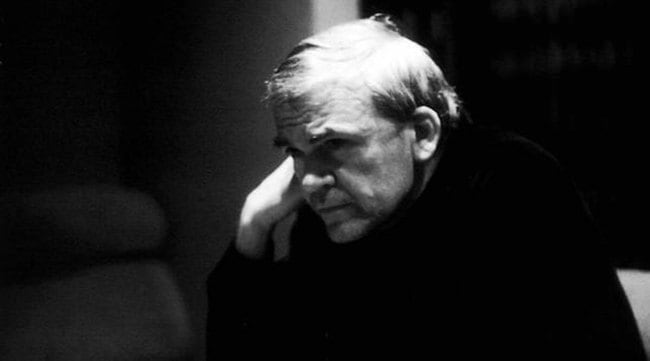

Opinion Pratap Bhanu Mehta writes: The Unbearable Lightness of Milan Kundera (1929-2023)

The voice of both the great and barbaric threat to freedom as well as of the void that freedom creates, Milan Kundera was a political novelist in the deepest sense of the term

Kundera is, at one level, a writer for our moment because he speaks at two levels. His original fame rested on diagnosing the totalitarian state as a form of illness — that puts the very possibility of human meaning at risk that erases all sense of the self. (Wikimedia Commons)

Kundera is, at one level, a writer for our moment because he speaks at two levels. His original fame rested on diagnosing the totalitarian state as a form of illness — that puts the very possibility of human meaning at risk that erases all sense of the self. (Wikimedia Commons) A few weeks ago, I happened to be browsing through Milan Kundera’s last book, A Kidnapped West: The Tragedy of Central Europe, published this year. In a way, this is a fitting last book for him to publish. It underscores the one abiding theme of his politically eventful and gloriously creative literary life: a perpetual sense of disappointment and disillusion. Kundera’s inventive and brilliant, The Unbearable Lightness of Being (1984) was one of the most effective critiques of communism because it focussed both on its repression and the sheer sense of meaninglessness it created. But the existential import of the novel was far more ambiguous in at least two ways. The main character, Tomas, removes himself from politics, paradoxically through a political act of a refusal to cooperate with the regime, and ends up searching for meaning in the life of private passion. But the novel also leaves it ambiguous whether it was better to die under the “sign of weight”, where the search for meaning was still possible, or under a sense of “lightness”, where one literally lives in the moment, as it were; even the future is a burden to be avoided. The world of communism, it turned out, was a charnel house of meaning, and rotting ideals. But the literary achievement of The Unbearable Lightness… was to convey so heavy a claim, in the lightest manner possible. His works (Life is Elsewhere, 1973; The Book of Laughter and Forgetting, 1978; Immortality, 1988) are often described as “black comedies.” But in a way they were far more radical, because you were never sure at whose expense the joke was.

But, in retrospect, his work turns out, was not just an indictment of communism but of existence. He was admirably disillusioned. Unlike many other gifted critics of communism, he refused to settle for an easy and shallow liberalism. So much of his literary power derived from one of his great fears: the erasure of Czech national memory (and the memory of small nations), the carpet bombing of culture and the rewriting of history that communism represented. And yet, he dissociated himself from Czech culture, even forbidding translations of his work into that language and refusing honour from that other hero of the Sixties — Vaclav Havel — as if it was his bounden duty to declare that culture dead. He had started his life as a communist, and could see the dream of paradise that lay behind it. But, as he once put it, in an interview to Philip Roth, “once the dream of paradise starts to turn into reality however, here and there people crop up who stand in its way, and so the rulers of paradise must build a Gulag on the side of Eden. In the course of time, this Gulag grows ever bigger and more perfect, while the adjoining paradise gets smaller and poorer.” But in turn, almost every ideal — modernity, the nation, progressive humanism, consumer culture, even culture – Kundera seemed to suggest comes with the temptation of its own Gulag.

It is, therefore, a supreme irony that this great writer who was considered a political novelist in the deepest sense of the term, like his character Tomas, ends up seeking refuge outside the world of ordinary politics. The power of his politics comes from the clarity with which he sees the ethical irrationality of acting in the world, especially in the name of some act of collective meaning making. There is almost a paranoid suspicion of our ability to make a world of meaning together in common. It is almost as if any action is already in the grip of a delirium. I think fundamentally he was paranoid about power, corrupting that thing called culture and moral sense. As he put it “true human goodness, in all its purity and freedom, can come to the fore only when its recipient has no power.” He had said this in the context of human treatment of animals, for him the true debacle of civilization, where mankind fails the test of treating kindly those at its mercy. But you can see the general thought running through his anxiety about political action. What you make of Kundera depends on whether you see this as a counsel of despair of a cautionary tale.

Kundera is, at one level, a writer for our moment because he speaks at two levels. His original fame rested on diagnosing the totalitarian state as a form of illness — that puts the very possibility of human meaning at risk that erases all sense of the self. And yet, even the threat of the hangman is lifted, what we create is a zone of arid meaninglessness. He becomes the voice of both the great and barbaric threat to freedom, but also the void that freedom creates. He is clairvoyant precisely because he offers no consolation. Perhaps the only refuge from this void was mirth, which his writing gave in ample measure.

Pratap Bhanu Mehta is contributing editor, The Indian Express