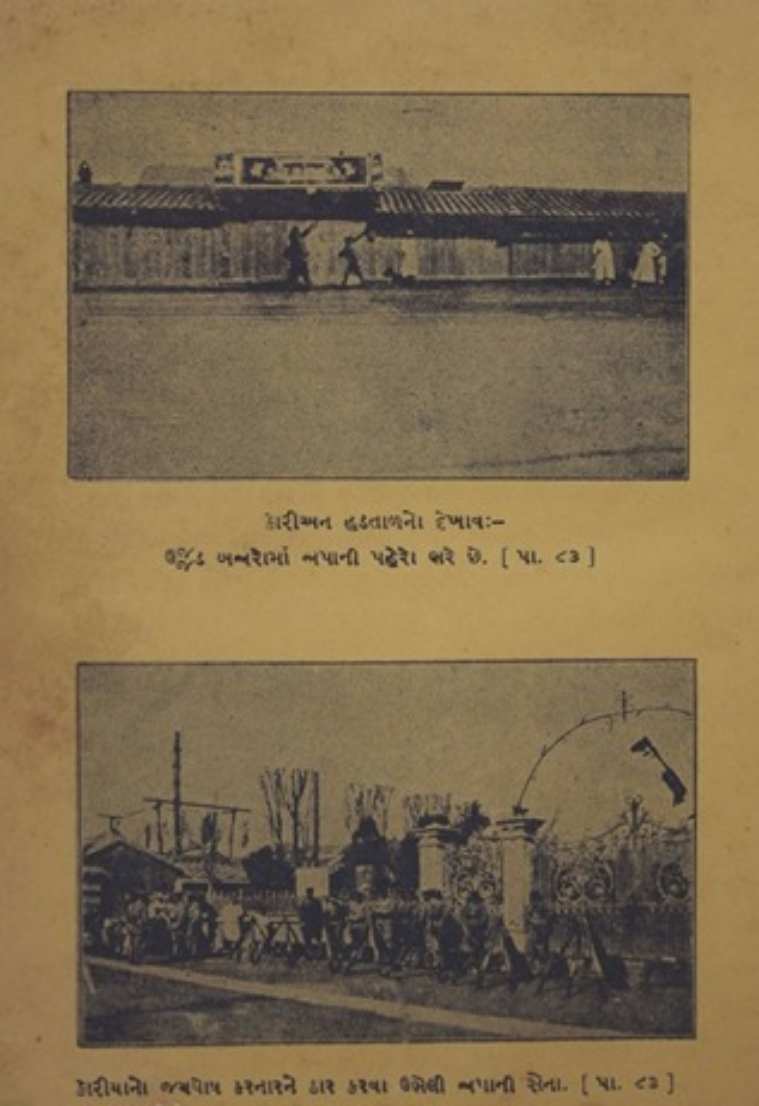

One of the earliest photographic documentations of the March 1st movement of 1919 in India was found in a Gujarati book. The image on top shows empty markets in the Korean peninsula being patrolled by Japanese soldiers. The image below shows Japanese soldiers barricading the entrance to Tapgol Park in Seoul to prevent Koreans from holding peaceful demonstrations against Japanese rule. (Courtesy: Santosh Kumar Ranjan)

One of the earliest photographic documentations of the March 1st movement of 1919 in India was found in a Gujarati book. The image on top shows empty markets in the Korean peninsula being patrolled by Japanese soldiers. The image below shows Japanese soldiers barricading the entrance to Tapgol Park in Seoul to prevent Koreans from holding peaceful demonstrations against Japanese rule. (Courtesy: Santosh Kumar Ranjan)

Ranjan believes it was Gandhi’s imprisonment in March 1922 and the agitation in the subcontinent that followed, that made a noticeably deep impact on leaders of the Korean freedom movement. Of Gandhi’s political beliefs and non-violent campaigns, the one that may have directly influenced Koreans fighting against Japanese oppression was perhaps the Swadeshi movement.

Korean nationalist leaders, Cho Man-sik, inspired by Gandhi’s Swadeshi movement, pushed for economic self-reliance for Koreans living under Japanese rule. (Wikimedia Commons)

Korean nationalist leaders, Cho Man-sik, inspired by Gandhi’s Swadeshi movement, pushed for economic self-reliance for Koreans living under Japanese rule. (Wikimedia Commons)Historical texts indicate that one of the most prominent Korean nationalist leaders, Cho Man-sik, inspired by Gandhi’s campaign to boycott of foreign goods by relying on domestic production, proposed supporting Korean industrial production and pushed for economic self-reliance for Koreans. In July 1920, Cho formed the Society for the Promotion of Native Production (조선물산장려운동) based on Gandhi’s aims through the Swadeshi movement.

