Once notorious for crime, voters in this part of Bihar tilt towards NDA but corruption a sore point

Though voters in the Bagaha region of Paschim Champaran complain about red tape and “afsarshahi (bureaucrat rule)”, some of them say “nobody wants Lalu raj back”

A tribal household in Lakshmipur, Valmikinagar. (Photo: Deeptiman Tiwary)

A tribal household in Lakshmipur, Valmikinagar. (Photo: Deeptiman Tiwary)

Through the late 1980s and 90s, the Bagaha region in Bihar’s West Champaran district witnessed so many kidnappings, robberies, and murders that the government converted it into a police district to manage crime. Flanked on the north by the Valmiki Nagar Tiger Reserve stretching into Nepal and by Uttar Pradesh in the west, it allowed criminals to flit across inter-state and international borders. On top of that, a crippled Bihar Police under Lalu Prasad did not help matters.

With a significant tribal population living on the margins of the jungles stretching up to Motihari, the Bagaha region was also a hotbed of Maoist activity at the time because of the Maoist Communist Centre. The situation was brought under control only when the Nitish Kumar government took the reins of power.

“Nobody could venture out of their house after the sun had set. Now people return home past midnight. We cannot forget that. Though the incumbent MP (Sunil Kushwaha of the Janata Dal-United) has neither visited the region nor got any work done, nobody wants Lalu raj back,” says Bagaha resident Pradyumn Tiwari when asked about his electoral preference.

This vote-for-law-and-order sentiment, for which several voters credit Kumar, sustains in Champaran across several caste groups. But there is little patience for red tape and grassroots corruption. Both the Valmiki Nagar Lok Sabha seat, of which Bagaha is a part, and the Paschim Champaran constituency vote in the sixth phase on May 25.

“Pehle daaku raat mein aate the, ab din mein kursi par baith ke dakaiti karte hain (Earlier, dacoits used to come at night, but now they are in power and rob us in daylight). No one can get any work done without bribes here,” says Kishandev Pandit, a Kumhar (OBC) farmer from Kapaardhikka village, about 20 km from Bagaha town. Pradeep Pandit, who makes iron gates, agrees and says there is a mood for change this time.

At Dhokaraha Bazar near Ramnagar, Ramakant, a Bania (OBC); Manoj Sahu, a Gond (tribal); and Parmeshwar Chauhan, a Nonia (OBC), blame Nitish Kumar for “institutionalising afsarshahi (bureaucrat raj)” and corruption.

About 15 km away in Narkatiaganj, it is no different. Santosh Chaudhary who sells “nimbu paani (lemonade)” for a living says, “Modi is giving free ration and housing. But you get one kg less ration because the dealer keeps one kg. Those with concrete houses are getting Awas Yojana money because they can bribe. It is fixed at 20-30%. The ward members will get your picture clicked in front of some poor man’s house and give you the money. Modi ji se desh surakshit hai, lekin local corruption se gareeb pareshan hai (The country is safe because of PM Modi but local corruption has the poor troubled),” he says.

