BJP says Congress caused B R Ambedkar to lose elections. This is what happened

Ambedkar lost from Bombay North Central in the 1952 general elections and a by-election from Bhandara two years later, both times to Congress candidates. He resented the losses, though he remained a Rajya Sabha MP

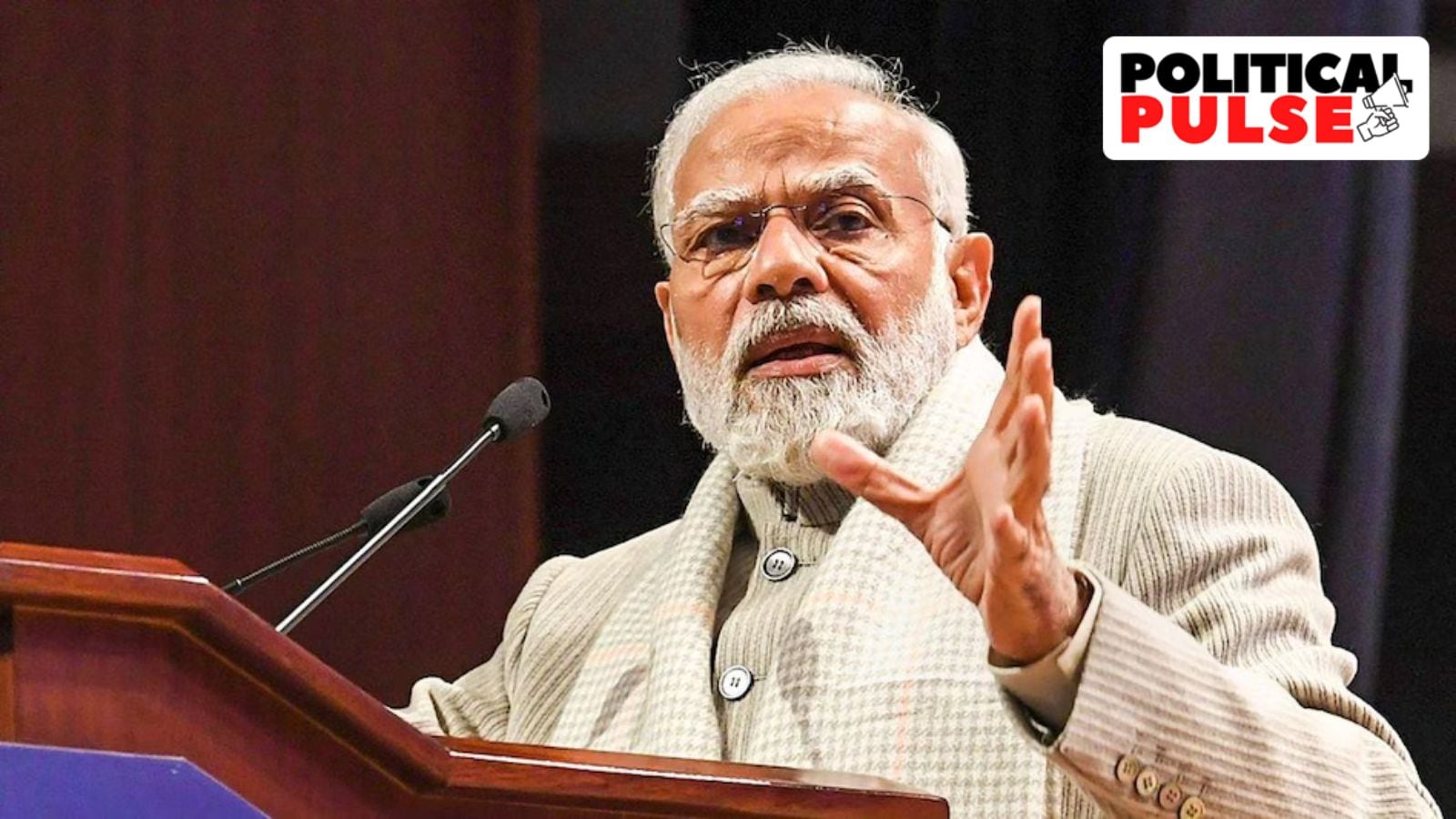

Prime Minister Narendra Modi defended Union Minister Amit Shah and also accused the Congress of spreading “malicious lies” and listed its “sins towards Dr Ambedkar”, including “getting him defeated in elections not once but twice”. (PTI)

Prime Minister Narendra Modi defended Union Minister Amit Shah and also accused the Congress of spreading “malicious lies” and listed its “sins towards Dr Ambedkar”, including “getting him defeated in elections not once but twice”. (PTI)As the Opposition raised the heat on the government over Union Home Minister Amit Shah’s remarks on B R Ambedkar, asking Narendra Modi to take action against him, the Prime Minister defended Shah. Modi also accused the Congress of spreading “malicious lies” and listed its “sins towards Dr Ambedkar”, including “getting him defeated in elections not once but twice” and “Pandit Nehru campaigning against him and making his loss a prestige issue”.