Ranjan told indianexpress.com that Cho had gained exposure to Gandhi’s beliefs and work while attending college in Japan, a country that had more regular exchanges with Indian nationals than the Korean peninsula. Two years later, in December 1922, other nationalist leaders like Yom Tae-jin and Yi Kwang-su formed a group called the Self Production Association (자작회) in Seoul, to encourage the consumption of the local goods among the Koreans, similar to the Swadeshi movement.

A partial copy of the letter sent by the president of the Dong-A-Ilbo newspaper, Kim Sung-soo to Mahatma Gandhi in October 1926, asking the leader to send a message to the Korean people. (Courtesy: Santosh Kumar Ranjan)

A partial copy of the letter sent by the president of the Dong-A-Ilbo newspaper, Kim Sung-soo to Mahatma Gandhi in October 1926, asking the leader to send a message to the Korean people. (Courtesy: Santosh Kumar Ranjan)

Gandhi’s influence on the independence movement in the Korean Peninsula was perhaps so compelling, that in October 1926, the president of the Dong-A-Ilbo newspaper, Kim Sung-soo (Sungsoo Kim), wrote to the Indian leader: “You have inspired us, the Korean people, with hope and courage to follow after you; especially considering the cultural relationship which has existed between these two ancient nations since the past seventeen centuries, it is natural that the Korean people cherish the most sincere fellow-feeling with the people of “love” for whose deliverance you stand. India lives in our veins.….The name Gandhi, along with his four principles, is our jewel which is most treasured by us. To us you are not a stranger; you are our own beloved leader….”

During his research, Mohan discovered this two-page letter that Kim had to Gandhi, requesting him to send a message for the Korean people, along with his photograph with the intent to publish it in his newspaper. A month later, Gandhi’s letter and photo arrived in Korea, with a single line: “The message I can send is to hope that Korea will come to her own through ways absolutely truthful and nonviolent.” Kim published these on the second page of the Dong-A-Ilbo the next year.

Mahatma Gandhi responded to the request of the president of the Dong-A-Ilbo newspaper, Kim Sung-soo, sending a letter with a message for the Korean people fighting against Japanese rule, and a photograph that was subsequently published in the November 1926 edition of the newspaper.

Mahatma Gandhi responded to the request of the president of the Dong-A-Ilbo newspaper, Kim Sung-soo, sending a letter with a message for the Korean people fighting against Japanese rule, and a photograph that was subsequently published in the November 1926 edition of the newspaper.

During the course of his research, Ranjan found that Gandhi’s Dandi March or the Salt March, one of his most iconic acts of civil disobedience that occurred between March to April 1930, resulted in a flood of news reports being published in occupied Korea, making it the highest number of articles that had ever been published in relation to the Indian subcontinent.

Despite the absence of direct political and diplomatic engagement between pre-Independence India and the Korean peninsula under Japanese rule, the Indian subcontinent’s long struggle for freedom from colonial oppression inspired and influenced the much younger battle for independence that was playing out some 5,000 km away, sustained by the Koreans for 35 years.

Independence activist and writer Rahul Sankrityayan was one of the first few Indians to travel to the Korean peninsula and documented his travels extensively in his book titled ‘Japan’. In this photo from 1935, Sankrityayan is sitting with Japanese Buddhist monk, Ekai Kawaguchi. (Courtesy: Santosh Kumar Ranjan)

Independence activist and writer Rahul Sankrityayan was one of the first few Indians to travel to the Korean peninsula and documented his travels extensively in his book titled ‘Japan’. In this photo from 1935, Sankrityayan is sitting with Japanese Buddhist monk, Ekai Kawaguchi. (Courtesy: Santosh Kumar Ranjan)Awareness about Gandhi and the Indian subcontinent’s struggle for freedom was not limited to the educated and political class in occupied Korea, Ranjan explains. Sometime in the 1930s, independence activist and writer Rahul Sankrityayan became one of the first few Indians to travel to the Korean peninsula and documented his travels extensively in his book titled ‘Japan’. “Sankrityayan wrote that the shopkeeper showed him a book on Gandhi published in the Japanese language and added, ‘this shows how popular Gandhi is in Korea,” Ranjan says.

PM @narendramodi speaking at the unveiling of Mahatma Gandhi bust at Yonsei University : The solution to twin challenges of climate change and terrorism facing the world today, could be found in Mahatma Gandhi’s life and his philosophy . pic.twitter.com/b9mGyKk1Vy

— Arindam Bagchi (@MEAIndia) February 21, 2019

Perhaps little has changed in this context, close to nine decades later, in modern-day South Korea where Gandhi remains one of India’s most recognised political figures. In 2019, India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi unveiled a bust of Mahatma Gandhi in Seoul, in the presence of South Korean President Moon Jae-in, to mark the leader’s 150th birth anniversary. This statue, donated by India, was put on permanent display at Yonsei University’s campus in Songdo. But in readings of the history of both the Indian subcontinent and the Korean Peninsula, there is little mention of how freedom movements in both regions influenced the other.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05