Opinion What an artwork, a murder reveal

Part of the reason Cattelan’s Comedian has become a media sensation is because, in many ways, it’s a clever metaphor for our times: a zero-effort piece with zero aesthetic value, the Kim Kardashian version of art, famous and expensive for being ridiculous and nothing else.

Pushback against sanctioned stupidity and injustice takes time to become a movement. Maybe it requires a combination of bizarre situations like a six-million-dollar banana, tone-deaf celebrity dialogue alongside visibly vast inequality, and the shocking murder of a health insurance CEO to shake things up and effect change.

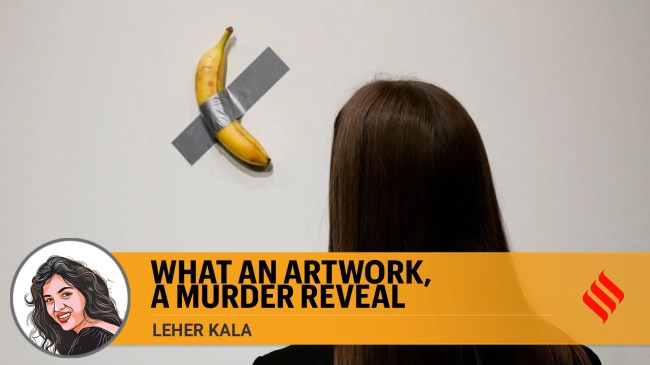

Pushback against sanctioned stupidity and injustice takes time to become a movement. Maybe it requires a combination of bizarre situations like a six-million-dollar banana, tone-deaf celebrity dialogue alongside visibly vast inequality, and the shocking murder of a health insurance CEO to shake things up and effect change. When the provocative artist Maurizio Cattelan first debuted his work Cattelan’s Comedian at Art Basel in 2019, the humble banana duct taped to the wall caused squealing laughter and spread much hilarity all around. Said banana artwork recently sold at Sotheby’s for $6.2 million. (Perhaps it’s entirely in keeping with this moment in history that a piece of gimmicky art was bought by a new-age cryptocurrency millionaire who proceeded to eat it onstage saying, “the real value is the concept itself”.)

And indeed, it is. If art is born out of a struggle with the hard facts of life, Cattelan’s Comedian subversively raises some profound questions. How does an object acquire its value in the art market? Who decides? Many of us novices find the business of viewing and ascribing beauty to artistic creations confusing. Why this and not that? At one end, there’s an uneasy feeling of inferiority that comes from lurking in a museum and simply not getting it, and on the other, there’s the sneaking suspicion that all contemporary art may be a hoax pulled on us by a tiny circle of pedigree and privilege. As a commentary on the art world, Cattelan’s deliberate absurdity pokes fun at the in-crowd that doles out millions for anything that has snob value. Truly, Cattelan has cast himself as the living embodiment of Andy Warhol’s words, that art is whatever you can get away with.

Part of the reason Cattelan’s Comedian has become a media sensation is because, in many ways, it’s a clever metaphor for our times: a zero-effort piece with zero aesthetic value, the Kim Kardashian version of art, famous and expensive for being ridiculous and nothing else. It reflects our post-truth world where style trumps substance and brings to mind cynical Orwellian thought — that who controls the present controls the past. Yet, it’s becoming harder to reconcile the splashy excesses of a lucky few gilded lives with images emerging from Gaza and Syria, where just existing is precariously fraught. Somewhere within, deep disillusionment with fly-by-night stars and greedy capitalists — influencers, reality TV stars, their trivial banalities and inane conversation — is beginning to creep in. It’s no coincidence that the Oxford Word of the Year is “brain rot” that translates to the deterioration of a person’s intellectual state from overconsumption of mindless content. In a sense, “brain rot” is a sobering warning to guard against disinformation and reclaim our minds.

Pushback against sanctioned stupidity and injustice takes time to become a movement. Maybe it requires a combination of bizarre situations like a six-million-dollar banana, tone-deaf celebrity dialogue alongside visibly vast inequality, and the shocking murder of a health insurance CEO to shake things up and effect change. Educated people from every social strata are openly and gleefully holding forth saying a millionaire boss got what he deserved, for being the reason that innocents are forced to run helter skelter to collect their own money. Can violence ever be justified? It is worth remembering that in one fell swoop, the French Revolution ended feudalism by beheading the entire nobility. Judging by stories coming out that CEOs in America are beefing up their personal security, they’re thinking of Marie Antoinette too.

Truth is not just stranger than fiction, sometimes they run parallel, together. The alleged murderer, Luigi Mangione, is eerily reminiscent of Dostoevsky’s character Raskolnikov from his masterpiece, Crime and Punishment. The starving anti-hero living in penury brutally stabs a cruel pawnbroker, who tortured her poor relative and other debtors, mercilessly. Reserved and introverted, Raskolnikov, much like Mangione, had vicious contempt for somebody who revered profit while remaining indifferent to people’s tragedies. The reader can’t help but feel sympathy for the despairing protagonist, much like people are feeling for young Mangione, whose shattering act has sparked off fresh debates on the nuances within “right” and “wrong”.

The writer is director, Hutkay Films