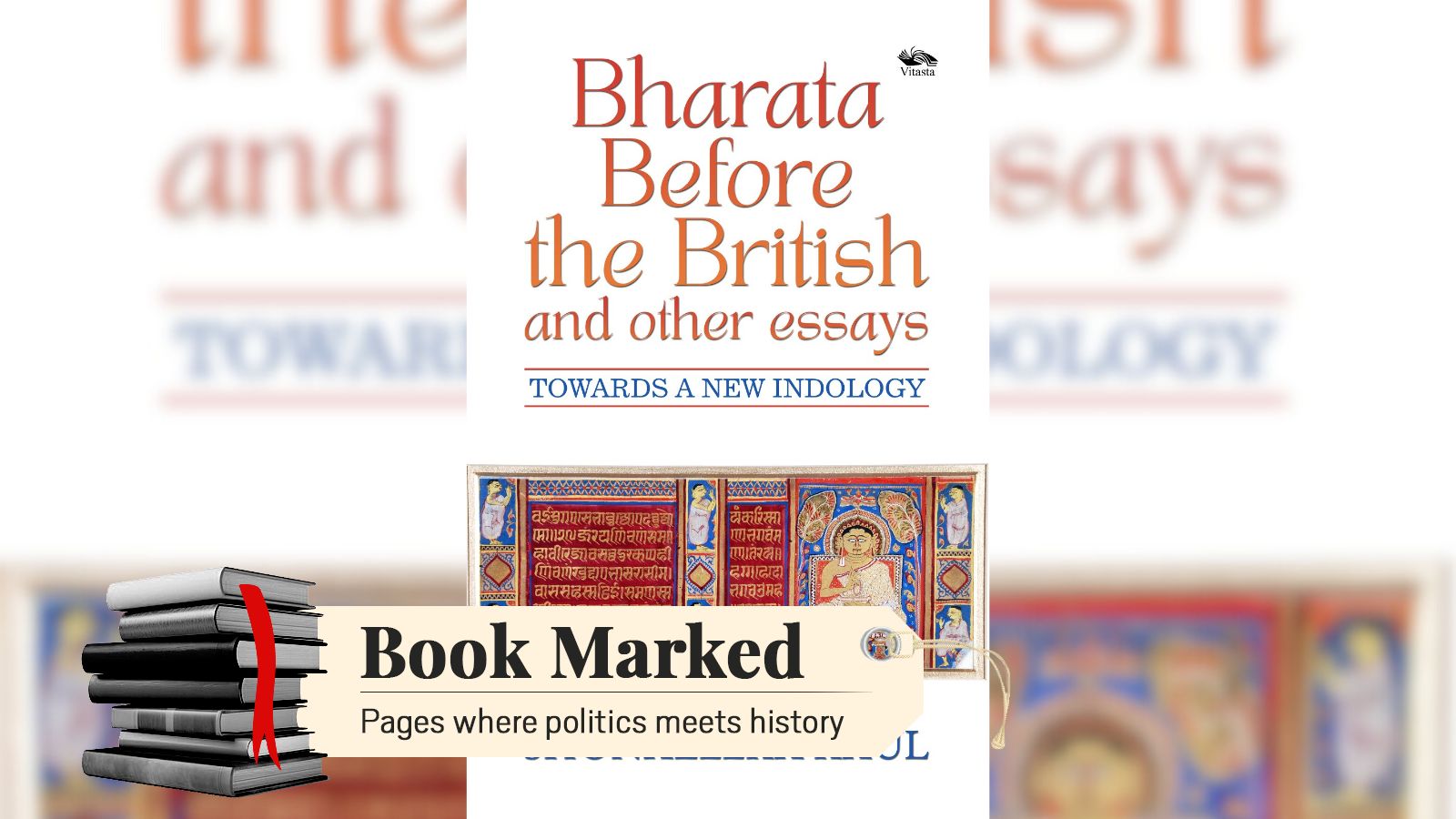

Published by Vitasta

Pages: 283

Price: Rs. 750

Professional historians emphasise a crucial word as part of their craft: historicisation. Good history writing remains alive to disjunctures and continuities as it studies the past and avoids being anachronistic by using present categories to look at the past.

Historian Shonaleeka Kaul, who teaches history at Delhi’s Jawaharlal Nehru University, has made a major intervention in this aspect of the historian’s craft in her just-released book “Bharata Before the British and other essays – Towards A New Indology”, published by Vitasta. Kaul delves into professional history writing on India since the 19th Century, a much politically contested space in contemporary Indian politics. She argues that colonial prisms have been widely used to view the country and Indian literary sources have been viewed from a lens that was used by the West to see non-western societies as the Other.