So what was Modi talking about?

Nehru had picked Ambedkar in his 15-member Cabinet in the first government of the Union of India, appointing him the Law Minister. The Congress dominance was at its peak at the time, but even before the first elections in 1952, various political forces were coming up. Syama Prasad Mookerji, the industries minister under Nehru, formed the Bharatiya Jana Sangh, which decades later became the BJP. Ambedkar himself had formed the Independent Labour Party (ILP) in 1936, and had floated the Scheduled Caste Federation (SCF).

In an article titled “Democracy’s Biggest Gamble: India’s first free elections in 1952”, published in World Policy Journal in 2002, historian Ramchandra Guha wrote that Ambedkar had sharply attacked the Congress around this time “for doing little to lift up the lower castes”.

“It was the same old tyranny, the same old oppression, the same old discrimination … After freedom had been won, said Ambedkar, the Congress Party had degenerated into a dharamsala (rest home), without unity of purpose or principles, and open to all, fools and knaves, friends and foes, communalists and secularists, reformers and orthodox and capitalists and anti-capitalists,” Guha wrote.

The first general elections were held between October 1951 and February 1952, with Ambedkar contesting from Bombay North Central. The Socialist Party led by Ashok Mehta supported him. This was a dual-member constituency, where a general candidate and a Scheduled caste and/or Scheduled tribe candidates would contest from a seat, a practice prevalent in the country till 1961. Heavyweights such as Communist Party leader S A Dange contested the elections. Ambedkar lost to the Congress’s Narayan Sadoba Kajrolkar by 15,000 votes.

Following his loss, Ambedkar questioned the outcome. “How the overwhelming support of the public of Bombay could have been belied so grossly is really a matter for inquiry by the Elections Commissioner,” a PTI report quotes him as saying on January 5, 1952.

Ambedkar and Mehta filed a joint election petition before the Chief Election Commissioner to set aside the result and declare it null and void. They claimed, among other things, that an “aggregate of 74,333 ballot papers had been rejected and not counted”.

Sociologist Gail Omvedt wrote about this in Ambedkar: Towards an Enlightened India, saying: “In 1952 both Socialists and Dalits fared badly. Ambedkar himself lost in his stronghold of Bombay, blaming the defeat on the Communists. Indeed, the voting bases for the Communists and Ambedkar were in the same area of Bombay—the textile mills, where Dalits and OBCs had long settled and laboured.”

“Ambedkar took the case to court in January 1952, charging electoral fraud against the Communists, headed by S.A. Dange. The argument was simple: in the electoral system of the time, reserved constituencies were lumped with general constituencies, and voters had two votes, one for each seat. There were 78,000 invalid votes, half of these for Dange, and Ambedkar claimed that Communists had propagated against him that voters cast both their votes for one candidate, which was illegal. Although he lost the case, Ambedkar’s anger was not assuaged. He continued to hold a seat in Parliament, as a member of the Rajya Sabha, but this meant an ongoing dependence on the Congress,” Omvedt wrote.

In 1954, Ambedkar contested a second election, a bypoll from the Bhandara constituency in Maharashtra. This time, he lost to the Congress candidate by about 8,500 votes. During this campaign, biographer Dhananjay Keer wrote in his book Dr Ambedkar: Life and Mission, Ambedkar made a “frontal attack” on Nehru’s leadership, criticising his foreign policy in particular.

In Ambedkar: A Life, Congress MP Shashi Tharoor wrote, “The general elections of 1952 did not go well for Ambedkar. Partly this was because he underestimated the hold of the Congress Party, the political embodiment of the country’s nationalist movement, on the imaginations of the electorate, and partly because Ambedkar did not realize how unpopular some of his positions were in the eyes of the general public. When he contested the Bombay North seat, he was the principal draftsman of the Constitution, and the pre-eminent leader of the working class and the Scheduled Castes; yet he lost to his former assistant, the Congress Party candidate Narayan Sadoba Kajrolkar. The Congress nonetheless appointed Ambedkar a member of the upper house, the Rajya Sabha. Ambedkar did not relish that position, resenting his dependence on his old enemies, and sought to enter the Lok Sabha again, in a 1954 by-election from a constituency called Bhandara. This time he fared even worse, placing third. Once again, it was the Congress Party that won the seat. A sullen Ambedkar remained in the Rajya Sabha.”

Political scientist Christophe Jaffrelot wrote in a 2010 article in the Indian International Centre Quarterly that the election showed that the SCF remained confined to Maharashtra and could not attract voters beyond Ambedkar’s own Mahar community.

According to Jaffrelot, the Republican Party of India, which Ambedkar formed in 1956, was open “to other groups such as religious minorities, lower castes and aborigines, rather than only to Dalits”. “This approach would ensure the rise of RPI in the 1960s. It is this perspective that the Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP) was to follow even more successfully later,” he wrote.

- 0115 hours ago

- 0215 hours ago

- 0315 hours ago

- 045 hours ago

- 0515 hours ago