Opinion Tavleen Singh on why SC should act against those using bulldozers to deliver justice

Unfortunately, the Justice Varma case has not become a reason for some serious attempts at judicial reform

When I saw that the Prayagraj demolition victims had managed to be heard in the Supreme Court, I found myself wondering how they had succeeded and with whose help.

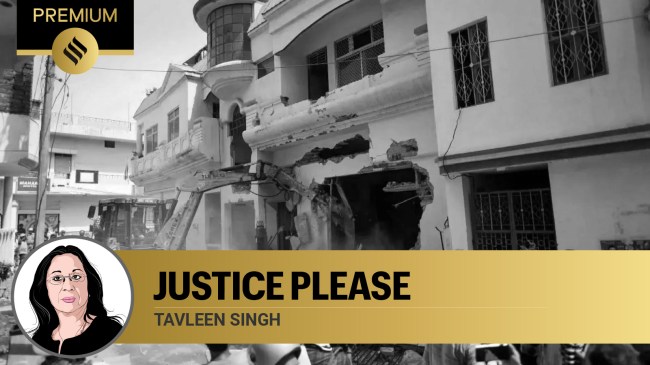

When I saw that the Prayagraj demolition victims had managed to be heard in the Supreme Court, I found myself wondering how they had succeeded and with whose help. On the front page of this newspaper last week appeared the picture of a little girl clutching her schoolbooks in her hand to save them from the bulldozers that were demolishing her home. A picture, as the old journalism cliché goes, is worth a thousand words. So I found it hard to look at this picture, and not feel shame and sorrow. And anger that the Chief Minister of Uttar Pradesh, who likes being called Bulldozer Baba, believes that what he is doing is delivering justice. It was this picture that shook the conscience of the Supreme Court, and it ruled last week that this kind of demolition of people’s homes was ‘inhuman and illegal’. The right to shelter is ‘an integral part of Article 21 of the Constitution of India’.

The Supreme Court has ruled against ‘bulldozer justice’ before, but this time it ordered the Prayagraj municipality to pay compensation of Rs 10 lakh to each of the people whose homes had been demolished. As recompense it is no more than tokenism, but the Supreme Court has at least asserted once more that justice by bulldozing people’s homes is not justice at all. This newspaper has so far been the only one to make the effort to go to Prayagraj and talk to the people who lost their homes without being given time to take out their most treasured possessions. A professor whose home was demolished while he was travelling said it broke his heart when he saw that his library of more than a thousand books had been destroyed.

The Supreme Court’s judgment has restored some faith in the judiciary. Faith that has eroded rapidly since that roomful of half-burned Rs 500 notes was discovered in the home of Justice Yashwant Varma. But much more needs to happen for faith in the rule of law to be fully restored. The stash found at Justice Varma’s residence has led to long articles on the justice system and passionate debates on television, but they have been entirely confined to discussing how judges should be appointed to our higher courts.

A lawyer friend who appeared in one of these debates said to me later that the problem lies much lower down the line in the courts that the ‘common man’ must deal with. I agree. As someone who has tried to help street people in Mumbai who have been arrested for vagrancy, I have some experience of dealing with these lower courts. It is not a happy experience. In my case, I was appalled at the filthy corridors I wended my way through to dusty courtrooms. And more appalled when a lawyer charged me a small fortune to help get bail for these homeless people.

The ‘common man’ does not go to court unless it is essential because not only can he not afford to pay lawyers’ fees, but he cannot wait for years, sometimes decades, for justice to be done. Cases of terrorism, murder, drug trafficking and rape usually languish in our courts for so long that by the time justice is done, the victims are forgotten as well as the crime. It is because of this that the consensus on social media (the new public square) is that chief ministers who order bulldozers to demolish the homes of suspected criminals are doing the right thing. The people who lost their homes in Prayagraj did so because Yogi Adityanath believed that these homes were on land belonging to a gangster. It is impossible to convince someone who enjoys the sobriquet ‘Bulldozer Baba’ that even gangsters should have the right to a trial in a court of law.

After the stash was discovered at the judge’s residence, I have found it difficult to say anything good about a Supreme Court judgment without being reminded of corruption in the judiciary. It is unfortunate that the Justice Varma case has not become a reason for some serious attempt at judicial reform. Unfortunate that when the word reform is mentioned the only discussion that takes place is about the appointment of higher judges.

Almost never has there been a serious effort to improve the lackadaisical way the justice system functions, and the endless delays that cause ordinary Indians to lose faith and hope in the rule of law. At the lower levels of the judiciary, I have seen courts in which dogs and cows wander and judges sitting surrounded by heaps of crumbling files. Hardly the atmosphere in which you can begin to discuss the ‘majesty’ of justice. So, there are problems. Big problems. But the solution is not to replace the rule of law with the law of the jungle as BJP chief ministers have taken to doing.

When I saw that the Prayagraj demolition victims had managed to be heard in the Supreme Court, I found myself wondering how they had succeeded and with whose help. It has taken them nearly five years to get justice and they will probably never manage to find enough money again to rebuild the homes they lost, but that they got to the Supreme Court is a miracle. Nothing is more important than getting the Indian justice system to work more efficiently than it does and to become affordable for ordinary Indians.

Meanwhile, the Supreme Court would do India a huge service if it acted against chief ministers who continue to use bulldozers to deliver justice. What about at least contempt charges?