5 Lok Sabha seats in Punjab top poll spending list: A look at the numbers

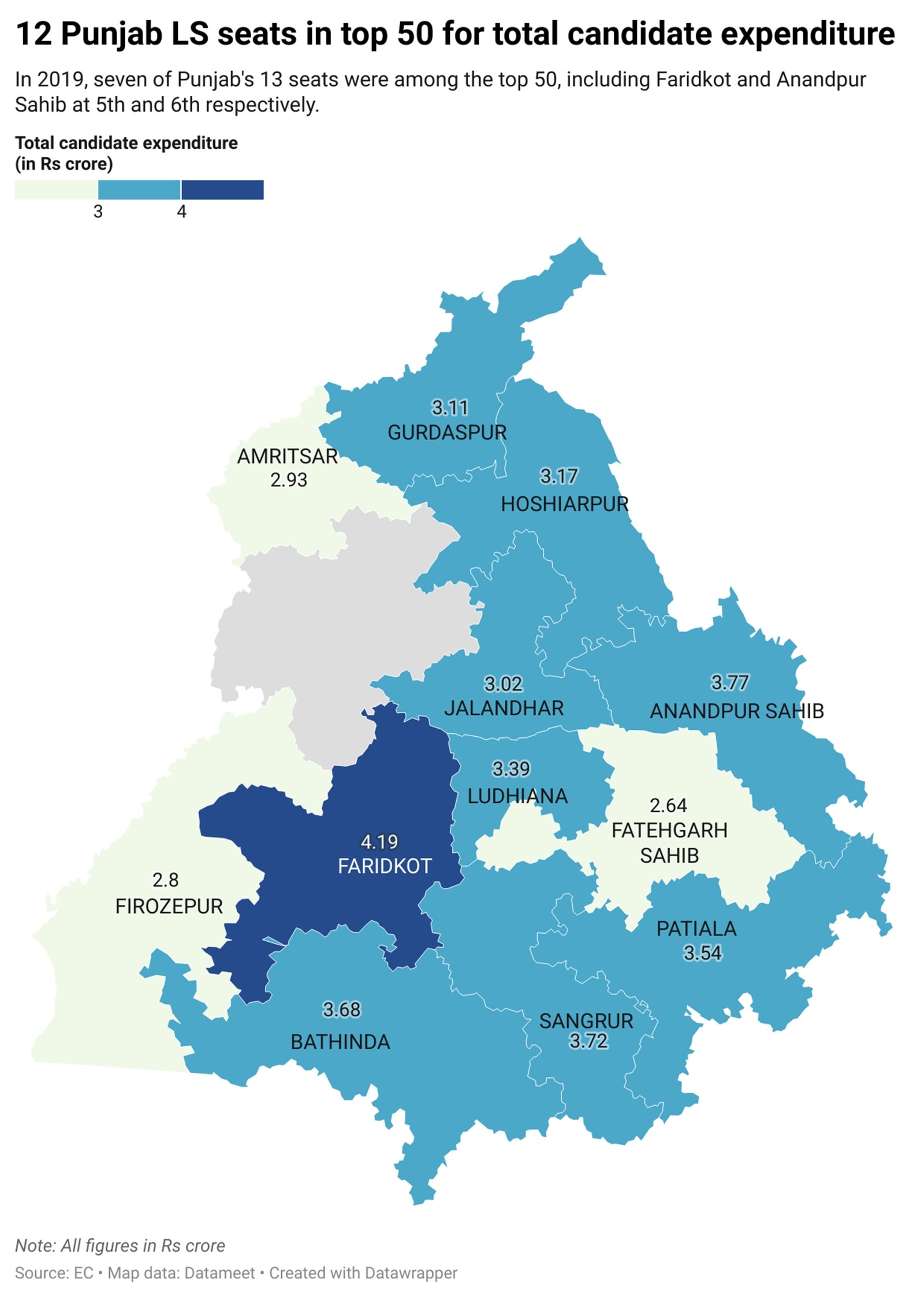

While candidates in Faridkot spent a total of Rs 4.19 crore, high-profile constituencies such as Anandpur Sahib, Sangrur, Bathinda, and Patiala round off the list.

In Faridkot, BJP’s Hans Raj Hans spent Rs 89.25 lakh, while AAP's Karamjit Anmol spent Rs 91.44 lakh. (Photos: X/ @hansrajhansHRH, @Karamjitanmol)

In Faridkot, BJP’s Hans Raj Hans spent Rs 89.25 lakh, while AAP's Karamjit Anmol spent Rs 91.44 lakh. (Photos: X/ @hansrajhansHRH, @Karamjitanmol)In the Lok Sabha elections last year, 12 of Punjab’s 13 Parliamentary constituencies were among the top 50 seats in terms of total candidate expenditure, data from the Election Commission’s recently published Atlas of the general elections shows.

All of the top five seats for overall candidate expenditure were in Punjab, with just one of the 12 constituencies outside the top 35 big spenders. According to experts, there are several factors why the spending is high in these Punjab constituencies — from candidates with a business background, such as real estate or liquor, that forces others to spend to the high number of parties in the fray.

The average expenditure declared by winning candidates across the country was Rs 57.23 lakh. In terms of overall expenditure by candidates, only seven states saw higher spending than Punjab. The highest spending state was Maharashtra at Rs 93 crore, more than twice Punjab’s Rs 42.4 crore.

