Achieving consensus at G20, Modi takes global centrestage, can he step across the deepening faultlines at home?

Can G20-like consensus be forged nationally, with the Opposition? It’s not that PM does not have a Jaishankar to do it for him on the political front. But then the question is: does he feel the need for it?

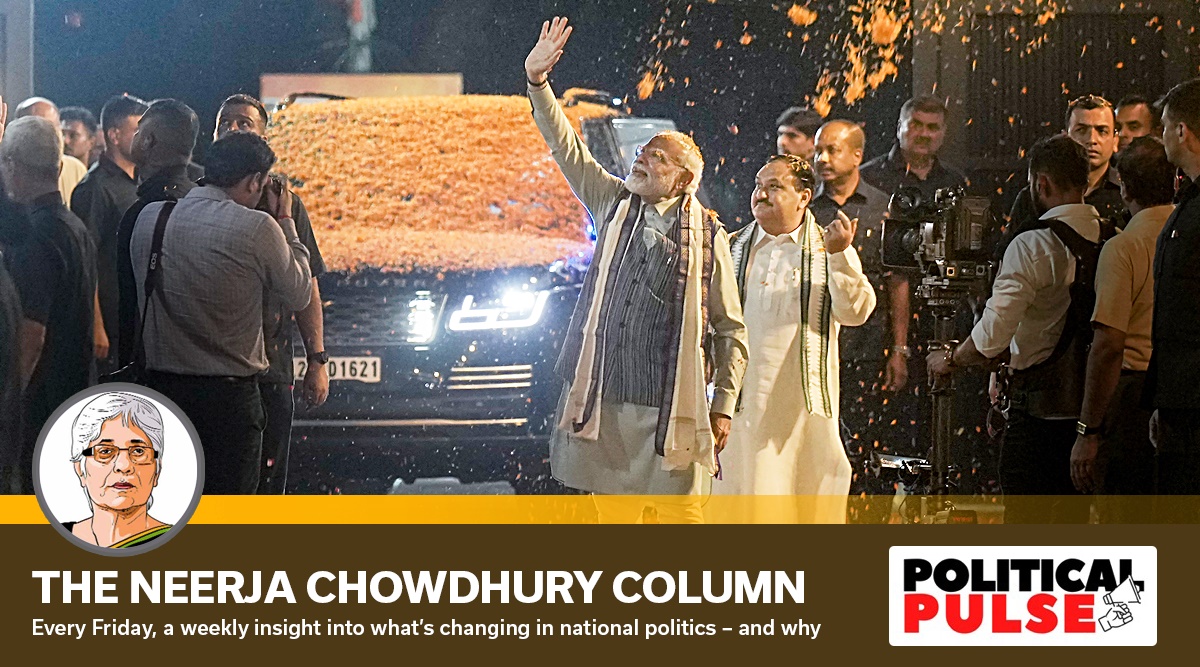

The non-English speaking Modi with his chaiwalla background and OBC credentials clawed his way up to the pinnacle of power –and with equal determination to the global high table. (PTI)

The non-English speaking Modi with his chaiwalla background and OBC credentials clawed his way up to the pinnacle of power –and with equal determination to the global high table. (PTI)

With the success of the G20 Summit in Delhi, is Narendra Modi making a mark globally as Jawaharlal Nehru did on the world stage after Independence? India’s first prime minister had carved out a niche for the country as the leader of the non-aligned movement even though it was at the time seen as poor and backward. Today, Modi strides on the global stage at the head of the world’s fifth largest economy.

Not long ago, Karan Singh, who had worked with every prime minister, compared Modi to Nehru. “(I suspect) he will never admit this but he would like to be another Nehru and to surpass him.”

Many have often compared Modi to Indira Gandhi – not so much to Nehru, who the BJP-RSS love to dismiss. Indira, like Modi, was a strong leader, did not brook opposition, went beyond her party to become a mass leader, drew criticism for weakening institutions – and ruled through her PMO.

The erudite, Harrow-Cambridge-educated, aristocratic Nehru, brought up in sprawling Anand Bhavan, was loved by the Indian masses because he had thrown himself in the freedom movement and gone to jail many times to secure India’s Independence. One of the reasons why Mahatma Gandhi chose him as the Congress president in 1946, who later went on to become the prime minister, was his ability to deal with the British, which would smoothen India’s transition to a free, sovereign nation.

