The trailer release on YouTube attracted hundreds of viewers, sparking a wave of enthusiastic comments. Many hailed the book as a definitive account of India’s Independence and expressed eager anticipation for the series.

When Collins and Lapierre published their book in 1975, it quickly became a flashpoint for controversy. While lauded by some as a gripping, detailed narrative of India’s path to Independence and Partition, others criticised it for being sensational and biased. The controversy extended to claims of inaccuracies and ethical misrepresentation.

The earliest backlash both elevated and complicated the legacy of Freedom At Midnight, prompting readers to ponder: what is the true story of Independence?

A summary of the book

Published on October 1, 1975, Freedom At Midnight explored the pivotal events surrounding India’s struggle for Independence, with a focus on the year 1947 and the moments before and after the partition of British India.

Collins and Lapierre offered a thorough exploration of the dramatic transfer of power from the British Empire to the newly formed nations of India and Pakistan. The narrative centred on the historic midnight hour of August 14-15, 1947, when India shed its colonial past, marked by the lowering of the Union Jack. The celebrations were vast, with nearly a fifth of the world’s population rejoicing.

Beneath the euphoria, however, a darker reality awaited the 400 million people affected by the Partition. Violence, chaos, and mass displacement cast a shadow over this historic moment. The book highlighted key figures — Mahatma Gandhi, Jawaharlal Nehru, and Muhammad Ali Jinnah — whose actions profoundly shaped the turbulent birth of the nation. Lord Mountbatten, the last viceroy of British India, played a pivotal role, with his decisions leading to painful consequences that echoed throughout the newly formed nations.

Story continues below this ad

Disputed legacy of Freedom At Midnight

Freedom At Midnight encountered criticism for its portrayal of key figures and events surrounding India’s Independence and Partition. A major point of contention was the authors’ unwavering admiration for Lord Mountbatten. While they openly acknowledged this bias, their reverence for him undeniably shaped their depiction of his actions and decisions. Academic Leonard A Gordon, in the Journal of Asian Studies, wrote: “Human memory, even that of an earl, is selective and self-serving. One comes to believe that Mountbatten dispensed evenhanded justice, scarcely ever erred.”

In contrast, Muhammad Ali Jinnah’s portrayal was condemned as one-dimensional, with the authors repeatedly casting him as the sole architect of Partition. This persistent attribution of blame to Jinnah, without fully considering the broader political context surrounding Partition, according to Gordon, suggested, “If only Jinnah had not been so stubborn and vain and insistent upon being the leader of an independent Muslim nation, then the subcontinent would have been spared this great tragedy.”

The chapter on the lives of Indian nawabs, while rich in detail, raised eyebrows with some sensationalised depictions. For example, the Maharaja of Alwar was described as someone who “delighted in using children as tiger bait.” Gordon commented, “We learn about the vast wealth of the Nizam of Hyderabad and the sexual perversions of the Maharaja of Patiala. What do these details have to do with the achievement of Indian Independence? Nothing…such facts sell books.”

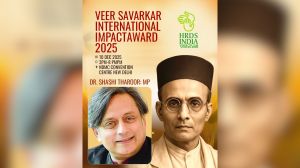

Similarly, the claim that Nathuram Godse had a homosexual relationship with his political mentor, Vinayak Damodar Savarkar, before embracing Brahmacharya, added an unexpected and highly personal element to the narrative. This assertion led Gopal Godse, a right-wing activist convicted of conspiring to assassinate Mahatma Gandhi in 1948, to demand a ban on the book.

Story continues below this ad

The authors faced reproach for focusing on inconsequential details and presenting them as key explanations. For example, they described a last-ditch effort by Mountbatten in July 1947 to secure Kashmir’s accession to India. When the Maharaja of Kashmir claimed to have an upset stomach and could not meet with Mountbatten, the authors explained, “A problem that would embitter India-Pakistan relations for a quarter of a century and imperil world peace had found its genesis in that diplomatic bellyache.”

They also faced backlash for placing full blame for the 1943 famine in Bengal on H S Suhrawardy, the Minister of Civil Supplies. A group of scholars argued that Suhrawardy had made a significant effort to combat the famine, which was caused by a complex set of factors, including wartime food demands for the army, disruption of Burmese rice supplies, a poor crop, and the Bengal government’s inability to control prices.

Collins and Lapierre offered a more balanced portrayal of Mahatma Gandhi. While they acknowledged his contradictions and the complexities of his statements, they also commended his leadership. However, Gordon argued that he was presented as “too convoluted and sex-obsessed for a Western reader to admire.”