Known to history largely for his campaign demanding complete integration of Jammu and Kashmir with India, Syama Prasad Mookerjee had a stellar career, both as an academic and a public figure. With the Supreme Court on December 11 finally giving its seal of approval to the Narendra Modi government’s decision to abrogate Article 370, Mookerjee’s role in pushing the Sangh’s oldest ideological project and reshaping Indian politics is again in focus.

Born on July 6, 1901, Mookerjee — the son of Calcutta High Court judge Ashutosh Mookerjee, who was also Vice-Chancellor of Calcutta University (CU) — had a brilliant academic career that took him from Presidency College, Calcutta, to Lincoln’s Inn in London. Mookerjee also achieved the distinction of becoming the youngest V-C of CU at just 33 years.

He was elected to the Bengal legislative council in 1929 and 1930, first as a Congressman and then as an Independent. He found his way to the Hindu Mahasabha in 1939 at a time of great churn in the Indian freedom movement and two years later joined the Progressive Coalition government of Fazlul Haque of the Muslim League with whom he had differences. But he remained the Finance Minister in the government till 1942, justifying his decision by saying that what was required was organising Hindus and their cooperation with Muslims who believed in joint work by the two communities. A controversial letter against the Quit India Movement written by Mookerjee to the British has also been talked about by many writers during this time.

From 1943 to 1946, Mookerjee was the Hindu Mahasabha president and took up the cause of Bengal Hindus in the run-up to Partition. He opposed the United Bengal plan of Muslim League leader and Bengal Prime Minister H S Suhrawardy. The plan called for a separate Bengal independent of both India and Pakistan, something Mookerjee saw as nothing but the domination of Hindus by a Muslim majority. Instead, he called for the partition of Bengal, with Hindu-majority West Bengal staying within India.

Moderate Hindutva

Though a Hindutva ideologue, Mookerjee represented its moderate wing. After the assassination of Mahatma Gandhi, he made the Mahasabha’s Working Committee adopt resolutions that “expressed shame that Gandhi’s assassin had been connected with the organisation, and declared support for the government in its efforts to suppress… subversive activities in any shape or form”, writes B D Graham in his book Hindu Nationalism and Indian Politics. Significantly, he resigned from the Mahasabha in November 1948 because the party rejected his suggestion that it either stay away from politics to remain a Hindu cultural outfit or open itself to non-Muslims if it wanted to continue to be a modern political party. In both these contexts, Mookerjee came across as a moderate Hindutva voice.

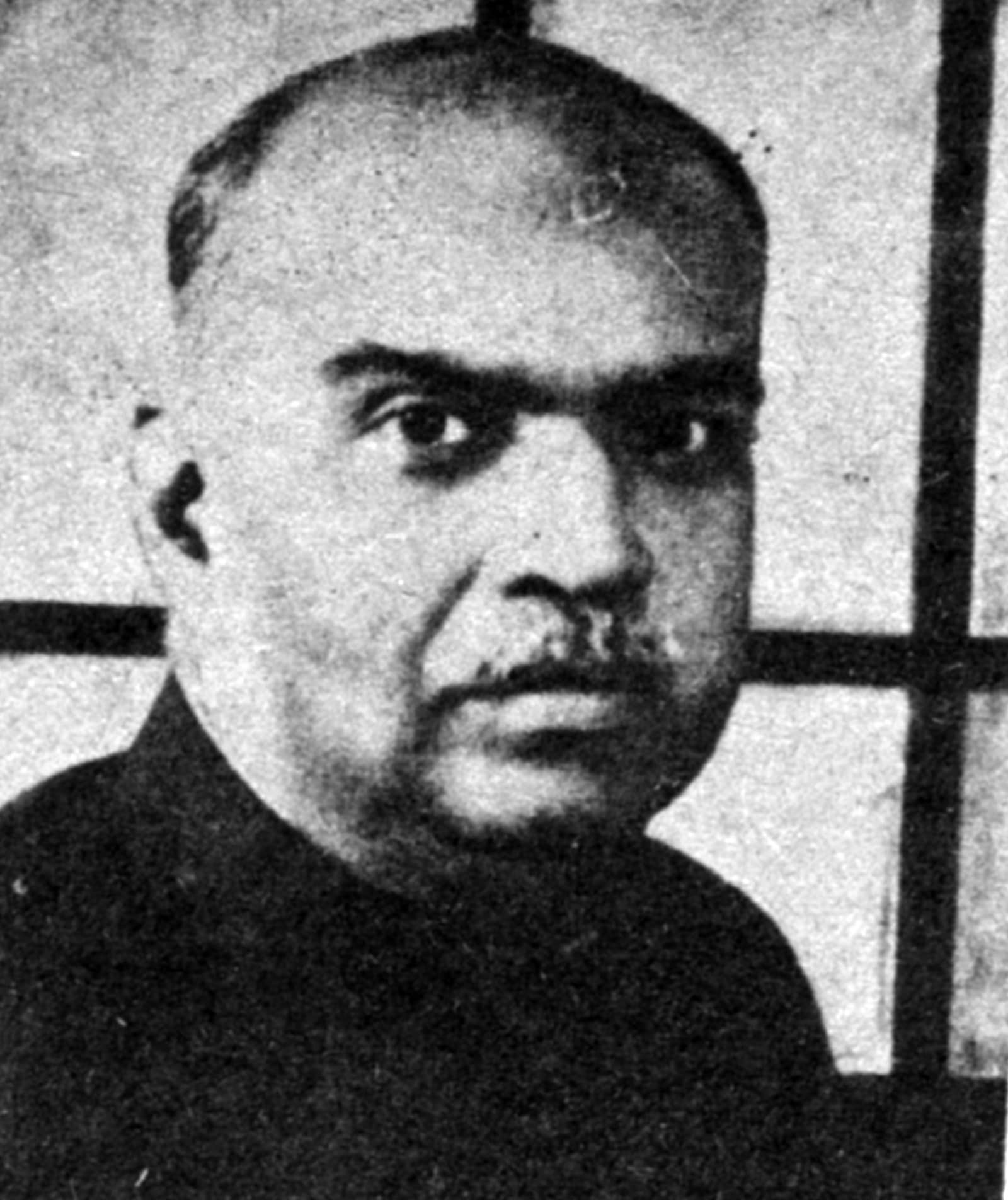

Dr Shyama Prasad Mukherjee, Founder of Jan Sangh. (Express Archive Photo)