The non-English speaking Modi with his chaiwalla background and OBC credentials clawed his way up to the pinnacle of power –and with equal determination to the global high table. This is the story of the devolution of power enabled by India’s democracy – and it resonates with an aspirational India today. He is effectively leveraging India as a growing market and the West’s need to contain China in the region. (The India-West Asia-Europe Corridor announced at the Delhi Summit to counter China’s Belt and Road initiative is the latest case in point.)

Modi borrowed a leaf from the Nehru book at the G20 conclave despite the two leaders being poles apart ideologically – Nehru the convinced secularist mindful of the rights of the minorities, and Modi with his Hindu civilisational project which may be further unpacked if he secures a third stint in power.

The five-day special session of Parliament starting September 18 is also expected to give more of a glimpse into the BJP’s agenda for the future, Bharat vs India and “One Nation One Election” being a foretaste of what may come.

The world applauded India’s deft diplomacy in managing to get the Delhi Declaration adopted. India managed to maintain its neutrality over the Russia-Ukraine war which was expected to cast a shadow on the Summit. Many were sceptical whether a Delhi Declaration would be possible, after China and Russia’s top leaders, Xi Jinping and Vladimir Putin, had decided to give the event a miss.

Unlike in Bali last year, the Declaration this time did not condemn Russia for aggression. And though Ukraine was unhappy, its allies (US, UK, France and others) accepted it. Both sides wanted to keep India on their right side. Clearly, a majority (those not taking sides) prevailed. India enabled the Global South to come centrestage, even as it also played a critical role in bringing the 55- nation African Union (AU) into the G20. China too was not unhappy.

Modi, like Nehru before him, had succeeded in walking the neutral, middle path.

The G20 struck a high note for many Indians – and showcased what India was capable of. The spectacle of the world leaders, led by PM Modi, standing together to pay homage to Gandhi, the father of the nation – an apostle of non-violence – at Raj Ghat sent its own message. (Even as the Ukraine war continued to rage on, defying a solution. Or that the Gandhian institutions are under attack.)

The Delhi Summit, in evolving a consensus, showed that India’s Prime Minister has arrived on the world stage. It was only in 2013, when Modi was declared the BJP’s prime ministerial candidate that people had wondered how he would handle issues of foreign policy in an increasingly complex world.

Modi seized every opening that India ‘s presidency of G20 provided, to showcase India as a confident country, a rising power, a nation to be wooed, a preferred destination for investment. India’s art, culture, history and hospitality, its kaleidoscopic colours and diversity – captured at the Bharat Mandapam and earlier in state capitals and smaller towns – were used to the full.

Even Chandrayaan-3 and the subsequent Solar mission have struck all the right chords for India to be seen as a nation on the march. As is Modi’s wont, everything had to be “bhavya” (grand), its message amplified for the maximum possible impact.

Above all, Modi has shown he is capable of building consensus, navigating a difficult terrain, displaying flexibility, with a crack team of diplomats hard at work – it took all of “200 hours” to hammer out a consensus declaration.

Can this consensus be forged nationally, politically? It’s not that the PM does not have a S Jaishankar to do it for him on the political front. But then the question is, does he feel the need for it domestically as much as he did internationally to make a mark?

This then is the story of two Modis, and the G20 has drawn attention to it – one in evidence at the Bharat Mandapam, embracing world leaders, effecting a breakthrough. And the other, who did not invite Leader of Opposition Mallikarjun Kharge to the presidential dinner for the G20 delegates. (It did not help that Kharge skipped the Red Fort Independence Day function. Or that Congress leader Adhir Choudhary took to task West Bengal Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee for attending the G20 dinner.)

A bitterness has been growing across the political spectrum in the country. The latest decision of the Opposition INDIA alliance to boycott certain TV anchors and the decision of the BJP government in Manipur to file FIRs against journalists for their fact-finding report has only deepened these divides.

Contention is undoubtedly the warp and woof of politics, and we are now entering the election season. But, and this was underlined yet again by the success of the G20 meet, a country as diverse and varied as India needs consensus to run it, a give and take on both sides. That is the real challenge facing Modi as he prepares for a shot at his third stint in power and for the Opposition as they mount their bid to wrest power from him.

(Neerja Chowdhury, Contributing Editor, The Indian Express, has covered the last 10 Lok Sabha elections. She is the author of the recently published How Prime Ministers Decide)

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05