Opinion Why women prefer Modi’s BJP

The BJP has strategically embraced the concept of selfless service as a central theme in its political narrative. This unique approach championed by Modi permeates the party’s messaging, events and grassroots activities

The BJP’s success story among women is not confined to the ballot box. (PTI)

The BJP’s success story among women is not confined to the ballot box. (PTI) The BJP’s resurgence in recent elections in Rajasthan, Chhattisgarh, and Madhya Pradesh leaves the INDIA bloc with a tantalising but hard battle if it seeks to make a credible dent in Narendra Modi’s bid for re-election in 2024. Since 2014, various factors have been attributed to the BJP’s electoral dominance. While conventional explanations revolve around the four M’s — the charismatic appeal of brand Modi, Hindutva messaging, the BJP’s well-oiled organisational machinery, and its access to monetary resources — a fifth M has been silently weaving its influence. Mahila, or women.

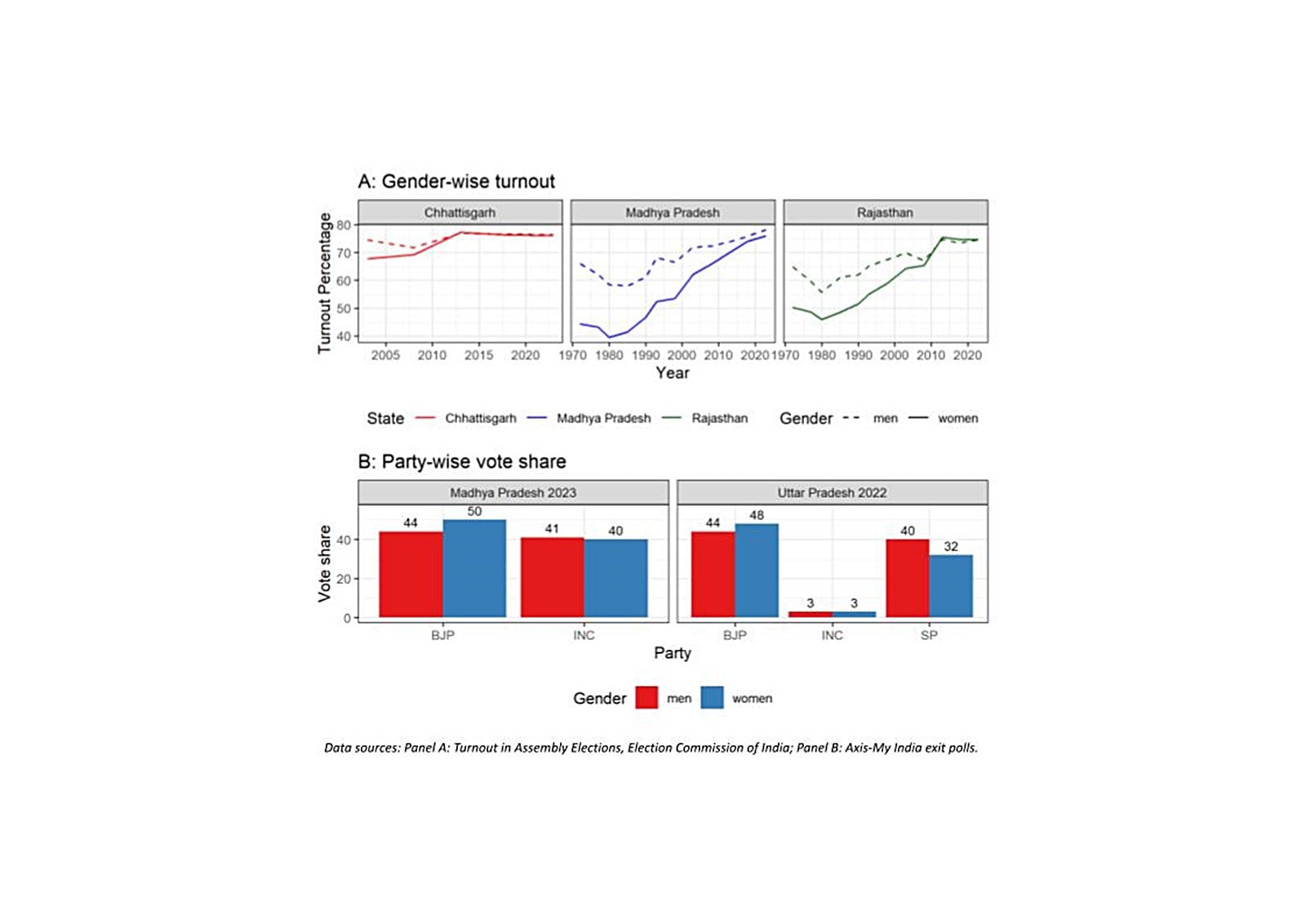

Across India, but notably in the “Hindi heartland,” women are voting in higher numbers, gradually bridging the gender gap in the voter turnout. This surge has not gone unnoticed, with parties making concerted efforts to woo this new electorate. But not all parties have been equally successful. Intriguingly, the BJP has seemingly shed its traditional image embodying a muscular and masculine form of Hindu nationalism to gain a significant edge among women voters. Indeed, exit polls conducted by Axis My-India show that the party had a remarkable 7 and 12 percentage point gender advantage over its closest competitors in Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh respectively.