Dr Shyama Prasad Mukherjee, Founder of Jan Sangh. (Express Archive Photo)

But he stuck to the cause of justice for Bengali Hindus even after Partition, when he raised his voice against the “persecution” of Hindus in East Pakistan, leading to a steady stream of refugees coming to India. At the time, the minister of Industry and Supply in the Jawaharlal Nehru government. But he resigned in 1950 following differences over the Nehru-Liaqat pact and the following year, he formed the Bharatiya Jana Sangh with the help of RSS volunteers and began to prepare for the first general elections of 1952. The new party won just three seats. Its leader was eminent but the party had failed to take off.

Kashmir’s special status and pushback

Mookerjee soon came to associate himself with a cause that would offer him a place in India’s political history forever — Kashmir.

Story continues below this ad

Following the war of 1947 over Kashmir and the UN-mediated ceasefire that brought the Line of Control into existence, UN Security Council Resolution 47 asked both sides to demilitarise so that a plebiscite could be held to determine the wishes of the people of J&K. Since demilitarisation never happened on either side, the resolution remained a dead letter. However, the Nehru government thought that Kashmir required special constitutional provisions. To institutionalise this, Article 370 of the Constitution gave Parliament powers only on defence, foreign affairs, and communication in the case of Kashmir. Indian laws didn’t apply to Kashmir beyond these three heads, people from outside required a permit to visit the state and were barred from buying land there.

The state’s Prime Minister Sheikh Abdullah abolished big land holdings in J&K in 1951 under the Big Landed Estates Abolition Act, without giving any compensation, hitting hard Hindu landlords from the Dogra community. He also adopted Urdu as the official language. As a result, resentment brewed among the landlords.

In protest, the Praja Parishad of Prem Nath Dogra, a former RSS swayamsevak and civil servant from Jammu, launched an agitation against the Sheikh Abdullah government in February 1952. In Parliament, the Jana Sangh took up the arrest of Dogra and his followers after a clash with the police in the state on February 8, 1952. Later, the Jana Sangh also opposed the adoption of a flag for the state by the Constituent Assembly of J&K. On June 26, 1952, Mookerjee pressed the Centre to convince J&K to accept full integration with India. The Jana Sangh and Prajna Parishad widely adopted a slogan: “Ek desh mein do vidhan, do pradhan aur do nishan nahin ho sakte (in one nation, there cannot be two Constitutions, two Prime Ministers and two flags)”.

The Praja Parishad also rejected the Delhi Agreement that the Nehru government and J&K administration signed in July 1952 as part of which the state accepted the jurisdiction of the Supreme Court and the supremacy of the Indian flag. However, the state’s flag would also continue to remain in use. As part of the agreement, the state further accepted the President of India’s power to declare a state of Emergency under Article 352 with the concurrence of the state in the event of internal disturbances.

Story continues below this ad

By late 1952, the Parishad launched an agitation when the J&K Assembly elected Karan Singh, the son of J&K’s last monarch Raja Hari Singh, as the head of the state (Sadr-e-riyasat). Dogra and other Praja Parishad leaders were again arrested.

At its first annual session at Kanpur in December 1952, the Jana Sangh passed a resolution supporting the Praja Parishad’s Jammu Satyagraha for the state’s complete integration with India. Nehru saw the orientation of the Jana Sangh as “communal” on this question, writes B D Graham. The Jana Sangh then decided to go into agitation mode. Atal Bihari Vajpayee who became private secretary to Mookerjee in the beginning of 1953 was sent across the Hindi-speaking states to popularise the agitation. In Delhi, Jana Sangh workers would suddenly emerge in parks and shout slogans demanding the full integration of Kashmir.

In May 1953, Mookerjee escalated the protest by going to J&K without a permit, a symbolic rejection of Kashmir’s special status. Vajpayee accompanied him. On May 11, 1953, he crossed the Ravi by road into J&K and was arrested by the state police. He told Vajpayee to return to Delhi and tell everyone that he had entered the state without a permit if only as a prisoner, writes Abhishek Choudhary in his recent biography of Vajpayee. Mookerjee was kept in a cottage about eight miles from Srinagar. He was, however, a heart patient with a blood pressure problem and could not cope with the new setup. On June 23, he died of a massive heart attack.

What he left behind in the Hindu nationalist movement was a sense of “martyrdom” for Kashmir. L K Advani used to recall how a journalist in Rajasthan informed him that Mookerjee was no more and how the Jana Sangh plunged into deep mourning. In allied organisations of the RSS, there is a popular slogan: “Jahaan hue balidaan Mookerjee, wo Kashmir hamara hai; jo Kashmir hamara hai, wo saare ka saara hai (where Mookerjee was martyred, that Kashmir is ours; the Kashmir that is ours is the full Kashmir)”.

Dr Shyama Prasad Mukherjee, Founder of Jan Sangh. (Express Archive Photo)

Dr Shyama Prasad Mukherjee, Founder of Jan Sangh. (Express Archive Photo)