Opinion Uttarakhand UCC reflects a casual disdain for individual choice and liberty

The entire Uttarakhand UCC exercise seems to have been done only to show that it can be done, not that anything good can necessarily come out of it

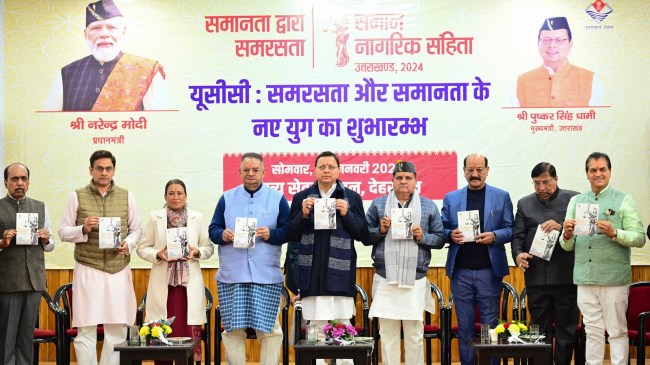

Uttarakhand Chief Minister Pushkar Singh Dhami launches Uniform Civil Code portal and a booklet, in Dehradun. (Source: PTI)

Uttarakhand Chief Minister Pushkar Singh Dhami launches Uniform Civil Code portal and a booklet, in Dehradun. (Source: PTI) For the longest time, the debate over a Uniform Civil Code (UCC) had one fundamental problem — no one had any clue what it was supposed to look like. All arguments for and against it were made on conflicting assumptions of what a UCC (mentioned in Article 44 of the Constitution) was supposed to be. Given this confusion, the arguments boiled down to this: Uniformity is per se good or uniformity is per se bad.

With Uttarakhand having passed its version of a UCC, we finally have at least some idea of what proponents of a UCC think it should be. Uniformity, it seems, is simply a way of creating a hodgepodge law that unthinkingly pastes provisions from different legislations into one “code” and then imposes oppressive, unconstitutional enforcement mechanisms on them. But even this uniformity is uniform only for some and not others. Scheduled Tribe communities have been kept out of the UCC (for good reasons which also apply to other communities).

The entire Uttarakhand UCC exercise seems to have been done only to show that it can be done, not that anything good can necessarily come out of it. It seems to only be about imposing Anglo-Hindu law in the interest of “uniformity” on communities that have never followed the same. The Uttarakhand UCC is of questionable constitutionality in multiple ways but I’ll highlight two crucial ones: extra-territoriality and invasion of privacy.

Extra-territoriality

Under Article 245 of the Constitution, laws made by a state legislature extend only to the territory of the state. Sub-section (3) of Section 1 of the Uttarakhand UCC contains one of the most bizarre statements in any law: “[the UCC] applies to the residents of Uttarakhand who resides [sic] outside the territories to which this Code extends to”. The absurdity is writ large. The most obvious question that arises: How is someone simultaneously a resident of Uttarakhand when they no longer reside in the state of Uttarakhand?

The provision is the result of the mindless copying of sub-section (2) of Section 1 of the Hindu Marriage Act, 1955 which extends Hindu law to Hindus who are not domiciled in India. It is a recognition of the principle that one carries one’s customary law (relating to marriage and divorce) with them even when they cross international borders. A similar provision does not exist in the Hindu Succession Act, 1956 for the obvious reason that it relates to property located in India and cannot apply to a Hindu who has property in another country.

However, the Uttarakhand UCC which contains provisions relating to both marriage and divorce and succession to property, mindlessly extends the Code to any “resident of Uttarakhand” whether or not they are actually a resident of Uttarakhand.

There is one circumstance where state laws can apply extraterritorially — if they relate to something having a “nexus” to the state. Given that there is no concept of dual citizenship in India, it is constitutionally dubious for Uttarakhand to extend its laws to individuals on the basis that they have some tangible connection to Uttarakhand even if they are not actually within the territory of Uttarakhand. In effect, Uttarakhand is asserting power over the personal lives of anyone who has any connection to the state no matter where they live.

This brings us to the most serious problem with the Uttarakhand UCC: Its intrusion on individual choice.

Intrusion on the right to privacy

The Uttarakhand UCC, like many other laws in other states, mandates registration of marriages on the pain of a civil penalty of Rs 10000. However, where the Uttarakhand UCC goes above and beyond is mandating that even people in a “live-in relationship” must be registered with the state. Failure to register a live-in relationship would entail criminal consequences of imprisonment and a fine.

There is no obvious benefit to registering a live-in relationship with the state government. It guarantees no legal rights to either partner. It offers no protections either. It is simply the state demanding that you reveal your private lives to them for the “record”, and such a record will be made public for anyone to inspect.

Mandating that anyone in a live-in relationship register with the government so that its curiosity is satisfied is a clear breach of the right to privacy guaranteed by Article 21. As a nine-judge bench of the Supreme Court has clarified in the Justice Puttaswamy case — the right to privacy includes the right to informational privacy and decisional autonomy. To demand that anyone who chooses to live with someone they love have to tell the state about the pain of criminal sanction violates both aspects of the right to privacy.

This is a country where inter-caste and inter-religious relationships are not just frowned upon but actively result in violent killings of the couple. Whatever its intentions, the Uttarakhand UCC reflects a casual disdain for individual choice and liberty.

The unconstitutional aspects of the UCC aside, one cannot but ask: Is uniform for its own sake any good if all it does is oppress everyone?

The writer is a co-founder of the Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy. Views are personal