Rethinking history writing on India

Kaul breaks with much of the extant academic commonsense that prevails in India, and about India globally, by seeking to tease out new ways of sourcing the Indian past and questioning prevailing academic wisdom.

She argues that colonial writers saw India as a society with no sense of history, unlike the modern, “rational” West that had a sense of facts, chronology, and linearity. Kaul says that the prevalence of this belief even after Independence led to much ancient Indian literature being classed as myth and thus either not of much importance to the historian or a past instrument for disseminating the worldview of the social elite across society.

Kaul differs by arguing that myths are “communitarian mechanisms by which societies make sense of themselves and their world”, thus having a crucial role in “meaning-making for any society” and “identity formation for any demographic group”. She says that scientific historiography that ignored myths in the search for scientific past truths became an “agent of Empire” in India as it reinforced the colonial claim that while the West possessed history as a civilisation, there were non-western societies that possessed only myths.

She critiques the interpretation of epics such as Ramayana as representing a conflict between aggressing Aryans and non-Aryan tribals, saying that free-floating oral narratives circulating over the millennia cannot be reduced to an essentialist interpretation. Kaul calls for an approach where myths be reclaimed as “modes of territorial becoming and belonging” rather than dismissing them as ahistorical.

Story continues below this ad

India as a ‘felt community’

Theories on nationalism ranging from scholars such as Benedict Anderson and Eric Hobsbawm to Ernest Gellner see nationalism and nation-states as modern phenomena. For Anderson, nationalism in India becomes a discourse derived from the West. Taken together with a strong tradition of scholarship that saw British rule and the colonial modernity it ushered in as major disjunctures that both administratively united and altered the country, this body of scholarship sees India as a modern phenomenon.

What lay before it? Much research sees pre-modern times as lacking a sense of a pan-Indian community and being about webs of localised relationships that kept changing over time; of “fuzzy and fluid communities”, as Gyanendra Pandey put it.

Kaul breaks with this to argue that the notion of a “felt community” existed over the millenia in India. She distinguishes it from the modern nation-state, which is a recent form of political organisation across the world, but asserts that the notion of being a community bounded by the Himalayas in the north and the seas in the south comes repeatedly across historical sources, ranging from the Mahabharata, the Puranas, Tamil Sangam texts, testimonies of foreign travellers such as Al Beruni, and the writings of writers such as Amir Khusrao and Abul Fazl.

While historians are acutely aware of the disjuncture that modern technology, systems, colonialism, and mass mobilisation brought in societies, Kaul says this does not mean the absence of a “felt community” — borrowing a phrase from Rajat Kanta Ray — in India over the millennia.

Story continues below this ad

Sanskrit not elitist

Kaul also makes a break with another commonsense axiom of professional history writing: that Sanskrit was elitist and exclusionary, and Prakrits were the dialects that the common people used in early India. She says that on the contrary, Sanskrit was used for the wide dissemination of ideas through public plays and often had non-conformist content.

Asserting that “there is nothing inherently sectarian or hegemonising about Sanskrit”, Kaul says, “You only have to read a Kalidasa or a Shudraka to hear the Sanskrit litterateur speak truth to power, or a Bilhana and a Kalhana to glimpse the contempt in which they held almighty kings.”

She also cites texts that “lampoon and castigate social hypocrisies”, contesting D D Kosambi’s phrase that Sanskrit writers were the “housebirds of patricians”. She adds that the Natyashastra, India’s earliest work of dramaturgy in Sanskrit, says that “Sanskrit plays were performed at festivals, among other occasions, in public places such as temples and city squares”. The text calls drama the fifth Veda for all classes of society, Kaul writes. Recalling that the Natyashastra said a Sanskrit play must not contain obscure and difficult words, Kaul says that Sanskrit and Prakrit were often used in the same play.

Kashmir’s cultural links with the rest of India

A prominent historian of early Kashmir, Kaul devotes a few chapters to Kashmir’s historical cultural links with the rest of India, questioning the notion that it was historically unique and cut off from the rest of the country. She adduces evidence from the ancient to medieval times to show that Kashmir was always seen as part of the “felt community”; that pottery found there around the 6th century BC is of the same pattern as that found in the Ganga Valley; that Sanskrit was one of the oldest historical languages used there; that Kashmiri was related to the Indo-Aryan languages, and that the Sharda script of Kashmir evolved from Brahmi.

Story continues below this ad

Kaul laments that much research ignored the deep cultural ties of Kashmir with the rest of India because of contemporary political concerns, offering wide evidence for the point she makes in the context of early and medieval Kashmir.

She ends her book with chapters on history writing in India, questioning not just what she sees as a western lens to study India but also the neat division of historians in India between the Left and Right camps. She is also critical of the bureaucracy’s hold over academia in India and the API system that rewards papers published in journals aimed at increasing API scores rather than hard work leading to books with original arguments.