The fight in Valmiki Nagar

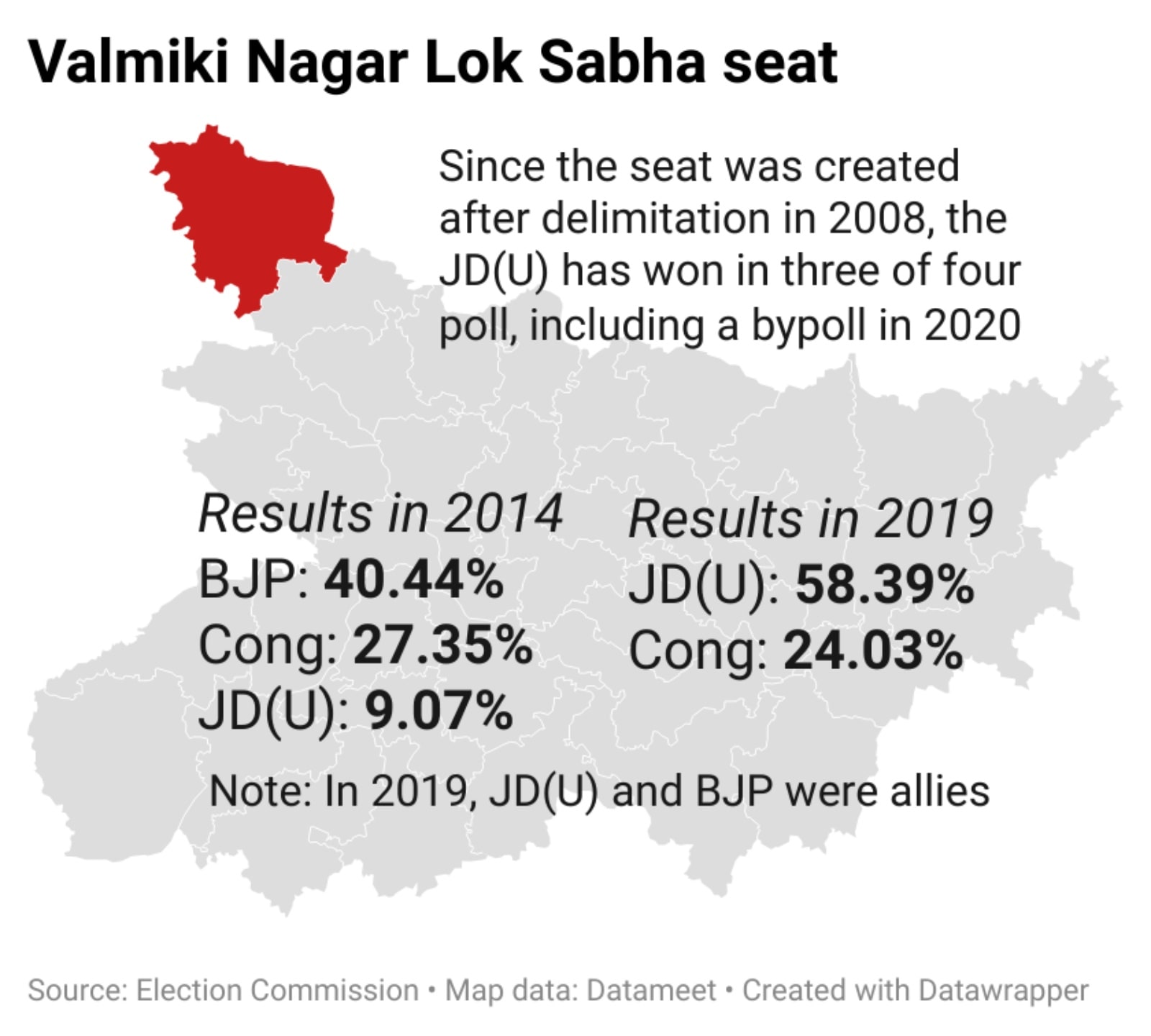

Valmiki Nagar witnessed a close contest in 2019, with the Congress losing to the JD(U) by 22,000 votes. The constituency is dominated by Brahmins (over 2 lakh voters), tribals (around 2 lakh), Muslims (around 2 lakh), Yadavs (around 1 lakh), and Dalits (around 1 lakh), apart from a significant chunk of Mallahs (EBCs). This time, the JD(U)’s Sunil Kushwaha is pitted against RJD’s Deepak Yadav, who owns a local sugar mill.

Yadav was campaigning for the BJP till a month ago and even distributed T-shirts with Modi’s pictures. When the seat went to the JD(U) as part of the seat-sharing arrangement, Yadav switched to the RJD. The RJD candidate wields considerable influence in Bagaha and appears to have recall value among voters because of the effort he has made in the past couple of years.

Valmiki Nagar Lok Sabha seat

Valmiki Nagar Lok Sabha seat

A Tharu (tribal) from Mahdeva village on the margins of the Valmiki Nagar Tiger Reserve, Tejpratap Kaji, says that Yadav has been prompt in paying local sugarcane farmers. “But Modi’s ration is also coming and young men from our villages have got jobs. Maybe we will think about the RJD in the Assembly polls. Tejashwi needs to be given a chance,” he says.

Despite all the talk of the RJD making Valmiki Nagar a contest, the Modi vote appears intact in the tribal belt as well. Barring the Sikta region, where CPI(ML) has considerable influence, most tribals appear happy with Modi’s schemes and Nitish’s hold over law and order.

“People want peace and that has been established over the past 15 years. The poor will work hard and earn. But earlier whatever we earned was snatched away by criminals,” says Mangal Prasad, a Tharu from the tribal village of Bairia Tola.

In the tribal-dominated villages of Lakshmipur and Semara, there are some dissenting voices. Deep Narayan Urao who runs a tribal organisation in the area says the Modi government changed the law and now people don’t get arrested under the SC/ST Act. “Our people do not have the wherewithal to influence the police. The upper caste have it and thus get away with their offences,” he says.

Deepak Kumar, 35, a Gond from Semara, declares that this time he will be voting for change. “We are unhappy with both Modi and Nitish. There are no jobs. All the young people in the state are forced to work in other states,” he says.

However, Dinesh Urao, a paan shop owner in Lakshmipur issues a word of caution. “Do not draw quick conclusions. The RJD voter is loud, the Modi voter is silent,” he says.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05