Faridkot

Faridkot, where 28 candidates were in the fray, topped the list with an overall candidate expenditure of Rs 4.19 crore (in 2019, when the spending limit was Rs 75 lakh, it ranked fifth). Each candidate could spend up to Rs 95 lakh, as per the EC’s expenditure limits, with just five candidates accounting for 93.55% of the total spending.

Top spending seats in Punjab.

Top spending seats in Punjab.

Faridkot saw a high-profile contest between candidates from the state’s four major parties, though an Independent ultimately won. The ruling Aam Aadmi Party (AAP) fielded Karamjit Anmol, a Punjabi actor and singer, who spent Rs 91.44 lakh. The BJP’s Hans Raj Hans, a Sufi singer and former MP from Northwest Delhi, spent Rs 89.25 lakh while the Shiromani Akali Dal’s (SAD) Rajwinder Singh, the grandson of a former state minister, spent Rs 85.06 lakh. The Congress’s Amarjeet Kaur Sahoke spent Rs 84.06 lakh.

In the end, Sarabjeet Singh Khalsa, the son of Indira Gandhi’s assassin Beant Singh, won the election. Despite spending less than half his primary rivals at Rs 41.95 lakh, Khalsa managed to defeat the Anmol by more than 70,000 votes.

Despite the high levels of spending, all Faridkot candidates, except Khalsa and Anmol, lost their deposits for failing to secure at least one-sixth of the total votes.

“High expenditure involves many factors,” said Prof Ronki Ram, who teaches political science at Panjab University. “The stake of a candidate in the constituency, the issues, and the background of a candidate or their supporters. Normally, high spending happens where the candidate is in the business of real estate, liquor, or brick kilns, At times, money is spent to kill a strong wave emerging in the area. In Faridkot, the wave towards Sarabjeet Singh Khalsa was so strong that others had to up their scale.”

On average, each of the 543 Lok Sabha seats saw 15 candidates in the fray. But Punjab, with 25 candidates on average per seat, trailed only Telangana at 31. No seat in Punjab had fewer than 15 candidates, suggesting that the crowded fields likely resulted in increased expenditures.

“When the number of candidates increases, the contest becomes high-pitched. In addition to this, when celebrities come into the contest, the others too try to match their levels. Karamjeet Anmol and Hans Raj Hans fell in that category,” said a state government official.

Kuldip Singh who retired as an assistant professor from Punjabi University’s Department of Education and Community Service agreed that the number of parties in the fray played a role in pushing up spending. “An increasing number of parties also adds to the total expenditure. Above all, tickets are given to only those who are capable of spending money and have a good bank balance,” he said.

The other big spenders

After Faridkot, Anandpur Sahib had the next highest total candidate expenditure at Rs 3.77 crore, followed by Sangrur at Rs 3.72 crore, Bathinda at Rs 3.68 crore, and Patiala at Rs 3.54 crore, rounding off the top five.

The other top spenders were from Ludhiana, ranked eighth highest at Rs 3.39 crore, followed by Hoshiarpur at 11th with Rs 3.17 crore, Gurdaspur at 13th at Rs 3.11 crore, Jalandhar at 16th with Rs 3.02 crore, Amritsar at 17th with Rs 2.93 crore, Ferozepur at 20th with Rs 2.8 crore, and Fatehgarh Sahib at 34th with Rs 2.64 crore. Khadoor Sahib was the only Punjab seat not to figure in the top 50.

Among these constituencies, Bathinda (11th among high-spending constituencies in 2019) also saw a high-profile contest. The SAD’s Harsimrat Badal, the wife of former party chief and Deputy CM Sukhbir Badal and daughter-in-law of former CM Parkash Singh Badal, won the seat for the fourth straight time. Her poll expenditure was Rs 93.24 lakh, the eighth-highest amount spent by any candidate across India.

Sangrur that ranked third for candidate spending in 2024 (it was 14th in 2019) gained prominence after CM Bhagwant Mann won the seat in 2014 and again in 2019. Mann’s Dhuri Assembly seat also falls within Sangrur, as do those of three state Cabinet ministers: Harpal Singh Cheema, Aman Arora and Barinder Kumar Goyal. Last year, the AAP’s state youth president Gurmeet Singh Meet Hayer won the seat.

The Congress’s Vijay Inder Singla, who won the seat in 2009, attributed the high expenditure to the constituency’s political prominence. “There are so many issues in this constituency that once you start campaigning, you need to reach out to every voter carefully,” he told The Indian Express.

The other big-spending constituencies also saw high-profile fights, including Anandpur Sahib that ranked second behind Faridkot (it was sixth in 2019) and Patiala that was fifth in 2024 (and 17th in 2019).

While the high candidate expenditures can be attributed in part to the number or prominence of the candidates, Pramod Kumar of the Institute of Development and Communication in Chandigarh pointed out that campaign expenditure is not limited to what the candidates individually declare.

“The actual amount of money spent in an election is much more than what is shown in the figures. The EC must provide an estimated expenditure per constituency, including the party’s expenses. Also, the new trend of giving guarantees to ensure votes should also be counted as expenditure as this burden later falls on the state’s or the country’s exchequer,” he said.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05