Across India, but notably in the “Hindi heartland,” women are voting in higher numbers, gradually bridging the gender gap in the voter turnout.

Across India, but notably in the “Hindi heartland,” women are voting in higher numbers, gradually bridging the gender gap in the voter turnout.

The BJP’s success story among women is not confined to the ballot box. It extends to active participation in electoral events, rallies, and engagement between elections with survey data documenting a substantial increase in women’s active involvement with the BJP. So, what sets the BJP apart in its appeal to women voters and activists?

Prevailing explanations primarily centre on campaign promises and new welfarism involving public expenditure on private goods. The Ujjwala cooking gas subsidy set the template for this strategy, creating a new constituency of women beneficiaries or labharthis. Yet, as Praveen Chakravarty argued previously, neither are campaign promises always effective nor is credible delivery. In fact, political science research highlights some inherent limitations of campaigns in mobilising and persuading voters. One reason for this is that parties frequently adopt similar promises, diminishing the uniqueness of the original pledge.

This is not to say that campaigns are ineffective — just that attributing success (or failure) solely to a campaign runs the risk of occluding the incremental work parties and grassroots organisations do in between elections. In my research in Rajasthan over the last five years, I found marked differences in the mobilisation rhetoric deployed by political parties, their recruitment preferences, as well as the nature and frequency of their organisational activities.

In addition to conventional political tools, the BJP has strategically embraced the concept of seva or selfless service, as a central theme in its political narrative. This unique approach championed by Modi permeates the party’s messaging, events, and grassroots activities. From celebrating Seva Saptah/Pakhwara (Service Week/Fortnight) to naming Covid-relief programmes as Seva hi Sangathan (Organisation as Service), the BJP has embedded the concept of seva into its political fabric. This goes together with the party’s attempt to frame itself as a social service organisation interfacing between the state and society. For instance, in a letter lauding party workers’ Covid relief efforts in January 2021, J P Nadda noted how the BJP machine could be used as a tool of social service.

The emphasis on seva goes beyond political gestures; it trickles down to ground-level operations. Women’s wings, like the Mahila Morcha, are at the forefront of these activities, framing them as seva. From organising medical camps, blood donation and cleanliness drives, and tree plantation and wildlife conservation initiatives to religious and cultural celebrations, these activities are carefully aligned with local cultures and historical figures, aimed at creating an effective connection with communities, and helping draw women into its fold.

Crucially, these seva-based initiatives bridge the gap between traditional gender roles and women’s increasing involvement in politics. In a context that views party politics as “dirty” and not appropriate for women, framing political engagement as a form of service allows the BJP to render political participation acceptable to families that might otherwise be inimical to women’s transition into the public sphere. In doing so, the seva narrative aligns with traditional expectations of women as selfless and self-sacrificing, downplaying the potentially disruptive aspects of increased political agency. In a survey across three districts of Rajasthan, both women and men show greater inclination and acceptance of women’s partisan engagement when framed in terms of seva. This success can be attributed to seva embodying feminised traits that help portray politics as a positive extension of women’s domestic roles, binding the family and nation.

Although the use of seva may seem unique to the BJP, research by anthropologists Atreyee Sen and Tarini Bedi highlights parallels within the Shiv Sena, where women described their political activism as 80 per cent social work and 20 per cent politics. Crucially, nor does seva necessarily need to be a monopoly of conservative parties. Mahatma Gandhi, upon assuming stewardship of Congress in 1921, used remarkable political imagination to mobilise women into the hitherto male-dominated nationalist movement. Recognising the moral impetus women brought to social movements, Gandhi reframed women’s participation using the tools of seva to break the divide between the private and public spheres. By aligning the struggle for independence with seva-based ideals and programmes of swadeshi and ahimsa, Gandhi provided women — and as importantly their families — with a socially acceptable avenue for political engagement.

The history of women’s mobilisation then holds important lessons for understanding the present moment and women’s rising alignment and activism with the BJP. While campaigns and welfare schemes will continue to be important and visible means of enlisting the women’s vote, considering how political communication and organisational outreach can be used to overcome domestic barriers to women’s ability to enter the political sphere is critical not only for the prospects of political parties in 2024, but for larger questions of women’s political agency and representation in the future.

The writer is a Postdoctoral Fellow at Harvard University whose research examines how political parties mobilise women